Archaeological excavations at Oluz Höyük in Amasya, north-central Türkiye, have revealed rare evidence of Phoenician presence deep inside Anatolia, including human-faced glass beads believed to have originated from Carthage and a group of baby burials placed inside ceramic jars. Researchers say the discovery is unlike anything previously documented in the region and may reflect cultural practices associated with the broader Phoenician world.

Oluz Höyük, where excavations began in 2007, preserves ten settlement layers spanning approximately 6,500 years of history. The site has already yielded architectural remains from the Hittite, Phrygian, and Persian periods, including palatial structures and sacred spaces. According to excavation director Prof. Dr. Şevket Dönmez of Istanbul University, the latest finds emerged from a temple precinct linked to the ancient Anatolian goddess Kubaba and reveal clear architectural parallels with Aramaean and Phoenician temples of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Phoenician Presence Reaches Central Anatolia

“The plan of the temple shows a long, narrow, megaroid layout that closely resembles Aramaean–Phoenician sanctuaries,” Dönmez explained. “Phoenicians were a Semitic people who lived along the Eastern Mediterranean coast and later spread their culture and trade networks across the Mediterranean. Finding their traces this far into Central Anatolia is truly remarkable.”

Among the most striking artifacts are small human-faced glass beads, stylistically linked to workshops associated with the Phoenician city-state of Carthage. Such beads, often interpreted as amulets, were traded widely in antiquity and are emblematic of Phoenician craftsmanship and maritime connectivity. Their presence at Oluz Höyük suggests that the site was part of long-distance exchange routes that once stretched from the Levant to North Africa and beyond.

Baby Burials in Ceramic Jars: A First for Anatolia

Even more extraordinary is the discovery of up to eight infant and fetus burials carefully placed in ceramic jars and arranged with deliberate spacing across the sacred area. “These baby jar burials do not resemble any burial practice previously documented in Anatolia,” Dönmez said. “Their form and placement are consistent with funerary traditions known from Phoenician contexts.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Jar burials for infants are attested at several Phoenician sites around the Mediterranean, where they have been interpreted in different ways by scholars—sometimes as funerary customs for children who died young, and in other cases as part of ritual practices linked to religious offerings. At Oluz Höyük, researchers emphasize that the exact meaning of the burials remains under investigation and will require careful anthropological analysis before firm conclusions can be reached.

Contextualizing Phoenician Child Burials

In the Phoenician world, certain sacred precincts—often referred to in scholarship as Tophet areas—have yielded cemeteries containing urns or jars associated with children and infants. While interpretations vary and remain debated, many researchers discuss these finds within the framework of ritual, memorial, or votive practices tied to local religious beliefs. The discoveries at Oluz Höyük may provide an Anatolian counterpart to these well-known Mediterranean examples, though the team stresses that any cultural parallels must be evaluated cautiously and scientifically.

“Our preliminary assessment is that the Oluz Höyük jars reflect a tradition familiar from Phoenician ritual spaces,” Dönmez noted. “Whether these children were ritually dedicated, or whether they died naturally and were buried according to a specific cultural practice, can only be clarified through interdisciplinary study.”

A Window into Trade, Religion, and Cultural Exchange

The finds deepen ongoing discussions about how Phoenician communities interacted with inland regions. Historically renowned as master sailors, traders, and artisans, the Phoenicians established networks that connected cities such as Tyre, Sidon, and Carthage with ports and trade centers across the Mediterranean basin. The presence of imported glass beads and culturally distinctive burials at Oluz Höyük suggests that these networks extended farther into Anatolia than previously confirmed.

Archaeologists also highlight the symbolic role of the human-faced glass beads. Often associated with protective or apotropaic meanings, these beads may have been carried as personal ornaments or ritual items. Their discovery alongside the jar burials raises important questions about belief systems, identity, and the movement of ideas as well as goods.

Preserving a Heritage Legacy

Excavations at Oluz Höyük continue under Türkiye’s “Heritage for the Future” initiative, supported by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Nearly 3,000 artifacts uncovered at the site have already been transferred to the Amasya Museum for conservation and display, ensuring that the discoveries will be accessible to researchers and the public.

As studies progress, the Oluz Höyük findings promise to play a key role in reassessing the cultural map of Iron Age Anatolia and the reach of Phoenician influence. By combining archaeological evidence, architectural analysis, and forthcoming anthropological research, scholars hope to better understand how trade, religion, and cultural exchange shaped life in this crossroads region—where, for the first time, baby jar burials with clear Phoenician connections have been documented in Anatolia.

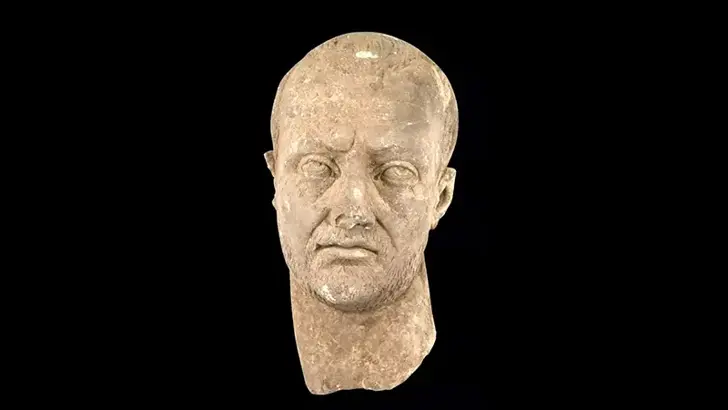

Cover Image Credit: İHA