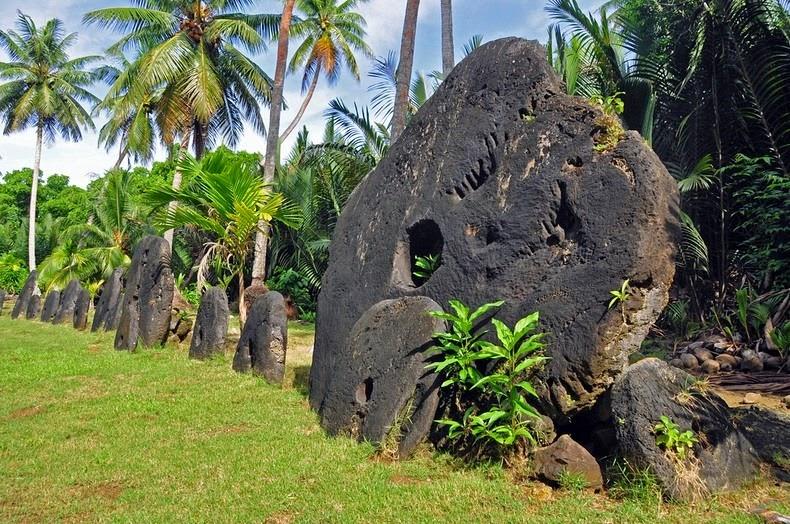

Human civilizations tend to assign monetary worth to goods based on scarcity, among other factors. This is unquestionably true in the case of Yap’s massive money stones. On the island of Yap, there is no limestone, so imagine the effort required to move a 9000-pound stone “coin” over hundreds of miles of open ocean in canoes and rafts.

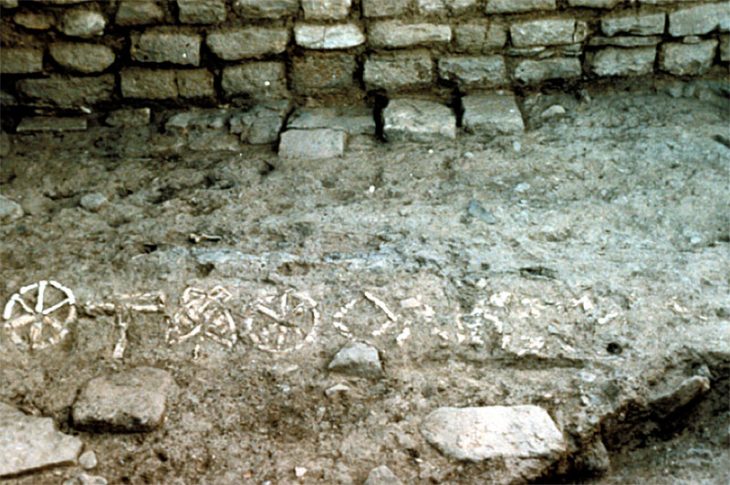

The stone circles are carved from limestone slabs and can be as large as 4 meters (12 feet) in diameter, however, they range in size from an Oreo to a cartwheel or a truck.

According to local, about 500 to 600 years ago, a man named Ana Gumang led an expedition from his hometown of Yap Island to the remote island of Palau 300 miles away. The Yap people were immediately fascinated by Palau’s rich limestone resources. The indigenous people of Palau allowed the people of Yap to mine the rock in exchange for goods and services, establishing a remarkable economic exchange between the two islands. Though initially new, these stones quickly took over as the actual currency on Yap. First, the stones were carved into fish shapes, but later a slightly more practical disc shape was adopted. The stone remained the main currency until the 20th century.

Like a huge coin, Rai stone is exchanged as a symbol of value in ceremonies of important cultural significance (such as marriage, inheritance, conflict resolution, or political transactions). Although cash is usually used in daily life on the island, Rai stone is still used for ceremonial exchanges today.

The knowledge about who owns what is recorded in the public oral tradition, the transfer of gems is carried out in public ceremonies, and everyone can see it.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Archaeologists and economists from the University of Oregon researched this money system in 2019 and concluded that it resembles cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin.

Key among those parallels: Both bitcoin and rai allow people to own and use money without physically possessing it, and both systems accomplish this through a community ledger system that ensures transparency and security without the help of a centralized bank.

“As with the rai stones, information about bitcoins’ value and ownership is managed collectively; it’s a distributed financial system as opposed to the more familiar, centralized systems involving third-party financial institutions,” Stephen McKeon, an associate professor in the Department of Finance at the University of Oregon, who worked on the project, said in a statement.

“History often repeats itself, and this is a case in point. It’s reasonable to infer that the Yapese model was the impetus for a digital means of doing something very similar,” added Scott Fitzpatrick, an archaeologist who led to study. “Either that, or it’s a case of cultural convergent evolution, where two temporally and geographically distinct cultures develop a remarkably similar system, which would still be pretty intriguing.”

Fundamentally, the rai stones demonstrate how ephemeral and enigmatic the concept of cash is. Anything that is utilized as a medium of exchange for goods and services is referred to as currency. Nations in the twenty-first century employ fiat money, which has no inherent value (you can’t eat or wear a banknote) and isn’t linked to the price of any precious metal, such as gold. In reality, it’s all just abstract.

Our money only has worth because we’ve all decided it does, much like a gigantic stone in the Micronesian forest or a bag of old beads.

Source: University of Oregon