A vanished community that once thrived on a windswept hilltop near Perth, Scotland, has resurfaced after lying buried for over two thousand years. Archaeologists from GUARD Archaeology Ltd have unveiled remarkable evidence of an Iron Age settlement at Broxy Kennels, revealing how ancient Scots lived, built, and mysteriously disappeared long before the Roman legions reached their northern frontier.

A Lost Fort Rediscovered Beneath the Cross Tay Link Road

The discovery came during large-scale excavations in 2022, part of the £118 million Cross Tay Link Road project, which includes a new bridge spanning the River Tay and six kilometres of new roadway built by BAM Nuttall Ltd. The work, commissioned by Perth and Kinross Council, unexpectedly led archaeologists to one of the most intriguing prehistoric sites in central Scotland.

“Many drivers may have no idea that as they travel this new road, they’re crossing the site of a prehistoric fort,” said Jillian Ferguson, Roads Infrastructure Manager at Perth and Kinross Council. “This project has given us an invaluable opportunity to understand how people near Perth lived over two millennia ago.”

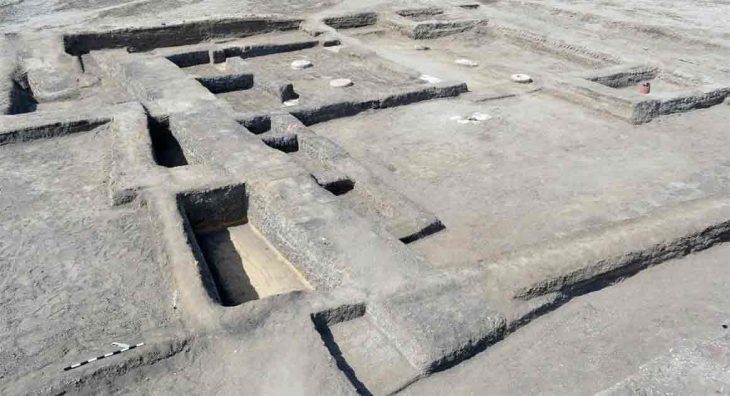

What the GUARD team found beneath the soil was a ghost settlement — its walls erased by centuries of ploughing but its story still written in the earth.

From Hidden Hillfort to Iron Age Community

The Broxy Kennels hillfort was first spotted in the 1960s through aerial photographs taken along the then-new A9 route. At ground level, there was no trace of it. Only through modern excavation could GUARD Project Officer Kenny Green and his team uncover what life looked like on this prominent bend of the River Tay between 550 and 100 BC.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“It was during the Iron Age that people chose to settle here permanently,” said Green. “They dug two massive ditches and raised earthen ramparts from the soil they excavated — an extraordinary engineering feat for its time.”

Radiocarbon dating places the earliest construction between 550 and 400 BC, with evidence of roundhouses, charred wattle panels, and daub fragments hinting at the architecture of early Scottish domestic life. While the term “hillfort” suggests a fortress, archaeologists emphasize that these were more fortified communities — visible symbols of settlement and identity rather than purely defensive structures.

Metallurgy and the Mystery of the Souterrain

Among the most fascinating discoveries were traces of Iron Age metalworking — pieces of bog ore, slag, and a vitrified tuyère (part of a bellows system for smelting). These finds confirm that Broxy Kennels was not only a place of residence but also a small-scale industrial hub where iron was smelted and shaped for tools or weapons.

Around 400 BC, the settlement underwent significant changes. One ditch was partially filled in, and a souterrain — a semi-subterranean stone chamber — was constructed. Measuring 9 metres long, 4 metres wide, and over a metre deep, it was built using rounded boulders likely gathered from the River Tay.

Roughly 200 souterrains are known across Scotland, but their purpose remains one of archaeology’s enduring mysteries. At Broxy Kennels, samples taken from the floor revealed cereal grains and chemical residues, but too little to confirm storage use. Some researchers speculate that souterrains could have served as ritual spaces, cool storage areas, or refuge chambers, though no single theory fits all examples.

A Community’s Rise and Fall

By around 300 BC, the ditches and souterrain were filled with silt and debris from collapsing ramparts, yet the settlement continued to be occupied. Radiocarbon analysis from later pits and postholes shows habitation lasting into the first century AD, ending shortly before the Roman army advanced into Perthshire.

Why the Broxy Kennels community was abandoned remains unclear. Shifting social structures, resource depletion, or external pressures — possibly the Romans — may have driven people to leave. Over the next two millennia, the once-bustling hilltop was quietly reclaimed by agriculture until nothing remained above ground.

“Centuries of ploughing eroded the hill, leaving only the deepest traces of postholes,” explained Green. “But what we’ve recovered offers an unprecedented window into Iron Age life in this region.”

Community Engagement and Legacy

The excavation wasn’t just about unearthing artefacts — it also brought the past to life for the public. During the dig, GUARD Archaeology hosted three school visits, two university tours, and several open days, attracting over 400 visitors and providing hands-on training for ten archaeology students from the University of the Highlands and Islands.

The research findings have now been published as “ARO63: Broxy Kennels Fort, Souterrain and Surrounding Landscape, Perth”, authored by Kenneth Green, John-James Atkinson, Christina Mollie Dogherty, Charlotte Hunter, Maureen Kilpatrick, and Alun Woodward. The full report is freely available through Archaeology Reports Online, ensuring that the stories of these early Scots will continue to inform and inspire future generations.

Shedding Light on Scotland’s Iron Age Identity

The Broxy Kennels excavation underscores the richness of Scotland’s prehistoric heritage, especially in the Iron Age, a period often overshadowed by later Roman and medieval histories. Through meticulous study of soil layers, charred remains, and stone structures, archaeologists are reconstructing how these resilient communities farmed, built, and forged their lives in harmony with the land.

Though time erased their homes, GUARD Archaeology’s work ensures the voices of Iron Age Scotland are not lost to the plough. What was once invisible beneath the rolling fields of Perthshire now emerges as a vivid testament to Scotland’s deep and complex past — a ghost settlement reborn through science, curiosity, and care.

Cover Image Credit: Aerial view of Broxy Kennels Fort under excavation. GUARD Archaeology Ltd