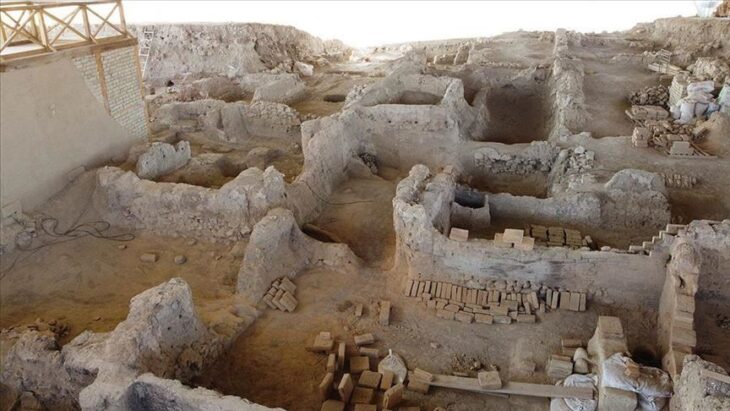

Goethe University archaeologists return with discoveries that reshape understanding of Christian–Zoroastrian life 1,500 years ago

A research team from Goethe University Frankfurt has returned from northern Iraq with groundbreaking insights into the religious landscape of Late Antiquity in the Middle East. After a three-year investigation at the archaeological site of Gird-î Kazhaw in Iraqi Kurdistan, archaeologists have uncovered evidence suggesting that Christians and Zoroastrians lived peacefully side by side around the 5th century CE—a period known for dramatic political changes across Western Asia.

Although the team did not unearth portable artifacts of high material value, the excavation produced something far more significant: a deeper understanding of daily life, architecture, and interreligious dynamics in a region often overlooked by mainstream archaeological research. The project was led by Dr. Alexander Tamm of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg and Professor Dirk Wicke of Goethe University’s Institute for Archaeological Sciences.

Their work focused on two areas: a suspected early Christian architectural complex and an Islamic-period cemetery built atop an earlier Sasanian fortification. Together, these layers of history offer a rare archaeological snapshot of cultural continuity across Christian, Zoroastrian, and Islamic communities.

A Mysterious 5th-Century Structure Revealed

One of the central goals of this year’s campaign was to determine the function of a previously discovered stone-pillared building, first documented in 2015. The structure, built around 500 CE, had long puzzled researchers. Five square pillars made of rubble stones and coated in white gypsum had initially prompted speculation that the site might represent an early Christian church. Geophysical surveys had hinted at additional walls underground, possibly forming part of a larger monastic complex.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

During the latest excavation season, the Frankfurt team opened a broad horizontal area—known as Area A—around the pillar building. Within a relatively shallow depth, they uncovered brick walls, compacted-earth floors, and later stone-and-brick floor surfaces. But the most striking discovery was a second set of stone pillars, suggesting the building featured a three-aisled plan with a long central nave. The orientation—northwest to southeast—matches what is known from early Christian architecture in northern Syria and Upper Mesopotamia.

One surprising detail is the unusual size of the main nave, estimated at 25 by 5 meters—not massive by cathedral standards, but significantly larger than typical rural religious structures in the region.

Another key feature emerged in the form of a room containing a finely laid brick floor and a semi-circular niche at its northeastern end. Such design elements are consistent with early Christian liturgical spaces, which often incorporated apses or rounded focal points for worship.

The architectural clues were reinforced by a small but meaningful artifact: a pottery sherd decorated with a Maltese cross. While a single motif is not conclusive in itself, combined with the structural evidence it strongly supports the interpretation of the building as an early Christian meeting place.

A Zoroastrian Neighbor? Rethinking Religious Boundaries

What makes the site especially valuable for historians of religion is its proximity to a small Sasanian-period fortification located directly adjacent to the Christian structure. The Sasanians, who ruled much of Iran and Iraq before the Islamic conquests, were predominantly Zoroastrian, following the teachings of the prophet Zarathustra (Zoroaster).

If both the Christian complex and the Sasanian fort date to the same period—as current findings tentatively suggest—they may represent direct archaeological evidence of coexistence between residents of the two communities. Such living arrangements are documented in historical sources but rarely preserved so clearly in the material record.

This discovery aligns closely with the goals of the newly approved LOEWE research center “Dynamics of the Religious”, launching in 2026. Scholars involved in the program aim to explore shifting religious identities and everyday interactions in multicultural regions across history.

The site also bears witness to a later shift in the region’s spiritual landscape. Over time, the Sasanian structure was overlain by an Islamic cemetery, excavated in Area B. The Frankfurt team focused on careful anthropological documentation of the graves, which reflect the gradual spread of Islam through northern Mesopotamia after the 7th century.

Rural Life Takes Center Stage

The Gird-î Kazhaw project belongs to a broader research initiative addressing rural settlement patterns in the Shahrizor Plain of northern Iraq. Historically, archaeological work in the Middle East has concentrated on great imperial capitals such as Nineveh, Babylon, and Ctesiphon. Tamm and Wicke argue that this emphasis neglects the essential economic and cultural role played by smaller villages and farming communities.

Their work highlights an important truth: while empires shape political history, ordinary people in rural landscapes sustain the economic foundations that allow cities to flourish.

The next stages of research will combine traditional excavation with archaeometric methods, including archaeobotany (the study of ancient plant remains), zooarchaeology (animal remains), and forensic anthropology. These techniques will help reconstruct how people used space, what they ate, how they built their homes, and how religious practices may have changed over generations.

A Window into a Shared Past

For archaeologists and historians alike, the findings at Gird-î Kazhaw offer a rare and compelling look at interreligious interaction outside major urban centers. Rather than depicting ancient Iraq as a landscape of conflict, the new evidence paints a more nuanced picture—one where Christian, Zoroastrian, and later Islamic communities lived in relative proximity, adapted to one another, and built overlapping histories still visible in the soil today.

Cover Image Credit: Gird-î Kazhaw. Dirk Wicke