Archaeologists excavating the remote Bremenium Roman Fort in High Rochester, Northumberland, have uncovered two exquisite intaglios—engraved gemstones once set into signet rings—that illuminate the far-reaching cultural connections of Rome’s northernmost soldiers. These rare artifacts, found during the 2025 excavation season, have been described as “exceptional in both quality and quantity,” setting a new record for discoveries at the site.

Rediscovering a Frontier Outpost

Bremenium Fort, situated just north of Hadrian’s Wall on the line of the Roman road Dere Street, served as a key military outpost during the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD. Established to guard one of the empire’s northern gateways into Caledonia (modern-day Scotland), the fort was home to auxiliary units drawn from across the Roman world, including the Cohors I Lingonum from Gaul and later the Cohors I Vardulorum from Hispania.

Today, its grassy ramparts and stone foundations stand amid the rolling landscape of the Northumberland National Park. But beneath that surface, archaeologists are uncovering vivid traces of everyday life—and rare glimpses into the identities of the soldiers and civilians who once lived here.

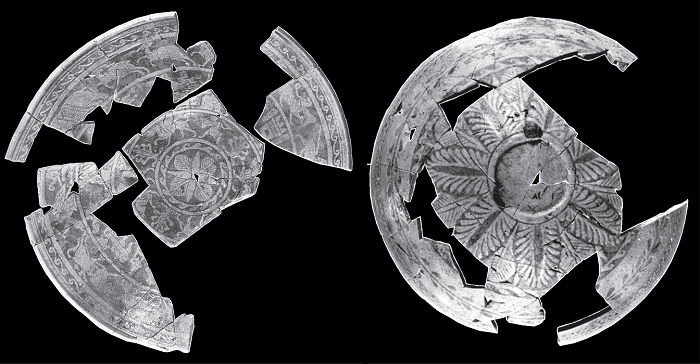

The Discovery of the Intaglios

During the fifth consecutive year of excavations in summer 2025, a team of 47 volunteers and 24 Newcastle University archaeology students unearthed two finely carved gemstones. The finds were made in close succession: the first, discovered by volunteer Barry Mead on the opening day of the dig, depicts an elaborate grape-harvesting scene featuring two cupids beside a goat-like creature. Experts believe the image to be unique in Britain and northern Europe, though stylistic parallels exist in Dalmatia (modern Croatia) and northern Italy.

The second intaglio, smaller but equally sophisticated, may also have adorned a high-status ring. Both are believed to have served as signet ring inserts, used by Roman officers or traders to stamp personal seals in wax or clay. Their intricate artistry and Mediterranean iconography suggest that their owners hailed from the southern provinces—or at least wanted to project an identity rooted in the cultured heartlands of the empire.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Archaeologist Richard Carlton, who oversaw the excavations, noted that “these gems were probably worn by men of means—officers or administrators stationed on the frontier. The craftsmanship points to Mediterranean origins, perhaps imported through long-distance trade or carried here by their owners.”

Symbols of Identity and Connection

In Roman culture, intaglios were far more than decorative jewelry. They served as personal identifiers, status symbols, and even spiritual talismans. Each carved stone bore imagery reflecting the wearer’s values, profession, or divine protector—ranging from deities and animals to mythological or agricultural scenes.

The Bremenium grape-harvest motif is especially revealing. Grapes symbolized abundance, fertility, and Bacchic celebration, connecting the harsh northern frontier with the sun-soaked vineyards of the Mediterranean. Finding such imagery in the cold hills of Northumberland speaks volumes about the resilience and cultural memory of Rome’s expatriate soldiers.

As Barry Mead put it, “the most exciting part is knowing I’m the first person to see this in 1,800 years.” His discovery offers a tangible link to the lives of individuals who served thousands of miles from home, yet carried with them symbols of comfort, faith, and heritage.

A Record Year for Discoveries

The 2025 Bremenium excavation yielded not only the two intaglios but also a wealth of Roman pottery, military equipment, brooches, amphora fragments, and a bronze oil lamp. Bob Jackson of the Redesdale Archaeology Group (RAG) described the assemblage as “exceptional in both quantity and quality,” noting that the diversity of finds reveals the fort’s role as a hub of trade, craftsmanship, and daily life on the imperial frontier.

The artifacts—many remarkably well-preserved due to the site’s damp soil—illustrate a world of imported goods, sophisticated design, and cross-provincial connections. Pottery from Gaul and Spain, fine brooches with colored enamel, and weapon fragments from local workshops combine to tell the story of a multi-ethnic garrison integrated into the global Roman economy.

Unveiling Bremenium’s Hidden Past

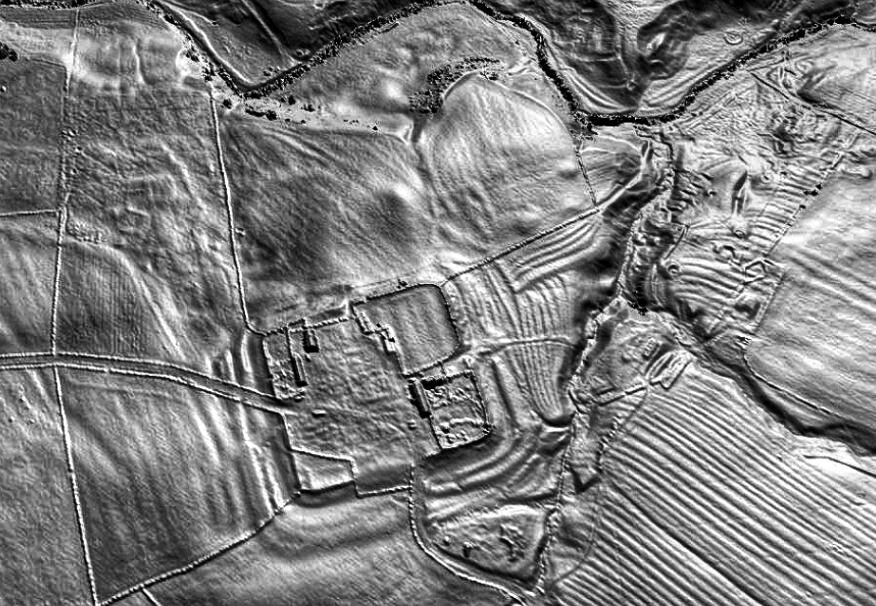

Ongoing research at Bremenium continues to transform understanding of Rome’s northern defenses. The fort’s strategic location on Dere Street made it a key staging post between York (Eboracum) and the forts of Scotland. Recent geophysical surveys have identified a civilian settlement (vicus) outside the fort walls, suggesting that families, traders, and craftspeople lived alongside the soldiers.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund, together with Newcastle University and RAG, has invested nearly £50,000 into this long-term project, enabling a blend of professional supervision and community participation that has become a model for public archaeology in the UK.

Following the success of the 2025 campaign, plans are already underway to return to Bremenium in 2026. Future excavations aim to investigate the fort’s gates, supply depots, and possible bathhouse remains. Researchers hope to uncover further evidence of cross-cultural interaction between Roman settlers and local Britons, deepening the narrative of a frontier that was not merely defensive, but dynamic and diverse.

A Gemstone Window into the Roman World

The two Bremenium intaglios are more than artistic curiosities—they are symbols of identity, migration, and belonging. Their discovery confirms that even at the cold, windswept edge of the empire, Rome’s soldiers maintained strong cultural ties to the Mediterranean world they left behind. Through these tiny masterpieces of craftsmanship, we catch a rare and personal glimpse into the lives, beliefs, and aspirations of people who once stood watch at the very limits of Roman civilization.

Cover Image Credit: A lidar view of Bremenium Roman fort, vicus, and camp in Northumberland. Dr John Wells – Wikipedia