Pottery shards found at the ancient settlement were analyzed for fragments of organic residue and protein. The culinary habits of the ancient Maltese were determined from the results of this analysis.

The Times of Malta reported that researchers led by Davide Tanasi of the University of South Florida analyzed residual proteins and traces found in pottery. The history of these proteins can be traced back to between 2500 and 700 BC. between.

Il-Qlejgha tal-Bahrija, a prehistoric site located in the northern region of Malta. Studies have shown that residents of Il-Qlejgha tal-Bahrija eat porridge made from milk and grains such as wheat and barley.

The organic residues and protein fragments in the pottery fragments found in ancient settlements were analyzed. This allowed researchers to determine certain ingredients that formed part of the Maltese Bronze Age diet.

This research is part of the Mediterranean Diet Archaeology project, led by Davide Tanasi of the Advanced Institute of Culture and Environment at the University of South Florida.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

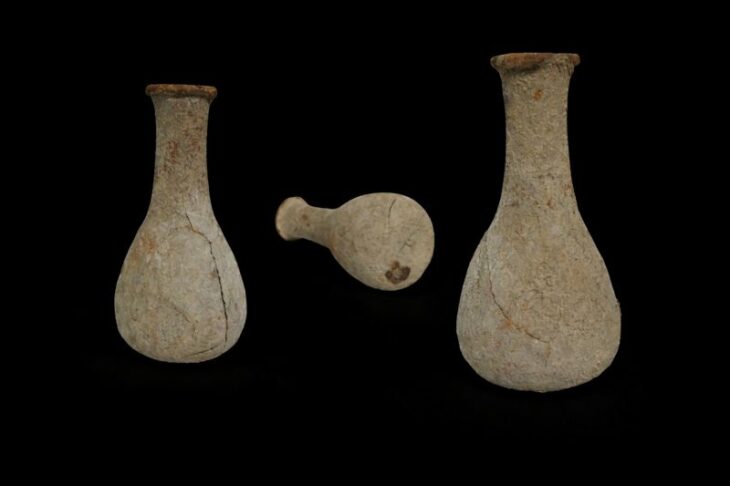

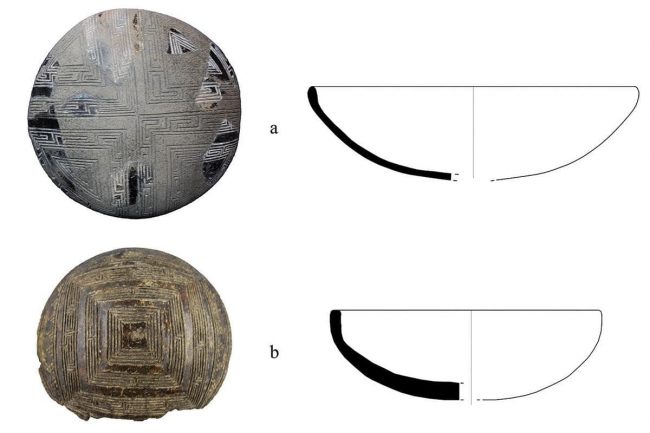

The shapes of different types of pottery were analyzed to determine the traditional functions of these vessels, and an attempt was made to reconstruct the eating habits, food processing practices, and agricultural-related economic strategies of the indigenous communities of Malta.

“Food, cuisine and diet in the past was traditionally neglected and studies would focus on other aspects for the simple fact that it was hard to get information. It’s invisible and the visible remains are tiny and microscopic,” Tanasi told Times of Malta.

“But thanks to innovative technology, it is now important to discover these aspects of the past. How can we know the ancient inhabitants if we don’t try to understand what their diet was based on and how they generated their essential nutrients?”

The analysis revealed that the containers carried a mixture of bovine milk and cereals that suggested the presence of a prehistoric porridge.

The vast majority of storage jars show many proteins compatible with wheat, while others also contain protein, indicating that the container has been used to store barley.

The data, Tanasi said, indicated that the Maltese of Il-Qlejgħa tal-Baħrija had a culture of bovine farming and milk processing.

The presence of large storage jars, now known to contain cereals, also suggested a system of accumulation and redistribution of agricultural surplus, a practice that has been observed at similar sites in Sicily.

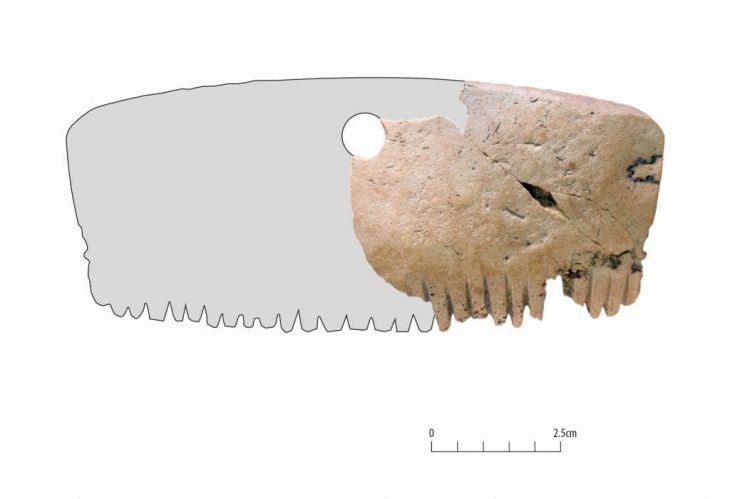

By examining pottery fragments, Tanasi and his team were also able to determine that pottery vessels previously interpreted as incense, shaped like a wicker basket with gaps, contained cow’s milk particles.

This indicates that the container was used in early cheese production, similar to the lattice basket used to make ricotta cheese. Tanasi said this discovery is very important because there has been no other evidence of cattle farms and milk processing, such as animal bones.

The scientific analysis was conducted at the Laboratory of Organic Mass Spectrometry of the University of Catania’s Department of Chemical Sciences (Italy) in partnership with the Institut de Chimie Radicalaire of Aix-Marseille Université (France).

In the statements he made, the researcher also mentioned the difficulties he faced.

Tanasi said the process of re-contextualizing the site was difficult, partly because of having to work with older data that had been stored and processed many times by others over the past century, and also because of the need to work with ancient proteins.