A finely carved lion-head stone spout has emerged from the soil of Bathonea, the ancient harbor city lying along Istanbul’s Lake Küçükçekmece, revealing not only artistic craftsmanship but also the industrial pulse of a Late Antique olive oil and wine workshop. The expressive sculpture—once channeling liquid through the lion’s open jaws into a fermentation pool—stands as a fusion of engineering precision and symbolic artistry rarely seen in production architecture.

Excavations led by Prof. Dr. Şengül Aydıngün of Kocaeli University, under the Heritage for the Future Project of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, have brought to light a large-scale complex equipped with pressing platforms, collection basins, storage units, and fragments of amphorae and glass cups. Together, these findings paint a vivid picture of an ancient facility where agricultural production, trade, and ritual practice once converged on the Thracian shore of the Marmara Sea.

Lion’s Mouth as Engineering and Art

The lion-head spout is the visual and functional heart of this workshop complex. Liquid—presumably wine or olive-byproduct—would flow from the carved lion’s mouth into a connected fermentation basin, indicating an intentional architectural integration of aesthetics and process. According to excavation director Prof. Dr. Şengül Aydıngün, the structure is “elegantly built” and underscores how the facility combined artistic craftsmanship with industrial scale expansion.

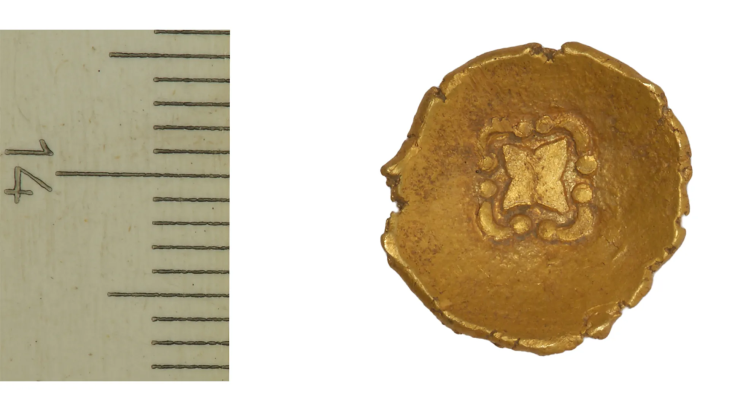

This is not the first known example of lion-head spouts in antiquity. In Pompeii, a tub bears a narrow side spout in the form of a lion’s head, channeling wine into an underlying dolium used in ritual or production contexts. Similarly, in Greek architecture, lion-head spouts frequently appeared as waterspouts or gutter ends—for instance, the Parthenon’s corner gutters sometimes terminated in lion heads. At the Metropolitan Museum, a 4th-century BCE bronze lion’s head spout, originally attached to a vessel, demonstrates the motif’s cross-use in both architecture and container fittings.

But the Bathonea example is especially notable for linking form with function in a production workshop rather than purely decorative or drainage contexts. The expressive sculpture—once channeling liquid through the lion’s open jaws into a fermentation pool—embodies the union of function and symbolism, echoing a visual language that stretched across the ancient Mediterranean. In both Greek and Roman art, the lion symbolized strength, divine protection, and royal power; in later Christian and Byzantine contexts, it came to represent vitality, resurrection, and solar energy. Its presence in a production setting at Bathonea suggests that the act of pressing oil or fermenting wine may have carried ritual connotations tied to abundance and divine favor.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Workshop Infrastructure: Pressing, Fermentation, Storage

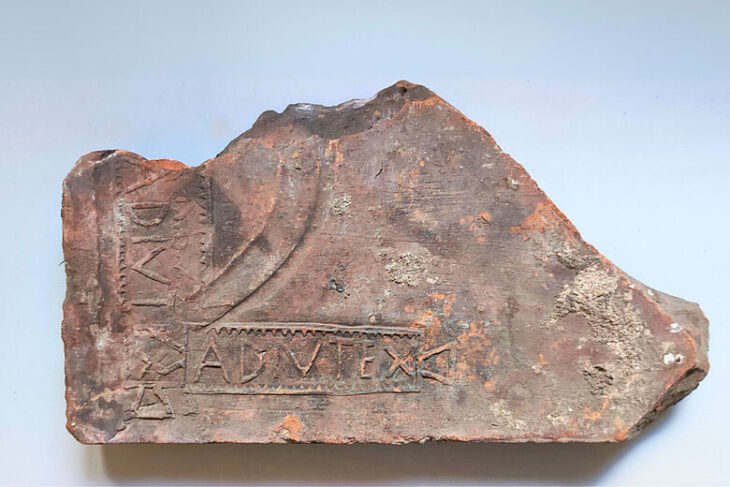

Beyond the lion’s spout, the excavation has revealed a full olive oil and wine production complex: pressing platforms, collection basins, fermentation pools, and storage units. Amphora fragments, sometimes inscribed with producer or harvest data, and glass drinking cups—likely used on-site for quality testing or sampling—were also recovered. The convergence of utilitarian and symbolic elements implies that the workshop served both economic and social or ritual roles.

One of the more provocative finds is the presence of animal bones in one of the pools, hinting at ritual depositions concurrent with industrial use. Aydıngün suggests that the site may have been a junction between manufacturing, storage, and ceremonial consumption.

Bathonea in Context: A Port Settlement with Layers of History

Bathonea lies about 20 km west of Istanbul proper, on the European shore of what is today Lake Küçükçekmece. Though often described in the media as a “lost city,” the name Bathonea itself is not attested in historical sources; it is a provisional designation based on hydronyms and regional toponyms.

Excavations at the site—conducted jointly by the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism and Kocaeli University under Aydıngün’s supervision—have unearthed two harbors (a “Large” and “Small”), an ancient lighthouse (one of the few in Turkey beyond Patara), mosaic-floored palatial complexes, underground water channels, and city walls. Stratigraphic layers suggest continuous occupation from Hellenistic through Late Roman/Byzantine periods.

There have also been sensational claims of Viking or Varangian presence in Bathonea—amber crosses and Norse artifacts have been reported. Though intriguing, these finds remain debated and are yet to be fully contextualized within the broader stratigraphy.

The region is also seismically active, and some structural damage in excavated buildings may reflect historic earthquakes in the 6th, 10th, or 11th centuries.

Implications & Future Prospects

The lion-head spout alone elevates this discovery beyond a simple industrial site—they suggest symbolic, aesthetic, or even ritual intentions embedded in production architecture. The juxtaposition of factory components with ornate sculptural elements invites rethinking of how communities integrated utility and meaning.

Furthermore, the discovery supports the idea that coastal Thrace and the Marmara region remained actively engaged in wine and olive oil production into Late Antiquity, not just as subsistence but as trade goods tied to maritime networks.

As excavation continues, subsequent seasons may expose more lion-spouts or variation in design—offering comparative material to trace regional stylistic exchange. Also awaiting further work are inscriptions on amphora fragments, which could reveal producer names, appellations, or trade relations.

Finally, the Bathonea complex helps fill a gap in our understanding of peripheral production hubs that serviced the metropolis of Constantinople, serving both regional demand and possibly export markets through the port infrastructure.

Cover Image Credit: DHA