Hidden for more than 3,000 years in the lowlands of Tabasco, the vast lost Maya ritual complex of Aguada Fénix is rewriting the story of early civilization—showing that the first great monuments of Mesoamerica were built without kings.

In a groundbreaking revelation, archaeologists from the University of Arizona have unearthed new evidence that reshapes the understanding of early Mesoamerican civilization. Led by Regents Professor Takeshi Inomata and Fred A. Reicker Distinguished Professor Daniela Triadan, the team has discovered a massive landscape-wide ceremonial complex at Aguada Fénix, a site in southeastern Mexico’s Tabasco state. Their findings, published in Science Advances on November 5, 2025, reveal the earliest and largest known cosmogram—a symbolic model of the universe—constructed by early Maya-related communities around 1050–700 BCE.

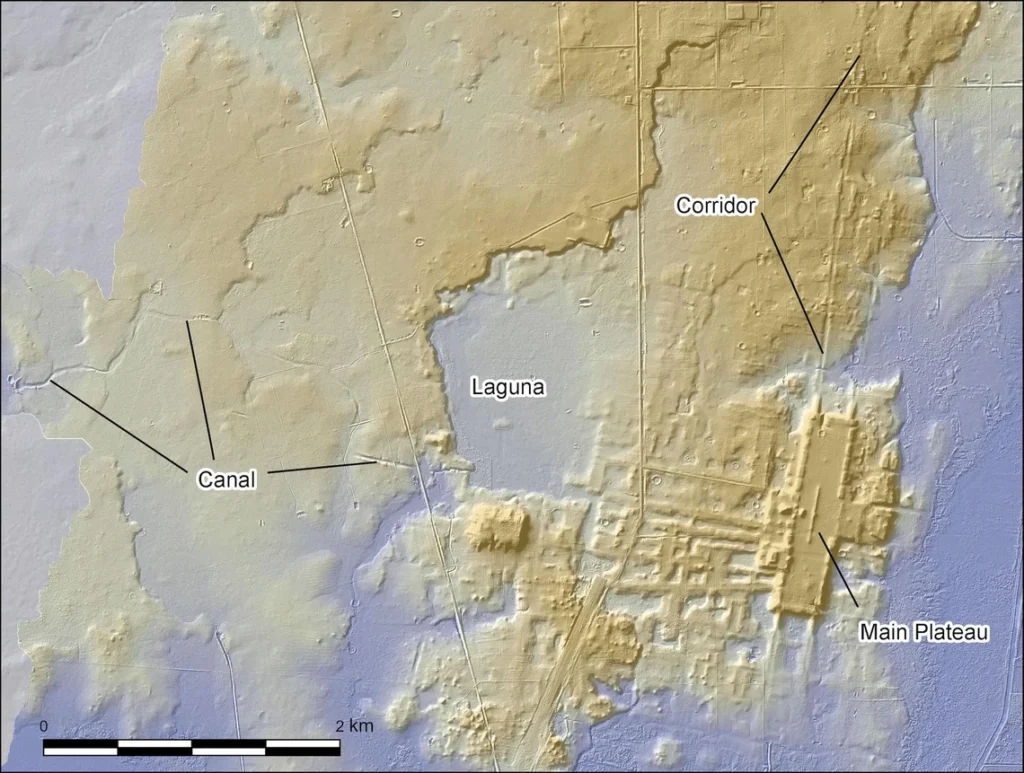

The discovery builds upon the 2020 identification of Aguada Fénix’s vast rectangular plateau—nearly a mile long and a quarter-mile wide—which predates monumental cities such as Tikal and Teotihuacan by almost a millennium. Yet, new excavations and LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) mapping now reveal that this was only the center of an immense ritual landscape, spanning up to nine kilometers by 7.5 kilometers, making it comparable in scale to the later urban footprints of classic Maya cities.

A Monument Without Kings

Unlike the towering pyramids of later Maya kingdoms ruled by powerful monarchs, Aguada Fénix shows no signs of hierarchical governance or elite residences. Instead, evidence suggests that its construction was a collective enterprise, organized by communities rather than coercive rulers.

“There’s a long-standing assumption that large monuments required centralized power,” said Inomata. “But our data show that around 1000 B.C., people were already capable of mobilizing large-scale efforts voluntarily—motivated by shared cosmological beliefs, not by kings.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

At the heart of this finding lies a cruciform pit—a cross-shaped ritual chamber—unearthed beneath the central plaza of Aguada Fénix. Inside, archaeologists discovered a cache of artifacts that provide the earliest direct evidence of directional color symbolism in Mesoamerica. Small piles of blue, green, and yellow pigments, composed of azurite, malachite, and ochre, were meticulously arranged to correspond with the four cardinal directions, while marine shells representing red hues lay to the west and south. These offerings, dated to 900–845 BCE, reflect a cosmological worldview linking color, direction, water, and life cycles.

“This is the first time we’ve found actual pigments placed in this way,” Inomata said. “They symbolize the Mesoamerican concept of the universe’s ordered space—an idea that persisted through Maya and Aztec civilizations for more than two thousand years.”

Engineering the Sacred Landscape

LiDAR imaging and extensive fieldwork revealed that Aguada Fénix’s builders reshaped their environment on an extraordinary scale. They constructed canals up to 35 meters wide and 5 meters deep, raised causeways, and even a dam at nearby Laguna Naranjito. These features extended the cosmogram’s axes across the landscape, marking the site’s alignment with celestial events—particularly the rising sun on February 24 and October 17, which divide the 260-day Mesoamerican ritual calendar in half.

Although these hydraulic works appear unfinished, their symbolic importance outweighs their practical use. “The canals weren’t designed for irrigation or transportation,” Inomata noted. “They were likely ritual pathways or representations of cosmic water flows—a physical manifestation of their universe.”

Excavations of the dam revealed compacted layers of black clay and stone dating between 930 and 820 BCE, contemporary with the site’s main construction phase. Estimates suggest the project required over 10 million person-days of labor—a staggering feat for a society lacking both metal tools and centralized political authority.

Ritual Objects of a Shared Vision

Artifacts recovered from the site’s caches include jade ornaments carved into shapes of crocodiles, birds, and a woman giving birth—motifs symbolizing fertility, water, and transformation. Their naturalistic imagery contrasts sharply with the authoritarian iconography of later Olmec or Maya rulers.

“These objects reflect a worldview grounded in nature and community rather than divine kingship,” said co-author Xanti Ceballos, a University of Arizona doctoral researcher. “It’s remarkable that such an egalitarian society could conceive and execute a project rivaling the largest later cities in scale.”

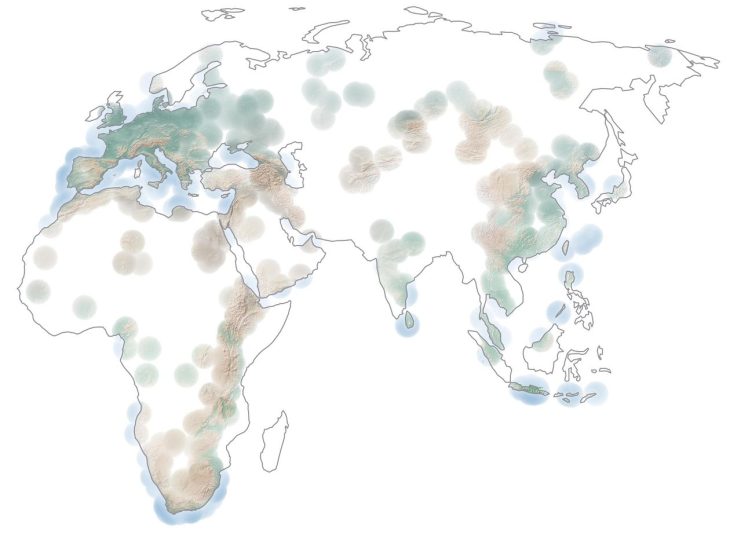

The jade and pigment materials likely came from distant sources, indicating extensive trade networks already active by the early Middle Preclassic period. Some pigments, such as azurite and malachite, would have been imported from the Mexican highlands—hundreds of miles away.

A Big Bang of Civilization

The findings at Aguada Fénix challenge traditional narratives that depict early Mesoamerican civilization as a gradual process of increasing complexity. Instead, they suggest asudden “big bang” of social and architectural innovation around 1000 BCE, when communities across the region collectively began building monumental centers.

“This discovery rewrites the early chapters of Maya civilization,” Inomata explained. “It shows that the roots of their cosmic order, calendar systems, and social organization appeared almost simultaneously with the first large-scale architecture.”

By 700 BCE, Aguada Fénix was abandoned—its canals incomplete and its ritual plazas partially buried. Yet the site’s design and symbolism deeply influenced later Maya and Mesoamerican urban planning. The cross-shaped cosmogram, the alignment to solar cycles, and the use of directional colors became enduring templates for sacred geography across the region.

Implications for Today

Beyond its archaeological importance, the discovery offers a striking reflection on human cooperation. “People often believe that great projects require powerful leaders,” Inomata said. “But Aguada Fénix shows that shared vision and collaboration can achieve monumental things without hierarchy or inequality.”

As scholars continue to analyze data from Aguada Fénix and its 478 smaller surrounding sites, the implications grow clearer: long before kings and empires, early Mesoamerican societies built not just monuments, but maps of the cosmos—in earth, pigment, and collective spirit.

Inomata, T., Triadan, D., Vázquez López, V. A., et al. “Landscape-wide cosmogram built by the early community of Aguada Fénix in southeastern Mesoamerica.” Science Advances 11, eaea2037 (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aea2037

University of Arizona Press Office; Science Advances

Cover Image Credit: Archaeologists Takeshi Inomata and Melina Garcia excavate ceremonial artifacts with pigments linked to the four cardinal directions. University of Arizona – Atasta Flores