Human sacrifice was not just a ritual act in Neolithic China—it was a carefully engineered system, and nowhere is this clearer than in the ancient city of Shimao. What genetic research has now revealed is both startling and unprecedented: men and women were sacrificed for entirely different reasons, in different places, and for different social purposes. This discovery, uncovered by DNA taken from nearly two hundred individuals, exposes a civilization where death itself was divided by gender, shaping the political and spiritual identity of one of prehistoric China’s most enigmatic cities.

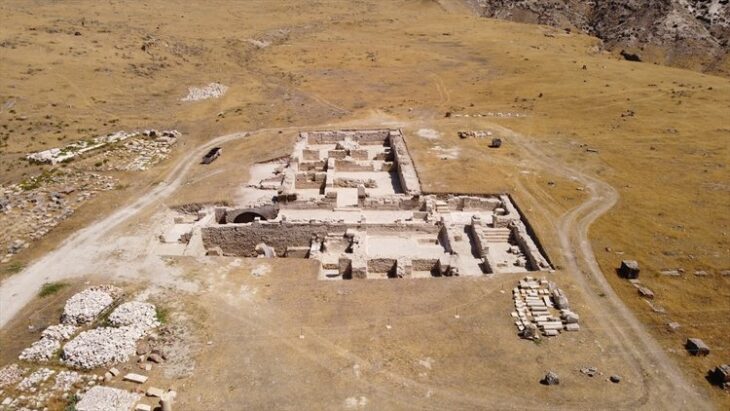

When archaeologists first uncovered the sprawling stone ruins of Shimao, a monumental Neolithic city rising from the northern edge of China’s Loess Plateau, they knew they had found something extraordinary. Towering fortifications, layered terraces, and carefully organized urban districts hinted at an early experiment in statehood—one that emerged a thousand years before the first Chinese dynasties. But it was only when scientists turned to ancient DNA that Shimao revealed its most startling truth: in this society, even death followed strict gender lines.

A new genomic study analyzing 169 ancient individuals has uncovered a deeply gendered ritual landscape at Shimao, where men and women were sacrificed for different purposes and in different places. This discovery not only overturns earlier assumptions about who the victims were but also exposes a complex social system built on lineage, hierarchy, and symbolic acts of power.

The Gate of Skulls: A Ritual Meant for Men

For decades, scholars believed that the victims found in Shimao’s infamous mass burials—most notably the cluster of over 80 skulls beneath the East Gate—were largely women. Morphological assessments seemed to support this idea, and it fit neatly into what was known about later periods of Chinese ritual practice. But genetics told a very different story. DNA revealed that almost all individuals sacrificed at the East Gate were men, radically shifting interpretations of the rituals that shaped life and death in the city.

These men were not buried alongside elite families or placed in honorific tombs. Instead, they were interred at the threshold of the city—its gate, its symbolic point of entry and defense. This suggests their deaths may have been connected to communal or construction rituals, perhaps intended to fortify the settlement spiritually or mark major building phases. Scholars note that similar practices appear in later historical periods in China, where foundational sacrifices were believed to protect structures or sanctify urban space. The Shimao findings now push these traditions back thousands of years earlier than previously documented.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Within the Walls: Women as Companions to the Elite Dead

Inside the walls, however, a contrasting pattern emerged. In the elite cemeteries at Huangchengtai at the city’s center and Hanjiagedan to the south, the sacrificial victims were overwhelmingly women. They were placed beside high-status tomb owners—noble figures buried with ornate goods and signs of political authority. These rituals were not large, public events. Instead, they were intimate, carefully arranged acts associated with lineage, ancestry, and the maintenance of elite identity.

DNA analysis showed that these sacrificed women were not related to the nobles they accompanied. They also did not seem to belong to the same biological communities. This suggests that they were brought into Shimao from outside—perhaps through marriage exchanges, alliances, or as part of tribute systems tied to the city’s influence. The contrast is striking: men sacrificed at the gates in collective rituals, women sacrificed within elite tombs in private, status-enhancing ceremonies.

Kinship, Power, and a Patrilineal Order

These gendered patterns reflect a wider social structure uncovered by the genomic data. Shimao was a strongly patrilineal society, where male lineage determined status, inheritance, and burial privilege. Across generations, male tomb owners carried the same paternal genetic markers, indicating stable family lines that formed the backbone of Shimao’s ruling class. In contrast, female elites showed diverse maternal lineages, consistent with female exogamy—the practice of bringing women into the community from elsewhere, a strategy common in early hierarchical societies seeking political alliances and genetic diversity.

But Shimao was far from isolated. DNA revealed that while its people descended largely from earlier Yangshao culture groups in northern China, they also had connections stretching south toward rice-farming populations and north toward the Yumin pastoralists of Inner Mongolia. These links suggest extensive interaction across the region, even if the city maintained a distinct and tightly controlled internal hierarchy.

A Society Where Rituals Wrote the Rules

What emerges from this research is a portrait of a society in transition—urbanizing, increasingly stratified, and experimenting with forms of political authority that relied on symbolic ritual. Human sacrifice, although disturbing by modern standards, appears to have been a socially embedded practice that reinforced class distinctions and ritual obligations. In Shimao, these practices were not random or chaotic. They were organized, consistent, and shaped by gender.

The men at the gate and the women beside the elite tell two halves of the same story. They reveal a society where public rituals and private funerary rites played different roles, where gender determined one’s place not only in life but also in death, and where the emerging logic of early statehood was being written into the landscape through bodies, ancestry, and belief.

Although much about Shimao remains unknown—including the exact meanings its inhabitants attached to these rituals—the new genetic evidence marks a turning point. It allows researchers to move beyond artifacts and architecture and see the lived human realities behind one of prehistoric China’s most enigmatic cities.

The Legacy of a Gendered Deathscape

The study’s authors hope further investigation will illuminate how power, kinship, and identity intersected at this early stage of East Asian state formation. For now, the revelations from Shimao offer a rare glimpse into a world where gender shaped not only daily life but also the final journey into death—a world in which the gates were guarded by sacrificed men, and the dead elite were escorted into eternity by sacrificed women.

Chen, Z., Gardner, J.D., Sun, Z. et al. Ancient DNA from Shimao city records kinship practices in Neolithic China. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09799-x

Cover Image Credit: Shimao east gate and decorated wall (circa 2000 BCE). Wikipedia