In a discovery that is already rewriting the history of Japan’s ancient Kofun period, researchers have confirmed the existence of two rare burial artifacts from the Emperor Nintoku Tomb, Japan’s largest and one of its most mysterious imperial burial mounds. The find marks the first time physical grave goods from the UNESCO World Heritage site have been verified, more than 150 years after they were believed lost.

Officials from Sakai City and the Kokugakuin University Museum announced on June 19 that the items—a gold-plated small knife (tōsu) and fragments of gilt armor—originated from the Daisen Kofun, the massive keyhole-shaped mound in Osaka traditionally attributed to Emperor Nintoku (reigned early-to-mid 5th century).

Hidden for Over a Century

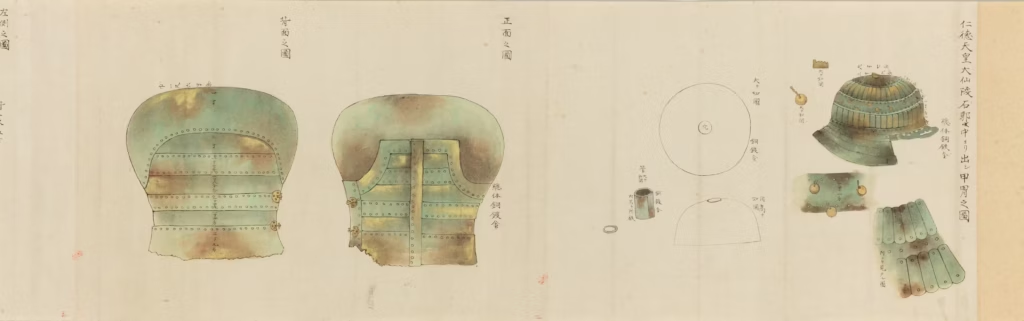

The artifacts were traced back to the first documented opening of a burial chamber in 1872 (Meiji 5), when a landslide exposed part of the mound’s front section. The investigation was led by Kaichiro Kashiwagi (1841–1898), a master builder, art collector, and early cultural preservationist, who sketched detailed illustrations of the tomb’s grave goods before they were reportedly reburied.

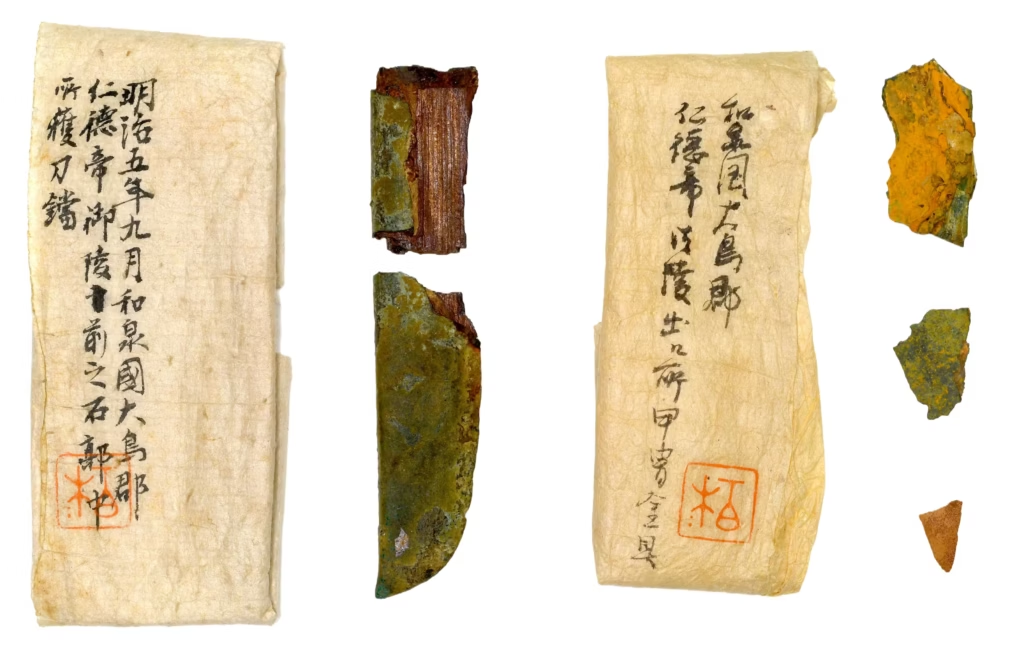

For more than a century, these illustrations were considered the only record of the items. However, the newly recovered knife and armor pieces were found in the personal collection of Takashi Masuda, founder of Mitsui & Co. and a prominent art patron who had close ties to Kashiwagi. The objects were acquired last year by Kokugakuin University from an art dealer, still wrapped in paper bearing Kashiwagi’s seal and handwritten notes describing their origin.

Unique Fifth-Century Craftsmanship

Scientific analysis revealed the knife’s wooden sheath—made from Japanese cypress—was encased in a gold-plated copper plate and secured with silver rivets. The iron blade is broken into two sections, measuring 6.9 cm and 3.7 cm, suggesting an original length of around 15 cm. Experts believe it was ceremonial rather than functional, noting that no other gold-plated small knives from fifth-century kofun burials have been documented.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The armor fragments, measuring 3–4 cm, are made of iron coated with gold rather than the gold-plated copper once assumed from historical drawings. This revision underscores how modern materials science can refine our understanding of ancient craftsmanship.

According to archaeologist Taro Fukazawa of Kokugakuin University, “These are not everyday weapons. They were likely created specifically as burial offerings for the ruling elite, showcasing the extraordinary political and economic power of the Nintoku court.”

A Tomb of Unparalleled Scale

The Daisen Kofun—also known as the Emperor Nintoku Mausoleum—is the largest keyhole-shaped burial mound in Japan, measuring 486 meters long and 34 meters high, surrounded by three moats. It forms part of the Mozu–Furuichi Kofun Group, inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019 for its exceptional testimony to the culture of the Kofun period (3rd–6th centuries).

Though long attributed to Emperor Nintoku, the true occupant remains unconfirmed. The Imperial Household Agency strictly controls access, allowing only limited, non-invasive surveys. This secrecy has fueled debate among historians and archaeologists.

Emperor Nintoku: The Legendary Sovereign

Emperor Nintoku, traditionally listed as Japan’s 16th emperor, is remembered in historical chronicles for his benevolence and reforms. Legends recount that he suspended tax collection for three years after observing the hardship of his people, a gesture that became emblematic of just leadership. While the historical accuracy of such tales remains uncertain, his reign is associated with a period of consolidation of imperial authority and expansion of statecraft.

The sheer size and lavishness of the Daisen Kofun—and the exceptional craftsmanship of its newly discovered grave goods—reflect the centralization of power during his era.

Significance for Future Research

Until now, scholars relied solely on 19th-century illustrations to study the tomb’s burial offerings. The physical recovery of artifacts opens the door to modern analyses, including metallurgical testing and manufacturing techniques, that could reveal more about trade, technology, and ritual practices in ancient Japan.

The recovered items will be publicly exhibited for the first time at the Sakai City Museum from July 19 to September 7, alongside Kashiwagi’s original drawings. Given their rarity, experts predict they will become central reference points in future Kofun period studies.

“This is more than a spectacular archaeological find,” said museum deputy director Takashi Uchikawa. “It’s a tangible link to one of Japan’s most enigmatic rulers and a reminder of the artistry and political might of the ancient Yamato court.”

With the artifacts now secured, researchers and the public alike have a rare opportunity to glimpse the opulence of an emperor’s final resting place—an opportunity denied for over a century.

Cover Image Credit: Daisen-Kofun, the tomb of Emperor Nintoku, Osaka. Public Domain