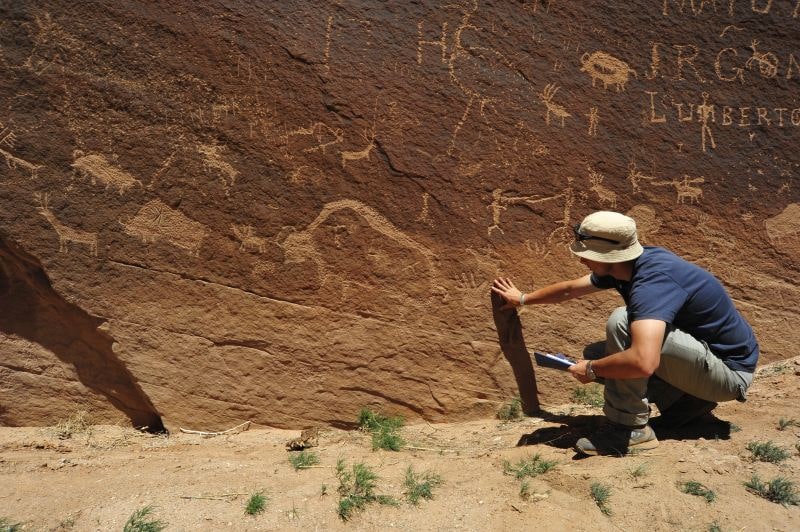

Archaeologists from the Jagiellonian University, southern Poland, have made a significant discovery of ancient indigenous paintings and carvings in the US state of Colorado-Utah border.

This Polish team has been exploring the area for over a decade, unraveling the mysteries of the 3000-year-old Pueblo culture.

Leading the research since 2011, Radosław Palonka, a professor at the Jagiellonian University and a specialist in New World archeology, says the findings dramatically alter the understanding of settlement in the area. His team is the only Polish and one of the few European archaeological groups to work in the region.

The research is carried out at the Castle Rock Pueblo settlement complex, located on the picturesque Mesa Verde plateau on the border between Colorado and Utah. These areas are popular not only with archaeologists but also with tourists, because of the famous Pre-Columbian settlements built in rock niches or carved into canyon walls as well as numerous works of rock art created by members of the ancient Pueblo culture, which dates back to nearly 3 thousand years ago and is still present almost exactly in the same area.

“The agricultural Pueblo communities developed one of the most advanced Pre-Columbian cultures in North America. They perfected the craft of building multistorey stone houses, resembling medieval town houses or even later blocks of flats. The Pueblo people were also famous for their rock art, intricately ornamented jewellery, and ceramics bearing different motifs painted with a black pigment on white background’,” Prof Palonka said.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

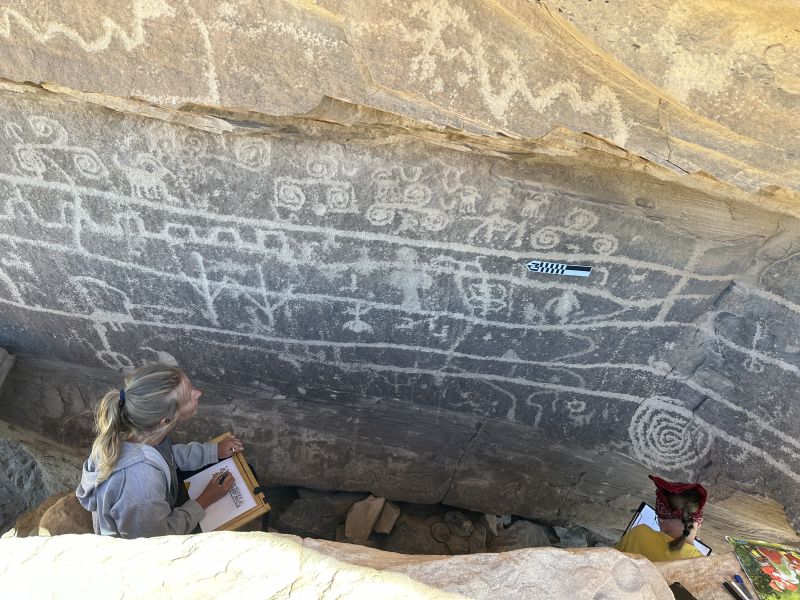

The discoveries of his team include previously unknown huge galleries and petroglyphs dated to various historical periods. The oldest of them, showing warriors and shamans, are estimated to date back to as early as the 3rd century AD, the period known as the Basketmaker Era. They were engaged in farming and produced characteristic baskets and mats. Most petroglyphs come from the 12th and 13th century.

These carvings vary in form, featuring complex geometric figures and spirals. The rock art frequently portrays shamans, warriors, bison, deer, and bighorn sheep, with some depicting hunting scenes.

In the 15th-17th century, when the area was inhabited by the Ute tribe, the rock panels started to feature large narrative hunting scenes showing bison, mountain sheep and deer hunts. In later centuries they also depicted horses, which reflected the events of the Spanish conquest, before which these animals were unknown to Native North Americans (they disappeared from this continent during the last ice age).

The newest pieces of rock art include the 1936 signature of Ira Cuthair, a famous cowboy, renowned not only in Utah or Colorado, but also in Arizona and New Mexico.

The discoveries were made in the higher, less accessible parts of three canyons: Sand Canyon, Graveyard Canyon, and Rock Creek Canyon, following hints from local residents.

Prof. Palonka’s research has resulted in the discovery of previously unknown petroglyphs 800 meters (2625 feet) above the cliff settlements, with spirals up to one meter in diameter. These petroglyphs, which were used for astronomical observations and calendar determinations in the 13th century, reshaped the understanding of population size and religious practices.

The Polish team anticipates further discoveries and awaits a detailed 3D map of the canyons, prepared by University of Houston researchers who conducted both LIDAR and optical surveys by flying 450 meters above the canyons.

The Polish archaeologists also work closely with local Native American groups such as the Hopi and Ute tribes, helping them understand the iconography and art of the indigenous people.

Next year, the team plans to record video interviews with tribal elders for a permanent multimedia exhibit at the Canyons of the Ancients Visitor Center and Museum, including the Kraków archaeologists’ findings.

Cover Photo: Jagiellonian University in Kraków