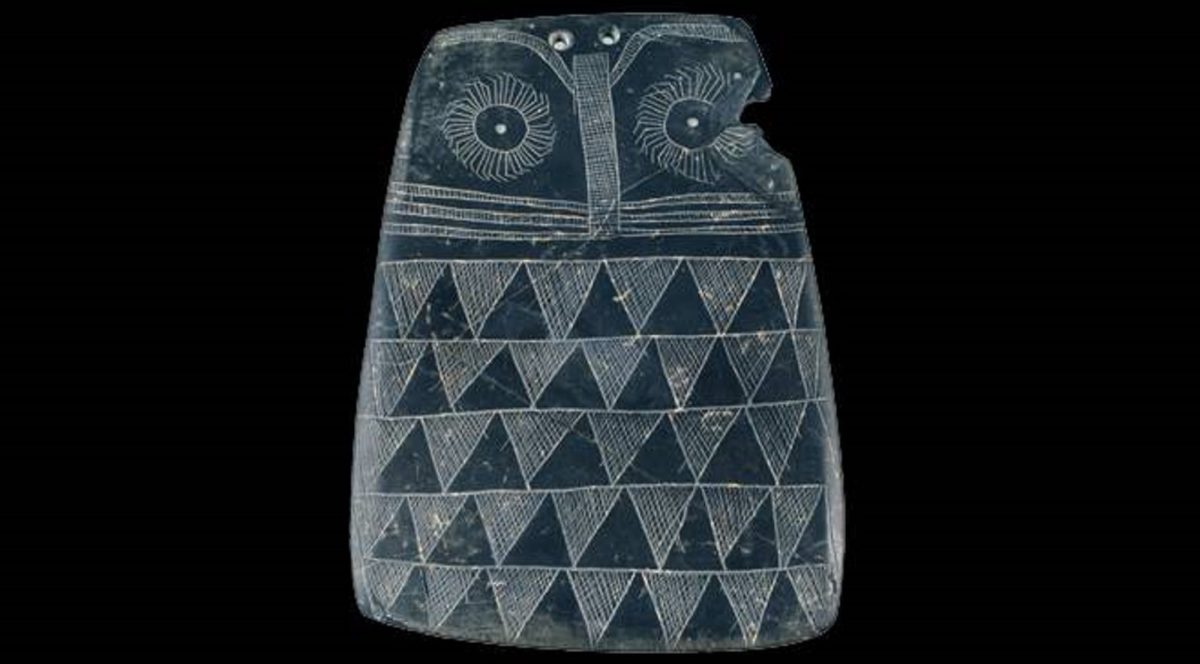

A New Study of 5000-year-old copper age ancient owl-shaped slate engraved plaques suggests that they may have been ancient toys made by children.

Archaeologists have discovered countless tiny owl-shaped plaques hidden in tombs, pits, and crevices all over the Iberian Peninsula since the late 19th century. However, no one has been able to completely agree on what these tiny slate treasures may have once stood for many years.

Some claim they were religious artifacts, possibly serving a symbolic function for their creators. Others suspected they were goddess idols prayed to in times of distress. Others have argued that the owl replicas were made in honor of the dead rather than as mystical objects.

Now, Juan José Negro and colleagues re-examined these interpretations and suggest instead that these owl plaques may have been crafted by young people based on regional owl species, and may have been used as dolls, toys, or amulets.

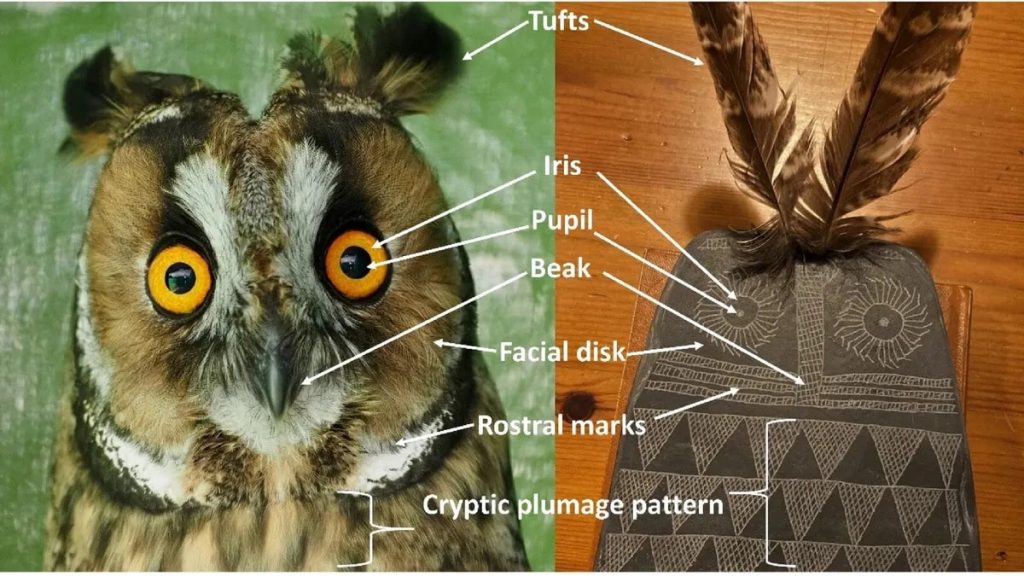

On a scale of one to six, the authors graded 100 plaques according to how many of six owl characteristics they exhibited, including two eyes, feathery tufts, patterned feathers, a flat facial disk, a beak, and wings. The authors found many similarities between 100 contemporary owl drawings made by kids between the ages of four and thirteen and these plaques. Owl drawings more closely resembled owls as children aged and became more skillful.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“Owl engravings could have been executed by youngsters, as they resemble owls painted today by elementary school students,” the study authors write. “This also suggests that schematic drawings are universal and timeless.”

Many of the plaques have two holes at the top, which the team believes makes threading string through them to hang them as ritual objects impractical. Instead, Juan José Negro speculates that the holes were used to insert feathers, representing the feathered tufts, similar to ears, that some owl species in the area have on their heads, such as the long-eared owl or Asio otus.

“If stone toys were made at the end of the stone age, metal tools in subsequent periods surely made easier the carving of wood figurines, which would hardly leave any traces in the archaeological records,” the authors write.

“Similarly, skin or textile pieces would disintegrate quite rapidly. Therefore, owl-like objects made in stone provide perhaps one of the few glimpses to childhood behavior in the archaeological record of ancient European societies.”

The researchers speculate that children may have used their owl toys as pieces of a larger game similar to Monopoly’s shoe, car, and thimble, except that each child may have had a special plaque.

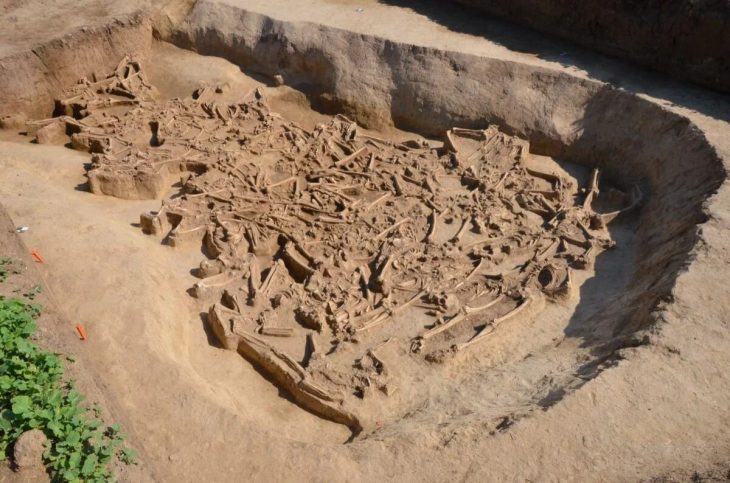

That uniqueness might explain why some of the models were found in tombs. Children who passed away may have been interred with their small, inanimate companion, or at the very least, adults may have considered the figurines significant enough to be used in funeral rites for sentimental reasons.

That would explain why something made of slate – a plentiful material at the time – would be used for funeral practices where opulent gems and gold were typically used.

Another hypothesis is that the owl relics could’ve been characterized as dolls. Some of the plaques appeared to be painted and dressed with textiles.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23530-0

Cover Photo: Valencia plate. Seville Archaeological Museum / Ministry of Culture