What started as a pile of broken plaster fragments has become one of the most remarkable reconstruction projects in British archaeology. At a site in Southwark, where development firm Landsec is preparing the ground for the ‘Liberty’ project, archaeologists uncovered what appeared to be demolition waste from a Roman building—shattered pieces of painted plaster, forgotten for nearly 2,000 years.

It wasn’t until Senior Building Material Specialist Han Li from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) began the painstaking process of sorting and reassembling the pieces that the true significance of the discovery came to light: a massive collection of Roman frescoes, carefully reconstructed from thousands of jumbled fragments.

Reassembling the Roman Past, One Fragile Piece at a Time

“This has been a once-in-a-lifetime moment,” said Han Li, who has spent months methodically examining and aligning each piece. “It was like solving the world’s most difficult jigsaw puzzle—with no box, missing edges, and pieces from multiple images mixed together.”

Originally dumped in a large pit during Roman demolition works around AD 200, the fragments were a chaotic mix from at least 20 walls of a once-grand Roman building. Their painted surfaces were so delicate that every attempt to fit two pieces together carried the risk of irreversible damage.

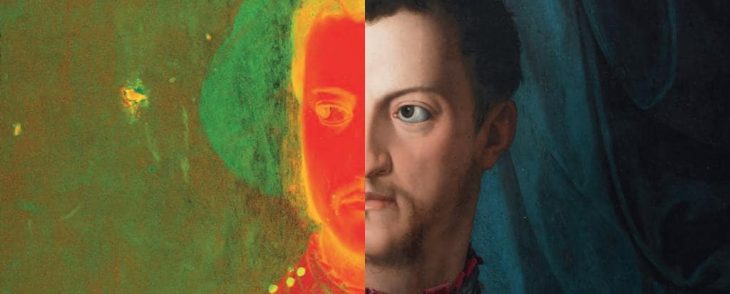

To minimize error, Li and the team employed advanced lighting techniques and digital mapping, relying on minute details—paint texture, brush strokes, and pigment types—to guide their reconstructions. Only then did shapes and figures begin to reemerge: vivid yellow panels, elegant candelabras, white birds, fruit, and stringed instruments known as lyres.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

A Hidden Artist’s Mark and Graffiti from Antiquity

As the puzzle came together, surprises emerged. Among the fragments was a tabula ansata, a decorative Roman frame, containing the Latin word FECIT—“has made this”—marking what is believed to be the first known artist’s signature ever discovered in Roman Britain. Unfortunately, the piece with the artist’s actual name is still missing.

Other plaster pieces featured ancient graffiti, including the only known example of the Greek alphabet etched in plaster in Britain, likely used as a practical reference by someone familiar with writing. One fragment even shows a sketch of a crying woman, possibly dating to the Flavian dynasty, while another reveals the geometric guidelines for a flower design that was never painted.

“These faint lines and inscriptions offer an intimate look into the process,” said Li. “They’re not just artwork; they’re evidence of thought, hesitation, revision. They humanize the ancient world.”

Not Just an Artifact—A Masterclass in Reconstruction

While Roman wall paintings have been found across Europe, the scale and reconstruction of this assemblage set it apart. The largest fresco, nearly 5 meters wide, was rebuilt from pieces no bigger than a human palm. Much like digital forensics, this effort required a blend of craftsmanship, science, and artistic intuition.

“This wasn’t just about finding history—it was about restoring it,” said Faith Vardy, MOLA’s senior illustrator, who helped digitally visualize the scenes as they came together.

Preserving the Process for Future Generations

Work on the fragments is ongoing, and the team plans to publish a detailed reconstruction report. The restored frescoes may also be made available for public exhibition. The project is part of a broader excavation at the Liberty site, supported by Landsec, Transport for London (TfL), and Southwark Council.

As more pieces are carefully analyzed and assembled, the project serves as a rare reminder that archaeology is not just about what we find—but how we rebuild the past from what remains.

Museum of London Archaeology (Mola)

Cover Image Credit: Museum of London Archaeology (Mola)