Rising once above the seventh hill of Constantinople like a carved chronicle in stone, the Column of Arcadius—known in Turkish as Arkadyos Sütunu or Avrat Taşı—was more than a monumental victory marker. In the centuries after its construction, it became the subject of folklore, miracle tales, and Ottoman–era curiosity. Among the most striking of these stories are those transmitted by the 17th-century traveler Evliya Çelebi, who recorded popular legends describing the stone as possessing mystical qualities. In these accounts, a fairy-maiden statue atop the monument was said to come to life once a year, causing the birds in the sky to fall to the ground, thereby feeding the people of the cityBlending myth with memory, the Column of Arcadius stands at the crossroads of archaeology, legend, and urban identity.

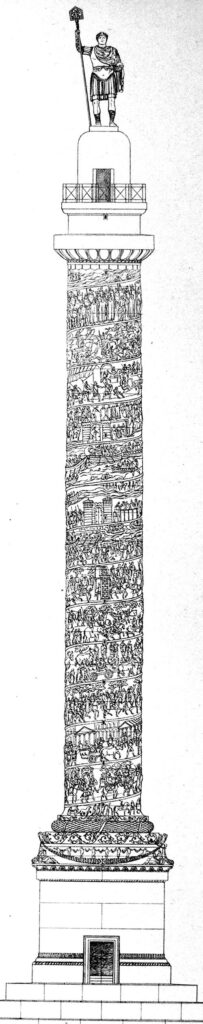

Built in 401 CE to commemorate Emperor Arcadius’s victory over the Gothic forces led by Gainas (399–401), the column once dominated the Forum of Arcadius on the hill of Xerolophos (Kserolofos), just south of the Lycus Valley—today’s Bayrampaşa Deresi. The monument was completed only in 421, during the reign of Arcadius’s successor Theodosius II, and at nearly 40 meters tall it rivaled the Columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius in Rome. Its shaft was wrapped in a spiraling frieze illustrating campaigns, triumphs, military processions, and imperial ceremony, while an immense statue of Arcadius crowned the summit—accessible via an internal spiral staircase.

Time, however, was rarely kind to Constantinople’s monuments. The column was damaged by earthquakes in 543, 550, and again in 704, when the colossal equestrian statue added by Theodosius II is said to have fallen. Yet even as it fractured and weathered, the monument refused to vanish from the city’s imagination. During the Ottoman era, the base of the column stood beside a marketplace known as Kadınlar Pazarı, earning its popular name “Avrat Taşı” (Women’s Stone). It was here that Evliya Çelebi described the column in his Seyahatname, not only as an ancient remnant but as an object of popular mysticism.

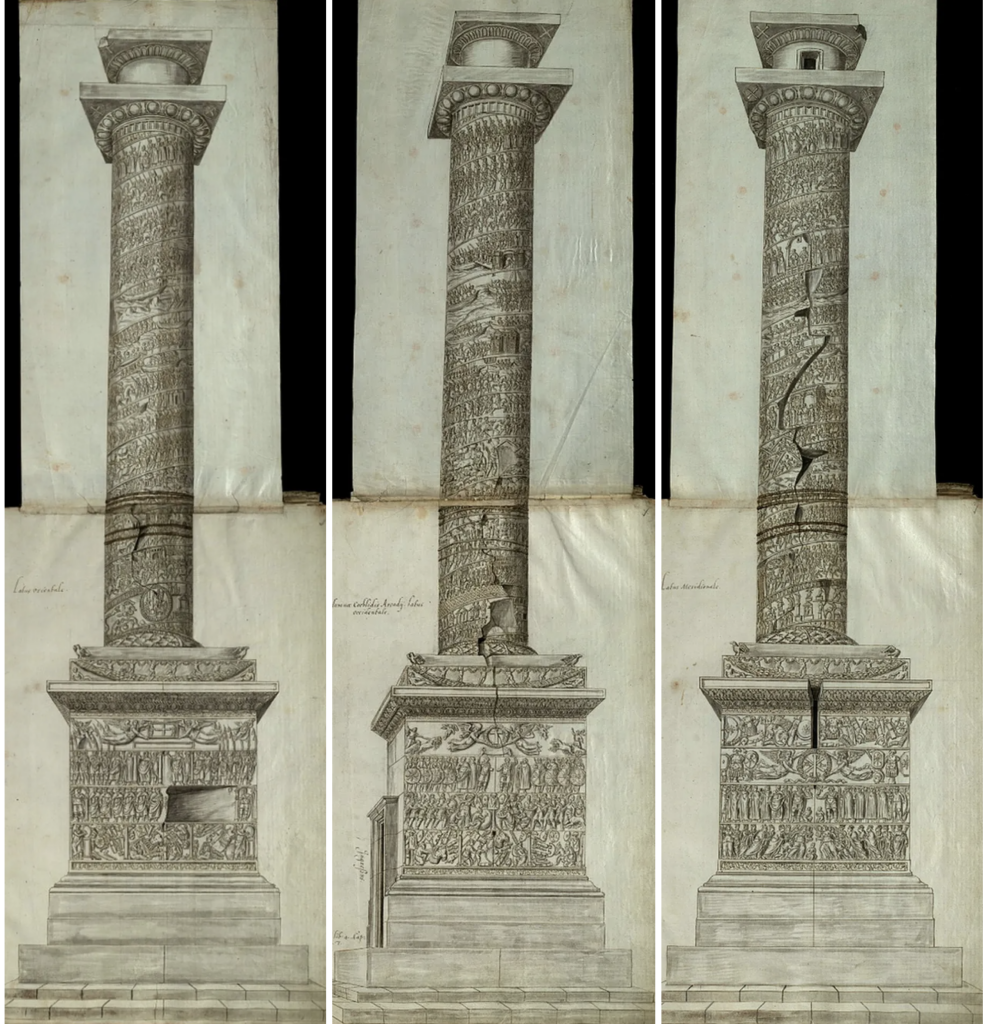

From left to right: the east, west, and south faces of the Column of Arcadius. Freshfield Album (1574), Trinity College, Cambridge

According to Çelebi, a tremor on the day of the Prophet Muhammad’s birth cracked the column, yet—miraculously—it did not collapse. More captivating still was the legend of the fairy maiden statue that once stood in the small structure above the monument. Once each year, said the tale, the maiden would come to life; when she spread her arms, birds flying above the city fell gently to the ground, providing enough food to feed the poor of Istanbul. In this folklore, the Column of Arcadius became not simply a relic of imperial glory, but a benevolent guardian of the city, a stone miracle that nourished the people in times of hunger.

These stories do more than entertain—they reflect the way memory, myth, and architecture intertwined in Istanbul’s urban culture. To the Ottomans, the city’s Byzantine past was not a silent ruin but a living landscape full of secrets, talismans, and spiritual meanings. Çelebi’s account shows how the people of his time re-imagined classical monuments through the lens of faith and wonder, transforming an imperial triumph column into a symbol of divine protection and abundance.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Travelers and scholars across centuries also left detailed testimonies of the column’s physical grandeur. The French traveler Pierre Gilles measured and described it in the 16th century, laying foundations for modern archaeological study. Lambert de Vos’s detailed drawings in the 1570s—preserved in the Freshfield Album—offer rare visual records of the pedestal’s rich reliefs, depicting captives, victories, senators, soldiers, and personifications of cities. Later observers such as Robert de Dreux and Aubry de La Motraye recorded the monument’s increasingly fragile state; the latter reported that it was finally demolished after his departure in 1711 to prevent collapse. Archival evidence suggests that the structure stood until the early 18th century, possibly succumbing to an earthquake in 1719.

Today, only the massive masonry base of the Column of Arcadius survives, tucked into a courtyard on Haseki Kadın Sokak in Istanbul’s Cerrahpaşa neighborhood—its west face still visible from the street. Fragments believed to have belonged to the monument, including a sculpted block dredged near Davutpaşa in 1874, are preserved at the Istanbul Archaeology Museums. Scholars continue to emphasize the column’s role as a key example of late Roman imperial art, echoing the traditions of earlier triumphal monuments while projecting the message of unity between Arcadius and his co-emperor brother Honorius.

Yet the site’s power lies not only in art history. The Column of Arcadius—the Roman column that “fed” Istanbul in legend—embodies the layered spirit of the city itself. It reminds us that monuments are not merely stones but storytellers. They survive as anchors of memory, reshaped by every generation that lives among them. The fairy maiden who fed the hungry may never have stepped from the stone, but through centuries of storytelling she ensured that this fragment of a vanished forum remains alive in the city’s cultural imagination.

As conservation advocates call for better protection and urban planning around the surviving base, the Column of Arcadius invites both visitors and residents to look again—beyond the traffic and apartment walls—to glimpse a world where empire, myth, and community converge. In that sense, its most enduring legacy is not the victory it commemorated, but the stories it continues to inspire.

Source: Bauer, Franz Alto (1996). Stadt, Platz und Denkmal in der Spätantike: Untersuchungen zur Ausstattung des öffentlichen Raums in den spätantiken Städten Rom, Konstantinopel und Ephesos (in German). Mainz: P. von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-1842-6.

Croke, Brian ‘Count Marcellinus and his Chronicle‘, 2001

Wolfgang Müller-Wiener. Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Tübingen, 1977 s. 250-253

Sodini, Jean-Pierre “Images sculptées et propagande impériale du IVe au VIe siècle: recherches récentes sur les colonnes honorifiques et les reliefs politiques à Byzance”. Byzance et les images, La Documentation Française, 1994 s.43-94

Strzygowski, J. (1893) “Die Säule des Arcadius”, Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, VIII. s. 230-249

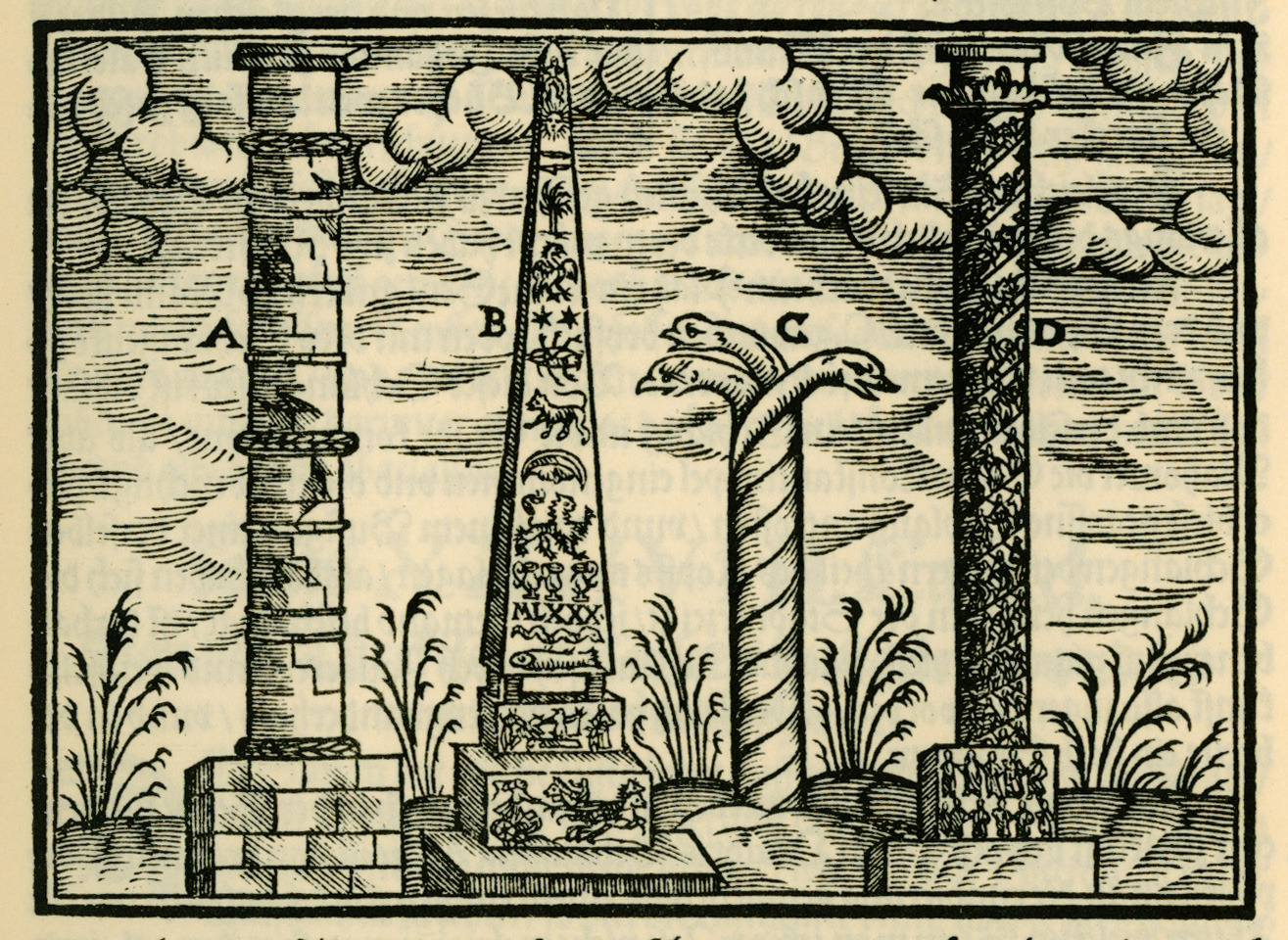

Column of Constantine, Obelisk of Theodosius, the Serpent Column, Column of Arcadius – Salomon Schweigger, Constantinople. Credit: Public Domain