On a low rise overlooking the upper reaches of the Tigris River, archaeologists are revisiting one of humanity’s most transformative chapters. At Çayönü Tepesi, a 12,000-year-old settlement in southeastern Türkiye, human bones buried for millennia are now yielding genetic clues that may redefine how the world’s earliest farming societies emerged, organized themselves, and interacted across vast regions.

Known for decades as a key site in the transition from foraging to agriculture, Çayönü is now at the center of an ambitious interdisciplinary project that combines archaeology, physical anthropology, and ancient DNA research. The goal is not only to understand how people lived here, but also who they were, where they came from, and how deeply connected they were to neighboring regions such as Mesopotamia and the Caucasus.

A Landmark Site in the Birth of Sedentary Life

Located near the modern town of Ergani, Çayönü was first identified during surface surveys in 1963 and excavated beginning in 1964 by Halet Çambel and Robert J. Braidwood. From the outset, the site stood out. Unlike temporary camps typical of mobile hunter-gatherers, Çayönü revealed long-term settlement, planned architecture, and evidence for early plant cultivation and animal management.

These discoveries placed the site among a small group of Neolithic settlements that fundamentally altered prevailing theories about where and how agriculture began. Rather than a single “origin point,” Çayönü suggested a complex mosaic of innovation, experimentation, and cultural exchange across Upper Mesopotamia and southeastern Anatolia.

After a long interruption due to security concerns in the 1990s, excavations resumed in recent years with renewed scientific scope and modern analytical tools.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Scientific Leadership and Fieldwork

The current excavation program is conducted under the scientific directorship of Assoc. Prof. Dr. Savaş Sarıaltun from Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, with anthropological and bioarchaeological studies coordinated by Prof. Dr. Ömür Dilek Erdal of Hacettepe University. The project brings together specialists from ten universities across Türkiye and operates with permission from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

Since May 2025, teams have conducted intensive excavations over an area exceeding 3,200 square meters. These efforts have exposed a remarkably continuous occupation sequence, from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic through the Pottery Neolithic and into the Early Bronze Age.

Among the most striking discoveries are grid-planned buildings dated to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B phase (approximately 9000–8500 BCE), a large communal structure believed to have hosted gatherings or collective activities, and a carefully engineered water channel from the Bronze Age. Together, these features point to a settlement that was deliberately planned and socially coordinated, rather than organically improvised.

Burials, Objects, and Social Signals

Excavations have also revealed an Early Bronze Age cemetery dated to around 2900–2750 BCE. Eight graves have been investigated so far, seven belonging to the Early Bronze Age and one to the Neolithic period. The burials contained pottery vessels, copper and bronze objects, tools, daggers, and two seals discovered in the surrounding area.

According to Sarıaltun, these seals are particularly significant. They suggest the existence of early economic networks and possibly indicate social roles or group identities within the community. Yet despite such material distinctions, the overall burial record does not point to rigid social hierarchies.

From Excavation House to Laboratory

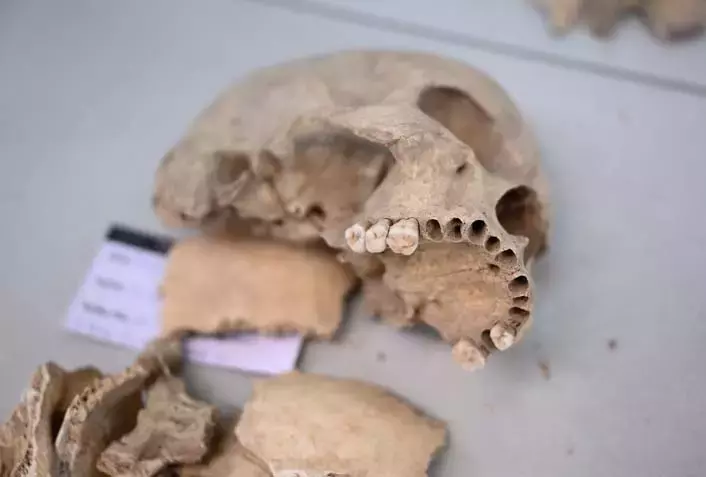

All skeletal remains are first documented at the Çayönü excavation house, then transferred—following official permits—to Hacettepe University’s anthropology laboratories. There, Prof. Erdal and her team carry out detailed cleaning, restoration, and analysis according to international standards.

To date, approximately 255 individuals have been studied, making Çayönü one of the most comprehensively analyzed Neolithic populations in the region. The results depict a highly heterogeneous community, both biologically and culturally.

Skeletal markers reveal a physically demanding way of life. Even children show evidence of early participation in agricultural work and daily labor. Differences between individuals buried in larger and smaller houses do not translate into clear biological signs of inequality. People across the settlement appear to have shared similar workloads and burial customs.

Gender-based divisions of labor are visible but balanced. Men display markers associated with herding and outdoor activity, while women show patterns linked to repetitive indoor production. Both roles were essential to the community’s survival.

DNA and Long-Distance Connections

The most transformative aspect of the project lies in its genetic research. By analyzing ancient DNA, researchers are reconstructing kinship patterns, mobility, and population dynamics over thousands of years.

Preliminary findings indicate that Çayönü was far from isolated. Genetic signatures point to sustained connections with Mesopotamia and the Caucasus, showing that individuals from outside regions settled at the site and became integrated into the community.

“These connections are not theoretical,” Erdal notes. “We can observe them directly in the genome. People moved, mixed, and formed new social bonds here.”

The DNA research is ongoing and expected to continue for several years, with comprehensive results planned for public release between 2026 and 2027.

Rethinking Early Societies

Together, the archaeological and genetic evidence from Çayönü challenges simplified narratives of early civilization. Rather than a straightforward march toward hierarchy and inequality, the site reveals a community that was organized, cooperative, and deeply interconnected with its wider world.

In tracing the genetic footprints of some of the first farmers, Çayönü is helping scientists answer a question that still resonates today: how did humans learn to live together in permanent communities—and what did they gain, and lose, in the process?

Cover Image Credit: AA