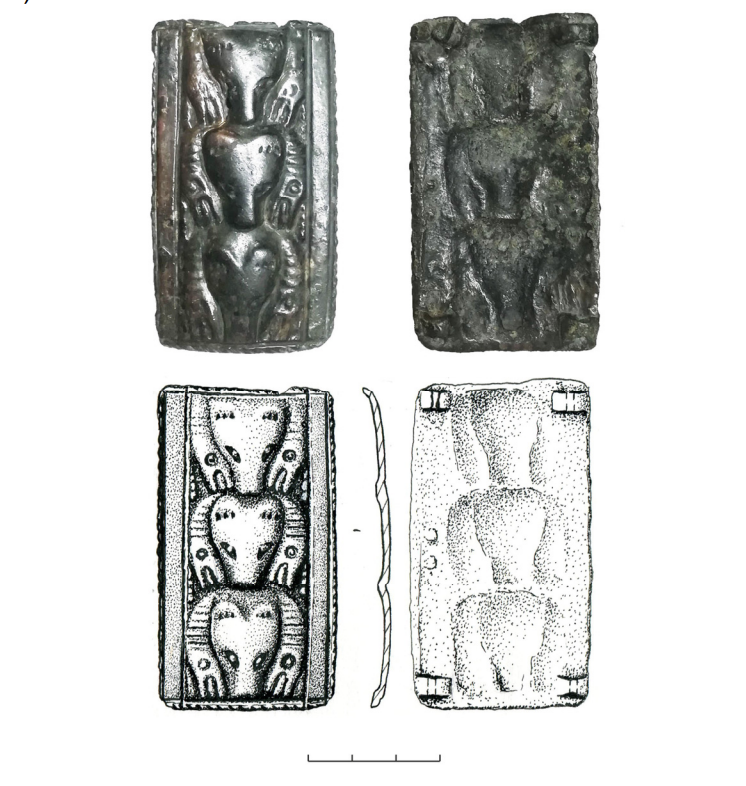

More than thirteen centuries after it was placed in the ground, a bronze plaque depicting bears in a sacrificial pose has resurfaced in the forest-steppe of southern Siberia.

Along the quiet banks of the Chumysh River in southern Siberia, archaeologists have uncovered a small bronze object that speaks to a much larger story—one of cultural encounter, adaptation, and identity at the edge of empires.

The artifact, a rectangular bronze plaque bearing the striking image of three bears arranged in a ritual pose, was recovered from an early medieval burial ground in the Altai region of Russia. Dated to the seventh or early eighth century AD, the plaque is now being recognized as one of the southernmost examples of a powerful symbolic tradition that once stretched across the forests of northern Eurasia. Its discovery is reshaping how scholars understand cultural interaction during the formative centuries of the Turkic world.

A Borderland Long Overlooked

The burial ground, known as Chumysh-Perekat, lies in northeastern Altai Krai, where open forest-steppe gradually gives way to the taiga landscapes of the Salair Ridge. This transitional zone has long remained archaeologically understudied, overshadowed by the monumental sites of the Altai Mountains to the south and the river cultures of western Siberia to the north.

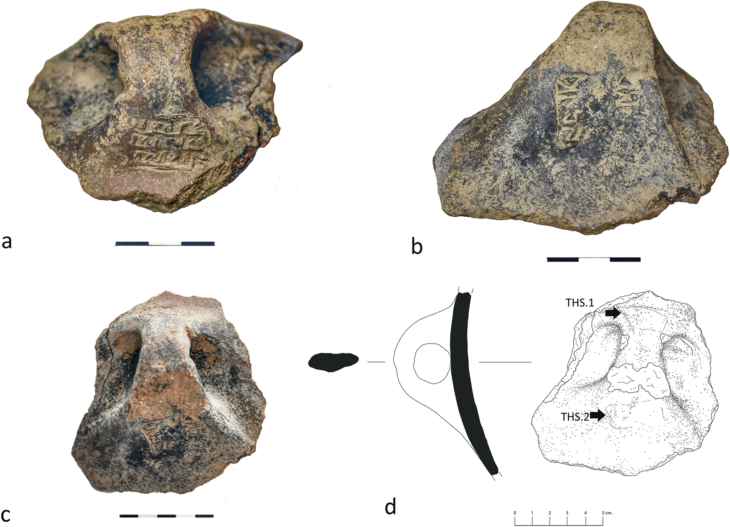

That began to change when erosion exposed human bones along the riverbank, prompting systematic excavations between 2014 and 2019 by researchers from the Institute for the History of Material Culture of the Russian Academy of Sciences and Altai State University. What they uncovered was a rare stratified cemetery containing burials from the Neolithic through the early Middle Ages—a compressed archive of thousands of years of human presence.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Among the most valuable finds were seventeen early medieval graves that had largely escaped looting. In the forest-steppe Altai, intact burials from this period are exceptionally rare, making Chumysh-Perekat a key site for reconstructing life on the northern margins of the Turkic Khaganates.

The Woman and the Bears

The bronze plaque was discovered in one of these graves, belonging to a woman estimated to have been between 35 and 50 years old at the time of her death. Although the burial had been disturbed in antiquity, most of the grave goods remained in place, suggesting a ritual intrusion rather than ordinary robbery.

The plaque depicts three bear heads positioned vertically, each framed by forelegs folded beneath the body—a configuration archaeologists describe as a “sacrificial pose.” Similar bear plaques are well known from the taiga and forest zones of western Siberia, where bear symbolism formed the core of hunting cults and cosmological beliefs among Ugric and other northern peoples. Until now, however, such objects were virtually unknown this far south.

Its presence here is therefore extraordinary—not only geographically, but culturally.

Northern Symbols, Southern Dress

What makes the burial especially revealing is the context in which the plaque appeared. The woman was adorned with jewelry and belt fittings typically associated with southern nomadic traditions, including pseudo-kolts—ornamental pendants linked to early Turkic costume—and elaborately decorated belt plaques.

These southern elements have close parallels in the Altai Mountains and Tuva, regions historically tied to the rise of early Turkic polities. Yet the bear plaque belongs firmly to a northern symbolic world. Their coexistence in a single burial reflects not simple trade, but a deeper cultural synthesis.

In other words, this was not a foreign object placed into a local grave by chance. It was part of a lived identity that combined traditions from multiple cultural spheres.

Adopting, Not Imitating

This pattern repeats across the cemetery. Several male burials were accompanied by horses—a hallmark of Turkic funerary ideology—yet the animals were placed in the graves in segmented form, a departure from canonical steppe practices. Similarly, ornate belts, typically markers of male warrior status among nomads, appear here in women’s and even children’s burials.

Such adaptations suggest that local forest-steppe communities were not passively absorbing Turkic customs. Instead, they were selectively reinterpreting them, fitting new ideas into existing social and ritual frameworks.

The result was a hybrid cultural landscape—one in which Samoyedic, Ugric, and Turkic elements overlapped rather than replaced one another.

A Dialogue at the Edge of Empire

The bear plaque itself embodies this dialogue. Bears held profound spiritual significance in northern Eurasia, often associated with ancestry, protection, and cosmic order. That symbolism endured even as Turkic political influence expanded northward during the seventh century.

Rather than erasing older beliefs, the advance of nomadic culture appears to have created spaces of negotiation, where identities were reshaped at the margins of imperial power.

Chumysh-Perekat offers a rare archaeological snapshot of that process in motion.

What Comes Next

Researchers are now analyzing organic materials recovered from the graves, including fragments of leather, wool, and silk textiles. Planned genetic studies aim to clarify biological relationships within the burial community and trace their broader origins.

Together, these investigations may help answer a lingering question: who were the people living between taiga and steppe during the age of Turkic expansion—and how did they see themselves?

For now, a single bronze plaque with three silent bears has opened a window onto a forgotten cultural conversation, carried out more than thirteen centuries ago along a quiet Siberian river.

Fribus, A. V., & Grushin, S. P. (2025). Between taiga and steppe: A new find of a plaque depicting “bears in a sacrificial pose” from the Upper Ob region. Vestnik of Archaeology, Anthropology and Ethnography, 1(68), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.20874/2071-0437-2025-68-1-6

Cover Image Credit: Grave 30 at the Chumysh-Perekat cemetery, Early Medieval Altai. Photo by Alexey Fribus.