In the rose-red cliffs of Petra, water was never just a necessity. It was power, prestige—and engineering brilliance carved directly into sandstone.

A new archaeological survey has revealed that the city’s ‘Ain Braq aqueduct was far more technologically ambitious than scholars once believed. Hidden within a 2,500-square-meter sector of Jabal al-Madhbah, researchers identified not one but two separate conduit systems—built in different phases and using entirely different technologies. At the heart of the discovery: a rare 116-meter pressurized lead pipeline, an extraordinary feature in the eastern Mediterranean outside urban building interiors.

The findings significantly reshape our understanding of Nabataean hydraulic engineering during Petra’s peak in the first centuries BCE and CE.

Two Aqueducts, Two Technologies

Petra flourished as the capital of the Nabataean Kingdom before its incorporation into the Roman Empire and eventual decline after the earthquake of 363 CE. In a semi-arid environment, survival required mastery over water. Yet the city did more than survive—it supported baths, ornamental gardens, sacred water installations, and monumental complexes that demanded continuous, controlled supply.

The new survey shows that the ‘Ain Braq aqueduct operated in two major phases.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The earlier phase employed a pressurized lead pipeline—smooth, welded tubes capable of handling significant hydraulic pressure. Unlike the terracotta pipes commonly used in Nabataean systems, lead conduits could function as inverted siphons, allowing water to traverse steep terrain and rise before descending again. That technological choice suggests both technical sophistication and substantial financial investment.

At some point, however, the lead system was abandoned and sealed. In its place came a second network of open channels and terracotta pipes, laid over a carefully constructed stone substructure. These gravity-fed conduits directed water toward a small distribution box with two outlets, allowing controlled redistribution into different sectors of the city.

An economic decision? Almost certainly. Lead demanded raw material, fuel, specialized craftsmanship—and maintenance expertise. Terracotta was cheaper, familiar, and easier to repair.

But the initial installation of lead tells another story: Petra’s engineers were not merely practical. They were ambitious.

Supplying Power at Az Zantur

The lead conduit likely transported water uphill to the reservoir on Az Zantur, a strategically elevated ridge overlooking the city center. From there, gravity could distribute water efficiently to major urban complexes.

This was not random infrastructure. The chronology suggests the aqueduct may have been planned alongside monumental projects traditionally associated with the reign of Aretas IV, one of Petra’s most influential rulers.

During his era, Petra saw extensive urban expansion, including the construction of the Great Temple and the elaborate Garden and Pool Complex—structures that required steady water flow not only for functionality but for symbolic display. Flowing water in a desert capital projected control over nature itself.

No expense spared. No terrain too steep.

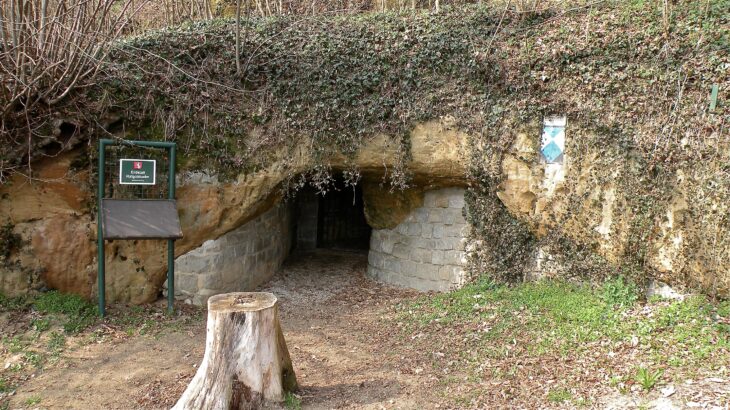

The Dam That Doesn’t Fit

Among the mapped structures was a large retention dam sealing a natural gap in the sandstone massif. Its appearance is unusual. The wall displays an irregular outline and a tiered, stepped face—features not commonly observed in other Petra dams.

At first glance, weathering may explain the uneven surface. Builders often coated dams with reddish plaster to blend them into the surrounding rock. Centuries of exposure could have stripped away those layers.

Yet the stepped form may have been intentional.

A broad base tapering upward would have reduced structural stress from the enormous pressure exerted by stored water. In a reservoir of substantial height, hydraulic force would have been immense. The stepped design could have distributed load while conserving material.

Or perhaps there was something more theatrical at play.

Petra is known for artificial waterfalls and controlled cascades integrated into its urban landscape. The dam’s tiered face may once have allowed seasonal rainwater to spill dramatically into a basin below—an engineered spectacle in a desert setting.

Function and aesthetics were not mutually exclusive here.

A Dense Hydraulic Landscape

The survey documented nine conduits in total, along with a large reservoir closed off toward the city by the high dam, two cisterns, and seven basins of varying sizes and functions. Numerous runoff channels carved into rock surfaces reveal a coordinated strategy for collecting and redistributing seasonal rainfall.

This was not a single aqueduct—it was a hydraulic ecosystem.

Earlier scholarship often reconstructed Petra’s water system on a macro scale, mapping general routes without close architectural documentation. By contrast, the recent micro-approach—focused on a tightly defined sector—has yielded concrete structural evidence that challenges simplified models.

Petra’s water management was layered, phased, and adaptive.

Rethinking Nabataean Innovation

Lead pipelines are rare in the Levant outside interior building contexts. Their presence in an external aqueduct corridor underscores a level of technological confidence that rivals Roman hydraulic achievements.

And yet the shift back to terracotta demonstrates something equally important: flexibility.

Petra’s engineers adjusted materials and methods over time, balancing performance with sustainability. The system evolved alongside the city itself.

In a landscape where rainfall was unpredictable and springs limited, water defined political authority and urban identity. The newly documented lead conduit—and the complex network surrounding it—offer tangible proof that Petra’s grandeur rested on invisible foundations beneath the sandstone.

Water made Petra possible.

And the engineering behind it continues to surprise.

Urban Development of Ancient Petra Project

Jungmann, N. (2025). Rediscovering the ‘Ain Braq aqueduct: new insights into Petra’s urban water management. Levant: The Journal of the Council for British Research in the Levant, 1–19. doi:10.1080/00758914.2025.2592501

Cover Image Credit: The Urn Tomb, Petra, Jordan – Wikipedia Commons