A recent study sheds light on the often-overlooked contributions of women in the production of handwritten manuscripts during the Middle Ages. While the image of a monk diligently copying texts is a common representation of this era, the role of female scribes has remained largely unquantified until now. The research estimates that over 10 million manuscripts were produced in the Latin West between 400 and 1500 CE, with approximately 750,000 still in existence. However, the specific contributions of women to this body of work had not been previously assessed.

A recent study published in Humanities and Social Sciences Communications uncovers a significant truth: women played a crucial role in manuscript production. Researchers from the University of Bergen in Norway have found that at least 1.1% of medieval manuscripts were transcribed by female scribes, suggesting that the number could exceed 110,000 manuscripts.

Led by scholar Åslaug Ommundsen, this research represents the first comprehensive quantitative analysis of the contributions of female scribes. In an interview with Hyperallergic, Ommundsen stated, “Our study provides statistical support for the often-overlooked contributions of female scribes throughout history.” While individual instances of women participating in manuscript copying, particularly within monastic scriptoria, have been documented in previous studies, a large-scale numerical assessment had been notably absent until now.

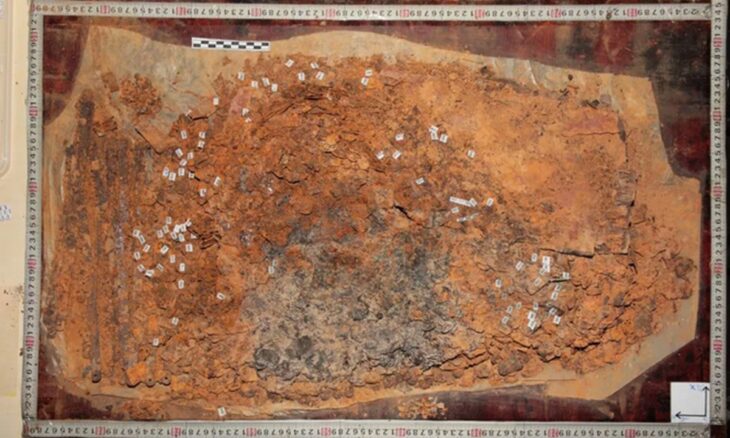

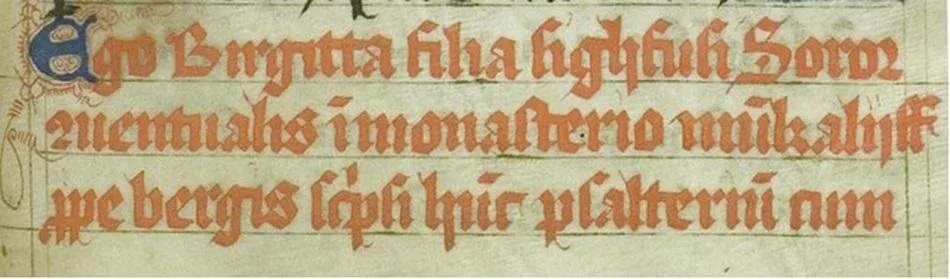

The study, which presents the first bibliometric analysis of female scribes, focuses on colophons—brief statements found at the end of manuscripts that often include the names of the scribes, the individuals who commissioned the work, and other relevant details. Utilizing the Benedictine colophon catalogue, which contains 23,774 entries, the researchers identified that only 1.1% of these manuscripts (dating from around 800 to 1626 CE) were definitively copied by female scribes. This figure, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.9% to 1.2%, is considered a conservative estimate, suggesting that at least 110,000 manuscripts may have been produced by women, with around 8,000 still extant.

The findings indicate a consistent, albeit small, contribution from female scribes throughout the Middle Ages. While the number of verifiable female scribes is limited, the study implies that there are likely many more women and book-producing communities yet to be identified.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The research builds on previous studies of monastic scriptoria for women, highlighting the contributions of various female religious institutions and the participation of women in manuscript production across different regions and time periods. Despite the emerging field of quantitative codicology, no prior attempts had been made to quantify the contributions of female scribes.

The methodology involved a thorough examination of the Benedictine colophon catalogue, where the authors identified female scribes based on specific linguistic markers in the colophons. The study acknowledges the limitations of the catalogue, including potential inaccuracies in dating and the exclusion of domestic literacy, which may have further obscured women’s contributions.

The results reveal that of the 23,774 colophons analyzed, 254 were attributed to female scribes, with 204 of these being named. The study also notes that the percentage of female scribes remains statistically consistent across both named and anonymous colophons, despite a higher number of unidentified entries in the anonymous group.

The researchers caution that the 1.1% figure is likely a lower bound, as various factors may have influenced the visibility of female scribes in historical records. For instance, women may have concealed their gender in colophons or been less likely to write them altogether. Additionally, the survival rates of manuscripts may have varied by gender and geography, potentially skewing the data.

The study concludes that while the contribution of female scribes was limited in percentage terms, it was significant enough to warrant further investigation into the roles of women in manuscript production. The findings suggest that the increased market for vernacular manuscripts around 1400 may have led to a rise in female participation, although the overall contribution of women remained modest compared to their male counterparts.

This groundbreaking research not only highlights the importance of female scribes in the Middle Ages but also calls for a reevaluation of historical narratives that have traditionally marginalized women’s contributions to literature and scholarship.

Ommundsen, Å., Conti, A.K., Haaland, Ø.A. et al. (2025). How many medieval and early modern manuscripts were copied by female scribes? A bibliometric analysis based on colophons. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 346. doi:10.1057/s41599-025-04666-6

Cover Image Credit: Illustration in a 12th-century homiliary, showing a self-portrait of the female scribe and illuminator Guda. The text band in the letter reads: “Guda peccatrix mulier scripsit et pinxit hunc librum” (Guda, a sinner wrote and painted this book). Credit: Å. Ommundsen et al., Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (2025)