Archaeologists discovered a brick inscribed with Akkadian script, marking the Elamite water supply system, alongside some intricately patterned bricks in Iran’s Dehloran Valley.

This discovery sheds light on the political and economic significance of the ancient site of Garan, located on the western border of Elamite civilization.

According to ISNA, the findings were reported during a specialized session titled “Representation of Dehloran Valley’s Perspective; Based on the Discoveries of Garan Mound,” organized by the Institute of Archaeology.

Tappeh Gārān (locally pronounced Gharrān) is a large mound in the Deh Luran plain, about 3 km east of the Dawairij River and 2.8 km north/northwestern of Tappeh Musiyan.

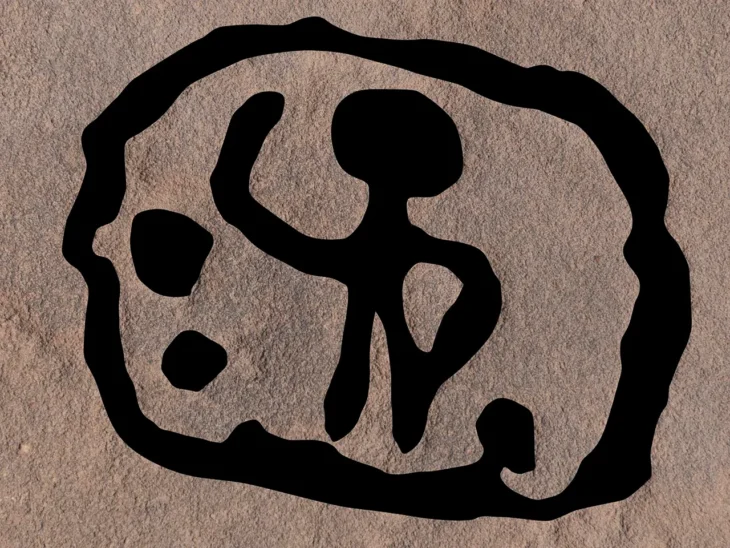

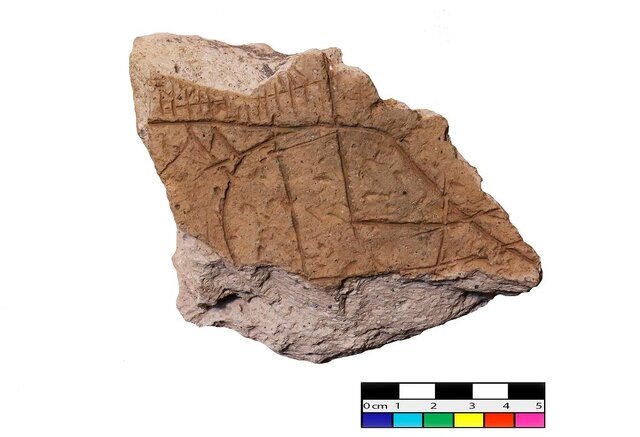

Researchers believe that the written objects found at Gārān consist of Akkadian scripts and geometric patterns thought to illustrate the outlines of an agricultural scheme.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Frank Hole, Kent Flannery, James Neely, and Henry Wright conducted historic archaeological work in the Deh Luran plain in southwest Iran nearly 50 years ago. In 2016 and 2019, the area was resurveyed to determine whether agricultural and increased irrigation activities had destroyed any archaeological sites.

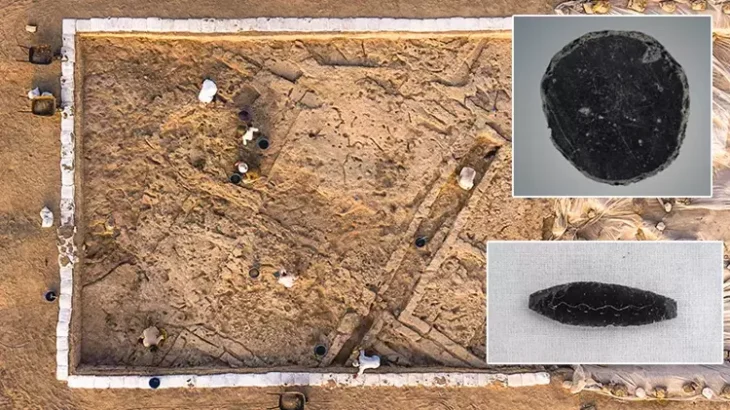

During the surface survey on Gārān Mound two inscribed objects were found. The inscriptions yield some information on the economic and political importance of Tappeh Gārān in the Old Elamite Period.

“Garan, situated in the Dehloran Valley within the modern province of Ilam and on the southwestern plateau of Iran, covers an area of 17 hectares. It features a prominent cone-shaped elevation in the south of the site, surrounded by several irregular mounds to the east, north, and west of the main prominence,” said Mohsen Zeinivand, an archaeologist involved in the excavation.

Zeinivand highlighted the exceptional importance of Garan in archaeological studies of the region due to its organized human habitation sequence from the late ancient periods to the end of the historical era.

It transformed into the largest settlement in the second millennium BC until the late Achaemenid period, holding extraordinary significance in the archaeology of the area, the archaeologist said.

Regarding recent examinations of the site, Zeinivand explained: “Surface surveys identified numerous broken bricks with possible inscriptions. Although the inscriptions on these brick fragments were not easily decipherable due to weathering and erosion, one sample revealed partially readable words such as ‘ruler,’ ‘son,’ and ‘his lord,’ suggesting Akkadian language.”

According to Zeinivand, the lines on the patterned bricks represent four distinct features: a river, a mountain, a dam or embankment, and irrigation channels.

In conclusion, the archaeologist emphasized that the Akkadian-inscribed brick, coupled with the patterned ones, likely offers insights into the political and economic significance of Garan on the western borders of ancient Elam.

The name Elam was given to the region by others– the Akkadians and Sumerians of Mesopotamia–– and is thought to be their version of what the Elamites called themselves– Haltami (or Haltamti)– meaning “those of the high country.” ‘Elam’, therefore, is usually translated to mean“highlands” or “high country” as it comprised settlements on the Iranian Plateau that stretched from the southern plains to the elevations of the Zagros Mountains.

Susa was formerly the capital of the Elamite Empire and later an administrative capital of the king of Achaemenian, Darius I and his successors of 522 BC. Throughout the late prehistoric periods, Elam was closely tied culturally to Mesopotamia. Later, perhaps because of domination by the Akkadian dynasty (c. 2334–c. 2154 BC), the Elamites adopted the Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform script.