Ancient Mayan masons had their own secrets for making lime plasters, mortars, and plasters, which they used to build their magnificent structures, many of which still stand today.

A team of mineralogists and geologists at the University of Granada has discovered the secret ingredient that made Mayan plaster so durable.

The team has analyzed samples of Maya plasters from Honduras and confirmed that the Maya added plant extracts to improve the plasters’ performance, according to a new paper published in the journal Science Advances.

The team collaborated with local Maya-descended masons in Copán, Honduras, which was a major Maya center prior to Spanish colonization of Central America, to learn how the plaster was made. The approach involves adding the sap from the bark of local tree species, Chukum and Jiote when the lime – the umbrella term for calcium oxides rather than the delicious fruit – is mixed with water, a process called slaking.

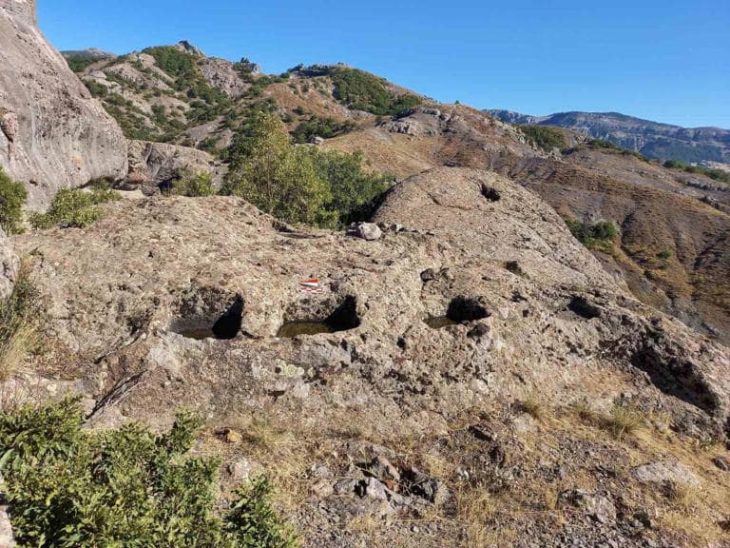

![Maya plasters from Copan archaeological site (Honduras). (A) General view of Structure 10L-16 (Late Classic building dedicated in 776 CE) (22). Within this structure is located substructure “Rosalila” (540 to 655 CE), the best example of a complete Classic temple in the Maya area, whose surface is decorated with pinkish lime plaster and stucco masks (B). Samples MCopan-10 and MCopan-11 were collected from the latter location, shown (marked with a red star) in the site map (C). Samples MCopan-1 (D) and MCopan-2 (E) corresponding to coarse lime plasters from the interior wall of the central room of Structure 12, ca. 700 CE [blue star in (C)]. Samples MCopan-3 (F) and MCopan-4 (G) corresponding to a fine two-layer plaster (“stucco”) floor from the mid-Classic (500 to 700 CE) collected in tunnel 74 at Structure 10L-16. (C) adapted from (22) with permission from Springer Nature. Photo: Science Advances (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adf6138](https://arkeonews.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Maya-plasters-min-scaled-e1682020701667-1024x840.jpeg)

A comparison of plaster and stucco from 540 to 850 CE and those created by the team today reveals a striking resemblance. Maya masons most likely used sap-infused plaster because of its increased durability, plasticity, and water resistance.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Since ancient times, and in some cases even earlier, plaster, cement, and concrete have been used. These now-ubiquitous building materials have been used and improved by numerous civilizations, but not always the exact recipes used by our forebears are passed on intact, as in this instance. Archaeologists occasionally have to put in a lot of effort to understand how these materials were made.

“Our study helps to explain the improvement in the performance of lime mortars and plasters with natural organic additives developed not only by ancient Maya masons but also by other ancient civilizations (e.g., ancient Chinese sticky rice lime mortars),” the authors wrote in the paper.

The study is published in Science Advances.