The double-headed eagle is one of the most enduring symbols in human history. Recognized today as an emblem of imperial power, religious authority, and cultural heritage, its origins stretch back over 4,000 years. While commonly associated with the Byzantine Empire and the Eastern Orthodox Church, the double-headed eagle’s story begins much earlier—in the royal courts of the ancient Hittites, and even before that, in Mesopotamian religious symbolism.

Hittite and Mesopotamian Origins

According to archaeological and iconographic research, including Chariton’s academic study, the double-headed eagle first appeared in Hittite art during the 2nd millennium BCE, influenced by even earlier Mesopotamian motifs. In these contexts, the double-headed bird symbolized sovereignty, protection, and divine favor.

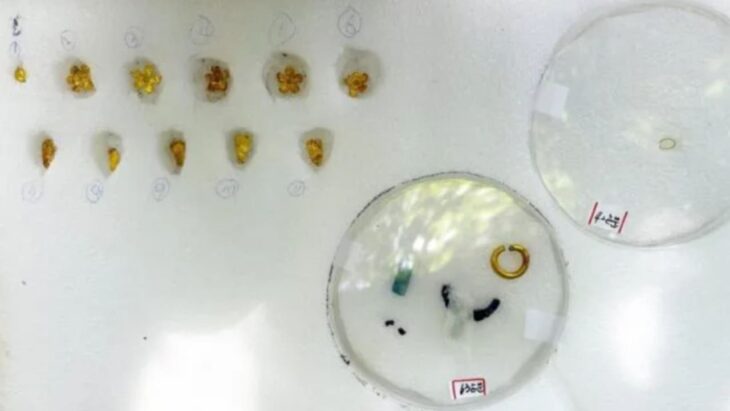

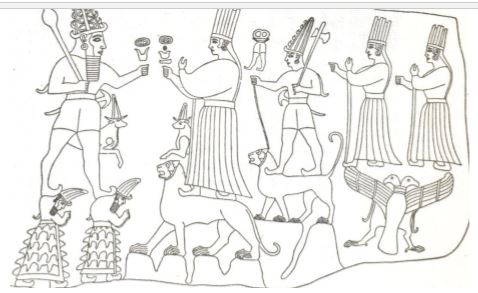

Notable examples include:

Seals and sculptures from Hattusa and Alaca Hüyük, depicting the eagle supporting royal or divine figures.

The Sphinx Gate at Alaca Hüyük, where the eagle grasps prey in its talons—an indication of power over life.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

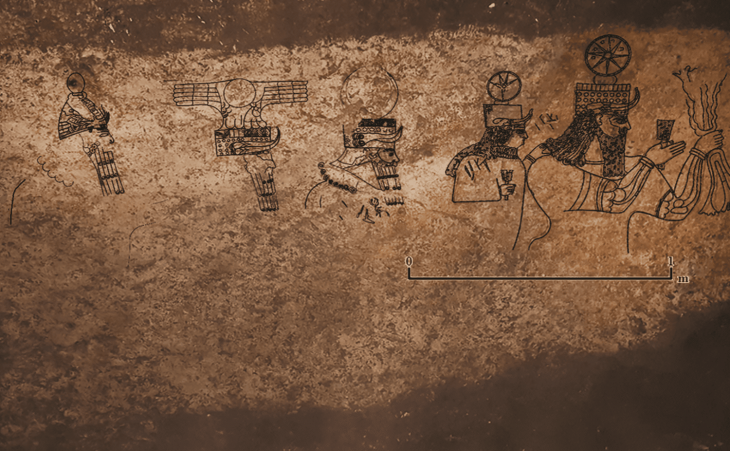

Yazılıkaya sanctuary, where the eagle supports goddesses from the Hurrian pantheon, symbolizing celestial authority.

Mesopotamian precursors, such as the lion-headed eagle Imdugud (Anzu), suggest that this motif migrated and transformed through Hittite culture, serving both religious and royal purposes.

Symbolic Meanings and Iconography

In Hittite culture, the double-headed eagle was more than decorative:

Two heads may have symbolized vigilance over dual realms—sky and earth, or war and peace.

The eagle’s association with falconry also reinforced its connection to nobility and control.

The motif often appeared alongside twisted bands and supporting human figures, hinting at cosmological or dynastic themes.

These features likely carried forward as the motif spread through Anatolia and into Eastern Europe.

Byzantine Empire and Christian Symbolism

The double-headed eagle re-emerged as a dominant symbol in the 10th century, adopted by the Byzantine Empire as a mark of imperial unity. Under Emperor Isaac I Komnenos, the eagle gained its distinctive two heads, representing dominion over both East and West.

By the 13th century:

It became the emblem of the Palaiologos dynasty, symbolizing the fusion of church and state under the doctrine of Symphonia.

The yellow-and-black eagle flag became a visual representation of Orthodox Christianity and the spiritual supremacy of the Byzantine court.

Adoption Across Cultures and Religions

As the Byzantine Empire interacted with surrounding powers, the double-headed eagle was adopted by:

Islamic rulers in Spain and the Seljuk Empire, appearing on coins and banners.

The Holy Roman Empire, where it was seen as a symbol of divine imperial rule.

Russian Tsars, especially after Ivan III married Sophia Palaiologina, claiming continuity with Byzantine authority.

Interestingly, in India, a similar symbol known as Gandaberunda emerged in Hindu mythology, linked to Vishnu’s destructive and regenerative powers. The double-headed bird appears in temple frescoes, stupas, and even Vijayanagara coins—demonstrating the motif’s cross-cultural resonance.

Symbol in the West and Modern Times

Crusaders may have first encountered the emblem via Seljuk banners during their travels, later introducing it to Western Europe. It soon became popular in:

France, among nobility with chivalric mottos.

Italy, particularly on ducal arms like that of Modena.

England, where it adorned the heraldry of knights like Robert George Gentleman.

In modern times, the symbol persists:

As the official emblem of the Greek Orthodox Church.

In national coats of arms (e.g., Albania, Serbia, Russia, Montenegro).

In sports, notably the Greek football club AEK Athens, founded by Constantinopolitan refugees.

Another prominent example of the double-headed eagle in modern state symbolism is found on the national flag of Montenegro. Adopted in 2004 and rooted in earlier heraldry of the Petrović-Njegoš dynasty, the emblem features a golden double-headed eagle, clearly influenced by the Byzantine imperial model. This symbol not only represents Montenegro’s sovereignty but also reflects its historical and religious connections to Eastern Orthodoxy and the Byzantine tradition. The eagle bears a scepter and an orb—symbols of monarchical authority—while the central shield depicts a golden lion passant, underlining both continuity and independence.

From its mysterious Mesopotamian origins and regal Hittite appearances to its imperial Christian adoption and global diffusion, the double-headed eagle remains a timeless symbol of power, duality, and legacy. Whether carved into ancient gates or emblazoned on modern flags, it continues to fascinate and inspire, bridging the past with the present.

Source: Chariton, J. D. (2011). The Mesopotamian origins of the Hittite double-headed eagle. UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research, 14, 1–13.

Alexander, R. L. (1989). A great queen on the Sphinx piers at Alaca Hüyük. Anatolian Studies, 39, 151–158. https://doi.org/10.2307/3642873

Canby, J. V. (2002). Falconry (Hawking) in Hittite lands. Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Studies, 61(3), 161–201.

Collins, B. J. (2010). Animal mastery in Hittite art and texts. In D. B. Counts & B. Arnold (Eds.), The master of animals in Old World iconography (pp. 59–74). Archaeolingua Foundation.

Porada, E. (1993). Why cylinder seals? Engraved cylindrical seal stones of the Ancient Near East, fourth to first millennium B.C. The Art Bulletin, 75(4), 563–582.

Cover Image Credit: The central scene of the shrine of Yazilikaya Chamber A, with the double-headed eagle supporting two goddesses (Akurgal 1973:Figure 151)