In Chile, an unusual cemetery has been discovered that contains the well-preserved remains of prehistoric flying reptiles that flew over the Andean country’s Atacama desert 100 million years ago.

The remains belong to pterosaurs, flying creatures that lived alongside dinosaurs and fed by filtering water through long thin teeth – similar to flamingos.

Although their fossil remains are infrequently found, pterosaurs were probably the most abundant winged, backboned animals of the dinosaurian era (230 to 65 million years ago).

The group of scientists, led by Jhonatan Alarcon, an investigator at the University of Chile, have been searching for pterosaurs for years, but this discovery surpassed their hopes.

The find was made about 40 miles from another site where other pterosaur remains had been found, supporting a theory these reptiles were once widespread in Chile.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The discovery of this rare cemetery will allow scientists to study the pterosaur’s habits, not just its anatomy.

“This has global significance because these kinds of discoveries are uncommon. We would be able to figure out how these animals formed colonies and whether or not they nurtured their young,” Jhonatan Alarcon said.

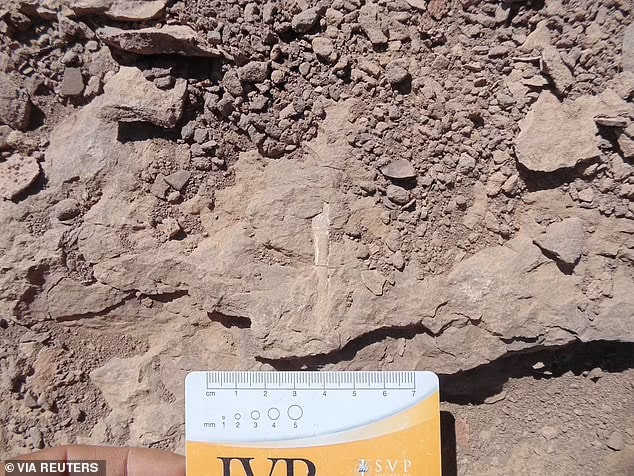

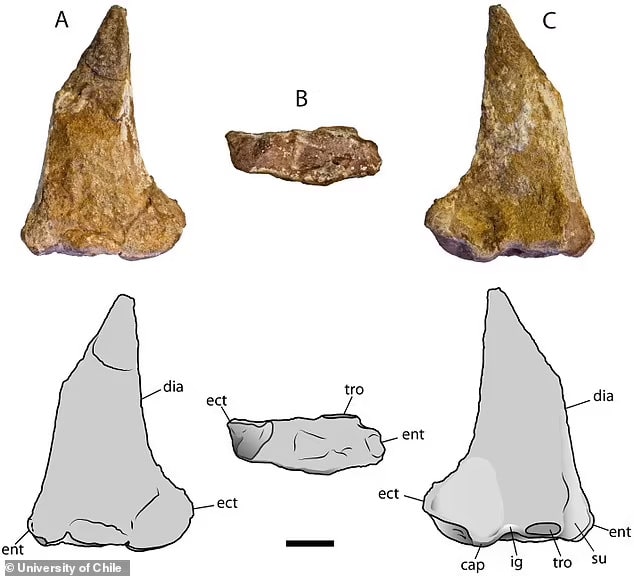

Another surprising revelation was how well-preserved the bones recovered were, providing scientists a stronger insight into how they formed.

‘Most pterosaur bones that are found are flattened, broken,’ said David Rubilar, head of paleontology at Chile’s Museum of National History. ‘Nevertheless we were able to recover preserved three-dimensional bones from this site.’

The remains were discovered in an area that would have been a tidal estuary of the Quebrada Monardes Formation in the Lower Cretaceous, 100 million years ago.

The new locality, which is named “Cerro Tormento”, is in Cerros Bravos in the northeast Atacama region, Northern Chile.

The team found four cervical vertebrae, with one belonging to a particularly small pterosaur, confirming that they belonged to multiple individuals.

What they can’t say is whether there were multiple species of pterosaur present, or if they all belong to the same species.

‘This finding is the second geographic occurrence of pterosaurs of the clade Ctenochasmatidae in the Atacama region, although it is currently uncertain if ctenochasmatids from both locations were contemporaneous,’ they wrote.

‘This suggests that the clade Ctenochasmatidae was widespread in what is now northern Chile,’ the authors added.

Ctenochasmatidae is a group of pterosaurs characterized by their distinctive teeth, which are thought to have been used for filter-feeding.

‘In addition, the presence of bones belonging to more than one individual preserved in Cerro Tormento suggest that pterosaur colonies were present at the southwestern margin of Gondwana during the Early Cretaceous.’

Gondwana was an ancient supercontinent that broke up about 180 million years ago, eventually splitting into Africa, South America, Australia and Antarctica.

It was reported that Pterosaurs have diversified into dozens of species. Some were the size of an F-16 fighter plane, while others were the size of a sparrow.

Pterosaurs were the first group of vertebrate animals to adopt an aerial lifestyle. They had no competition in the air for about 90 million years, until the evolution of birds in the Late Jurassic Period.

The findings have been published in the journal Cretaceous Research.