The internet continues to buzz with the captivating notion of an immense, prehistoric tunnel network stretching from the Scottish Highlands, across the European continent, and reaching as far as Türkiye. This intriguing narrative, frequently shared on social media platforms like Instagram and Facebook, conjures images of a vast, hidden ancient world beneath our feet. However, a closer examination of archaeological findings and scientific analysis reveals a more nuanced and ultimately less fantastical reality behind these persistent claims.

The roots of this enduring story can be traced back to a misinterpretation of information surrounding “Erdstall” (German for “earth place”), mysterious underground passages discovered across Europe. A significant point of origin appears to be a 2011 article published in the respected German news magazine Der Spiegel. This article detailed these enigmatic structures, sparking public interest but inadvertently laying the groundwork for the exaggerated claims that would later proliferate online. The very act of documenting these unusual tunnels seems to have fueled subsequent imaginative leaps.

Furthermore, the narrative gained considerable traction through references to the work of German prehistorian Heinrich Kusch, who, along with his wife Ingrid, authored a book in 2009 about Erdstall tunnels. In his publication, Kusch proposed a timeline suggesting these tunnels were constructed approximately 5,000 years ago. This dating, while intriguing, stands in contrast to the findings of subsequent scientific investigations that place the origins of Erdstall tunnels much later in history.

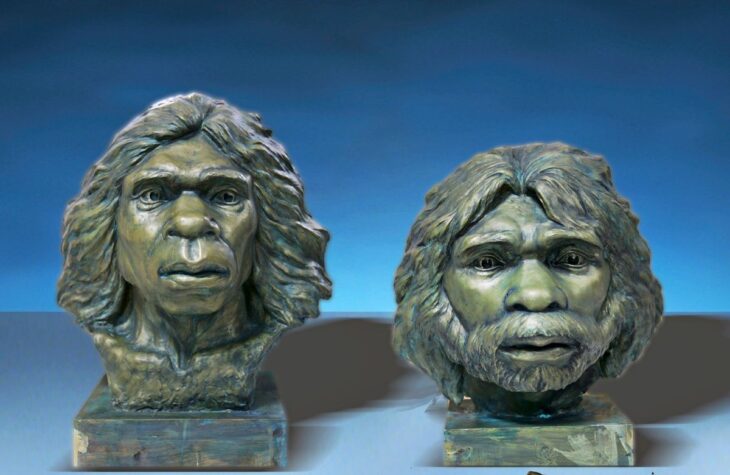

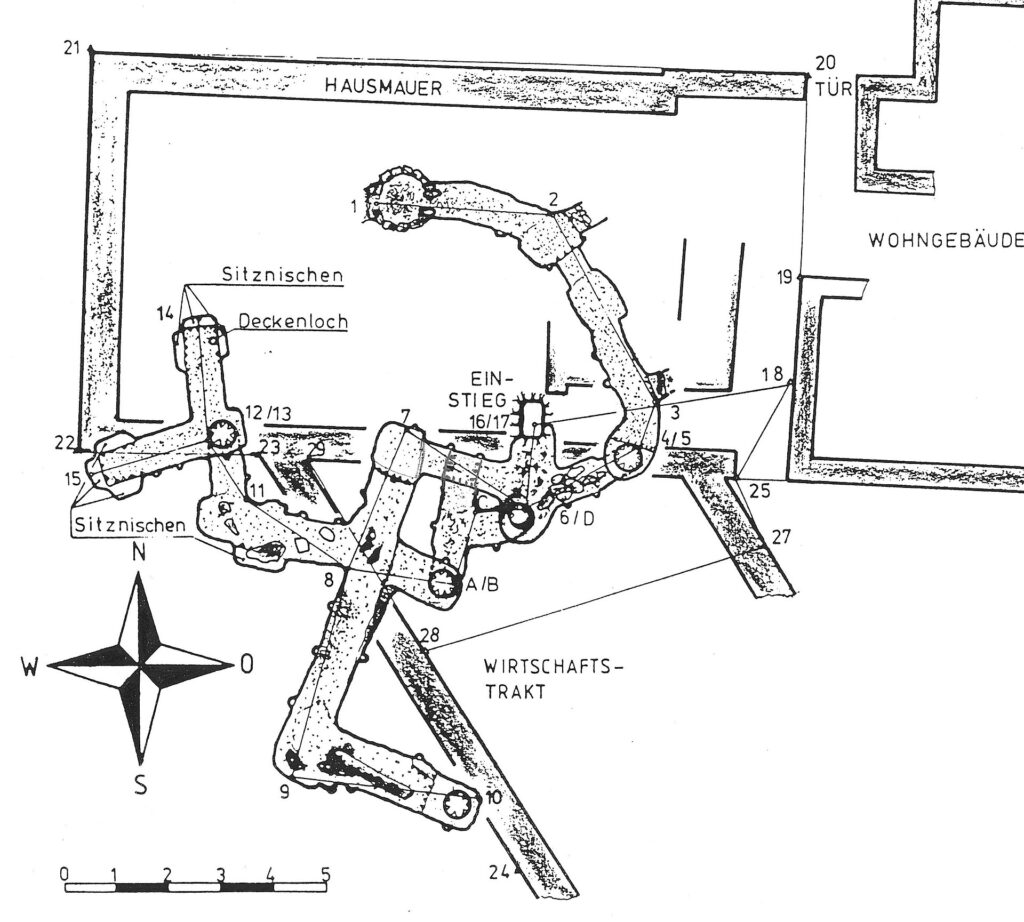

Archaeological investigations describe these Erdstall structures as typically narrow, low-ceilinged tunnels, often branching into small, confined chambers. Their diminutive size, frequently requiring individuals to crouch or crawl, has fueled numerous theories regarding their original purpose.

Erdstall structures are primarily concentrated in regions such as Germany, Austria, France, Ireland, and Scotland. This geographical distribution pattern strongly suggests localized and independent constructions rather than a single, transcontinental system. While the precise construction techniques and tools remain subjects of ongoing research, the effort required to excavate these structures with the technology of the time would have been substantial.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

While initial speculations often placed the origins of Erdstall tunnels in the distant past, even suggesting links to the Stone Age, modern dating techniques have largely refuted these early assumptions. Radiocarbon analyses consistently date the majority of known Erdstall structures to the High Middle Ages, specifically between the 10th and 13th centuries AD. For instance, charcoal fragments unearthed from Erdstall tunnels in Höcherlmühle have been dated to between 950 and 1050 AD. These findings firmly establish the construction of these tunnels centuries after the Stone Age and significantly later than the timeline proposed by Kusch.

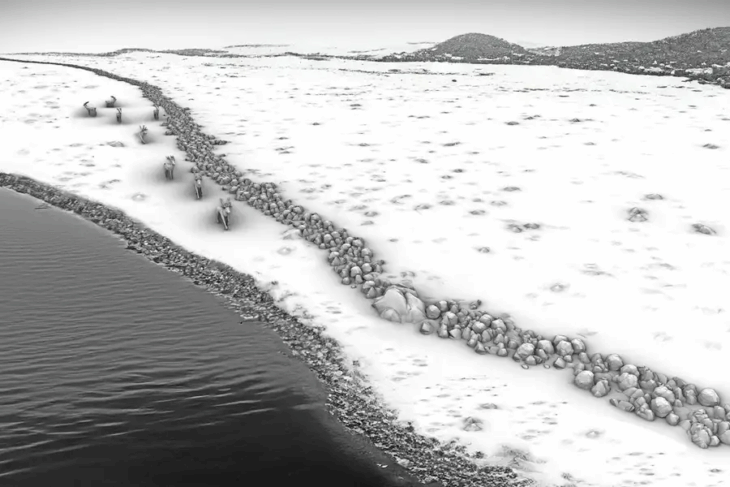

The Transcontinental Link: A Geographically and Logistically Implausible Scenario

The assertion of a continuous underground passage spanning from Scotland to Türkiye presents significant geographical and logistical hurdles. The sheer distance involved, coupled with the formidable natural barriers such as the North Sea and the English Channel, renders the construction of such a network with the technology of the purported era virtually impossible. The archaeological record lacks any evidence of such a monumental and coordinated engineering undertaking.

Instead, these tunnels are a collection of unconnected passageways primarily found in regions of Germany, Austria, France, Ireland, and Scotland.

Intriguingly, the distribution of Erdstall tunnels shows some parallels with the routes of Irish-Scottish traveling monks who journeyed across the continent as missionaries starting in the 6th century. However, this connection doesn’t support the idea of a continuous, ancient tunnel network stretching thousands of kilometers.

Cappadocia’s Subterranean Cities: A Distinct Archaeological Phenomenon

While the Erdstall tunnels remain shrouded in mystery regarding their original purpose—ranging from shelters to spiritual spaces—there is no evidence to support the notion of a vast, ancient network stretching across Europe. In contrast, Türkiye’s Cappadocia region has revealed sophisticated underground cities like Derinkuyu, which served as refuge during times of danger, showcasing a different context of underground construction.

The articles correctly highlight the existence of remarkable underground cities in Türkiye’s Cappadocia region, with Derinkuyu being a prime example. These extensive complexes, featuring intricate living spaces, ventilation shafts, and defense mechanisms, showcase advanced ancient engineering. However, these subterranean urban centers are distinct from the European Erdstall tunnels in terms of their scale, purpose (primarily shelter and habitation), and architectural sophistication. They represent a separate cultural and engineering achievement and do not lend credence to the idea of a continuous link with the Erdstall systems of Western Europe.

Unraveling the Purpose: Scientific Inquiry into Erdstall Functionality

The precise function of Erdstall structures remains a subject of scholarly debate. Various theories have been proposed, including their use as defensive refuges, storage facilities, sites for religious or spiritual practices, or even for more mundane purposes such as animal shelters.. The frequent absence of artifacts or remains within these tunnels complicates the determination of their original intent. Some researchers suggest that the seemingly “cleaned-out” nature of many Erdstall structures hints at specific, perhaps ritualistic, uses.

In conclusion, while the enduring mystery of Europe’s Erdstall tunnels continues to fascinate, the claim of an ancient, uninterrupted underground network stretching from Scotland to Türkiye lacks credible scientific and archaeological support. The Erdstall structures represent localized phenomena dating to the Middle Ages, and the notion of a transcontinental link is geographically and logistically improbable. The impressive underground cities of Cappadocia, while equally captivating, belong to a different historical and cultural context. The persistence of such intriguing myths underscores the importance of critical thinking and the reliance on evidence-based analysis when evaluating extraordinary claims. Investigating these topics through scientific literature and archaeological findings allows for a more accurate understanding of our past and the fascinating, yet often less sensational, realities it holds.

Cover Image Credit: Entry to the Ratgöbluckn erdstall at Perg, Austria. Wikipedia