The Ephesus Massacre saw 80,000 or more Romans killed overnight during the Asiatic Vespers — one of the deadliest uprisings in ancient history.

In the twilight of the Roman Republic, far from the politics of the Senate and the splendor of the Forum, a storm was gathering in the east — quiet, calculating, and fierce. It would culminate in one of the bloodiest and most chilling massacres in antiquity: the Asiatic Vespers, orchestrated by Mithridates VI of Pontus, and executed in cities like Ephesus, where the sea meets the stone.

The year was 88 BCE. Mithridates VI of Pontus — king, rebel, and scholar of poisons — had had enough of Roman arrogance. Rome had stretched its fingers too far, digging into the soil of Asia Minor, sowing resentment in cities they called allies but treated like subjects.

The Road to Blood: Rome’s Expansion and the Rise of Mithridates

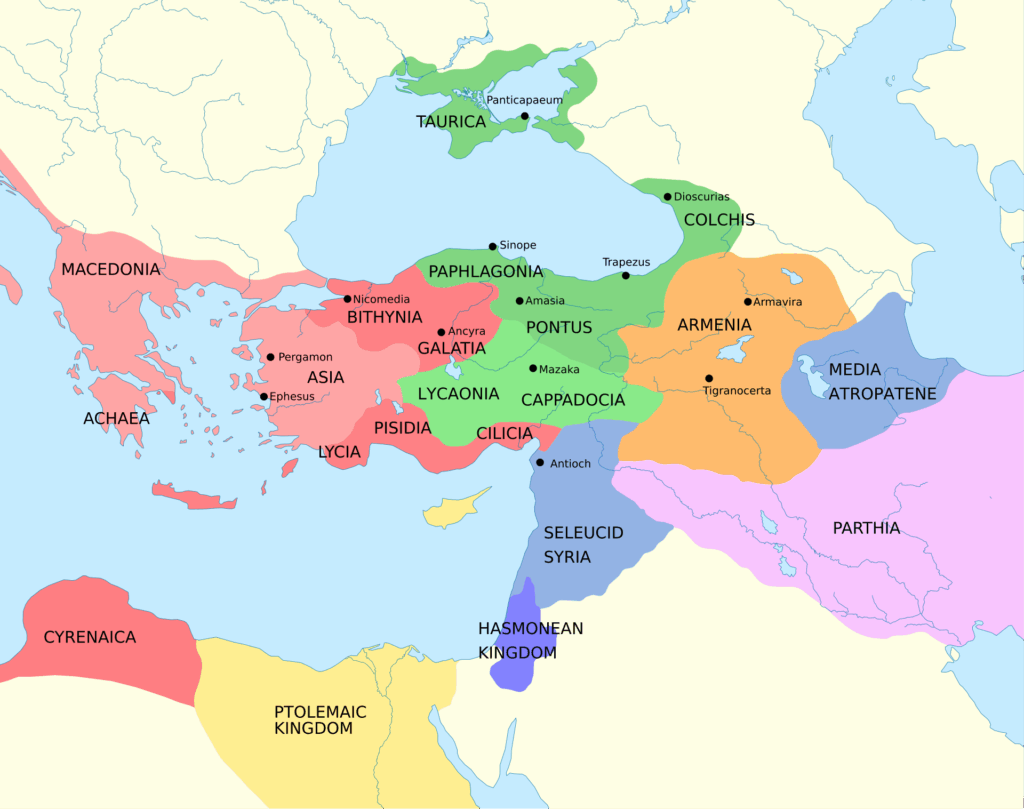

By the late 2nd century BCE, Rome’s expansion into Asia Minor had transformed local kingdoms into uneasy “allies.” Under the guise of diplomacy and protection, the Roman Republic imposed harsh taxation, corrupt governance, and economic exploitation upon cities like Ephesus, Pergamon, and Smyrna.

In this growing climate of resentment, Mithridates VI Eupator, the ambitious king of Pontus, emerged not merely as a rebel, but as a liberator in the eyes of many Anatolian Greeks. Educated, multilingual, and deeply hostile to Roman interference, Mithridates had long prepared to challenge the Republic’s dominance in the East.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Rome’s careless diplomacy only fueled his fire. When Roman governors such as Lucius Cornelius Sulla and Manius Aquillius used extortion and military threats to subdue local rulers, Mithridates began quietly forming alliances and building support among oppressed cities.

The Asiatic Vespers: Blood in the Aegean

In 88 BCE, Mithridates launched his first major offensive in what would become the First Mithridatic War. But he knew that military conquest alone would not suffice. He needed to sever Roman influence at its root — the people.

Thus came the Asiatic Vespers: a coordinated, empire-wide massacre of Roman and Italian citizens living across Asia Minor. Carried out over a single night, the violence claimed the lives of an estimated 80,000 to 150,000 Romans, with some sources suggesting even more. In Ephesus, the massacre was especially symbolic. Locals who had once feared Roman power now turned on their guests, neighbors, and even friends. Temples — once seen as sacred havens — became traps. Roman refugees who clung to altars for protection were dragged out and slain.

The name “Asiatic Vespers” draws a parallel to the Sicilian Vespers of 1282, invoking the image of a sudden, coordinated uprising — a vesper bell that rang out not salvation, but slaughter.

Why It Happened: Vengeance or Liberation?

Historians debate Mithridates’ true motives. Was this massacre a cold-blooded power move or a desperate act of anti-imperial liberation?

Political Motivation: By eliminating Roman citizens, Mithridates aimed to cripple Roman authority and discourage further colonization.

Strategic Advantage: The massacre severed Roman logistical and diplomatic lines in Asia Minor, giving Mithridates time to consolidate control.

Propaganda Tool: Framed as a “cleansing” of Roman corruption, the act rallied local populations to Mithridates’ side — at least initially.

Yet, the brutality also shocked the Roman world. It would trigger a full-scale retaliation, as Sulla was dispatched with legions to reclaim the East, leading to years of warfare and destruction.

Legacy of the Massacre at Ephesus

Though Mithridates ultimately lost the Mithridatic Wars, his defiance lingered in Roman memory for generations. The massacre in Ephesus and beyond was remembered not merely as a tragedy, but as a symbol of what happens when imperial arrogance meets resistance born from despair.

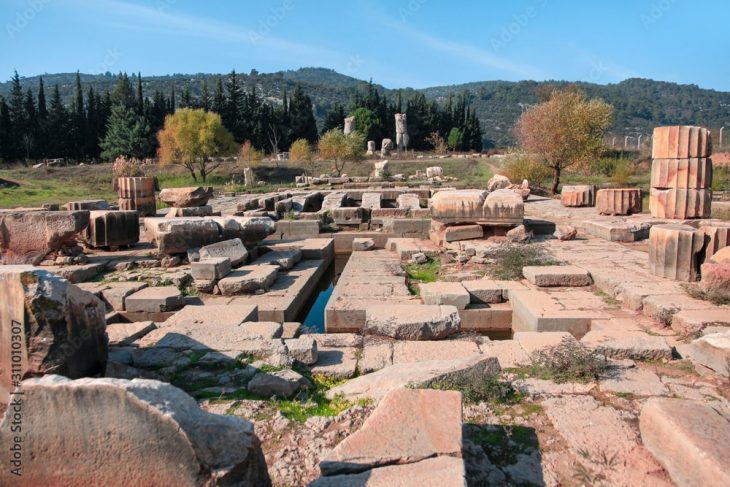

Modern archaeology in Ephesus continues to reveal layers of this complex history — from Roman villas to Pontic inscriptions, from bloodied temples to silent streets.

The Asiatic Vespers was not just an act of rebellion. It was a haunting chorus — a reminder that even empires can be caught off guard when they forget to listen to the lands they claim to rule.

Sources:

“Mithridates VI Eupator: Rome’s Deadliest Enemy” by Adrienne Mayor

The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume IX: The Last Age of the Roman Republic

Plutarch’s “Life of Lucullus” and Appian’s “Mithridatic Wars”

Note: The image titled “The Destruction of the Temple at Jerusalem” by Nicolas Poussin is included for illustrative purposes only and does not depict events related to the Ephesus Massacre or Mithridates VI.