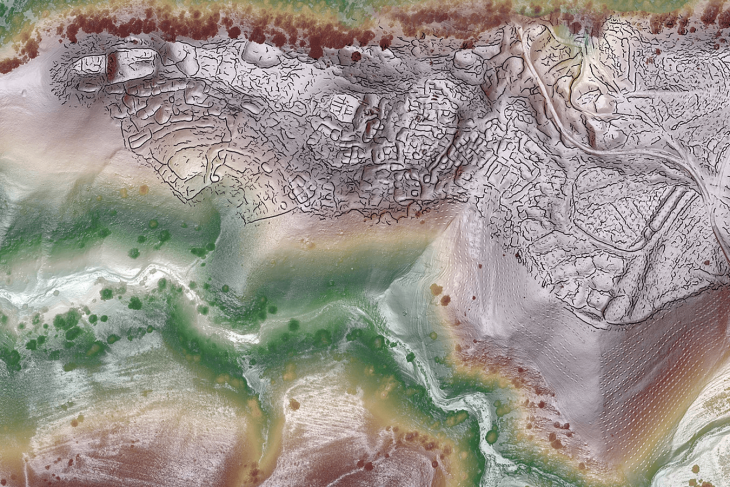

Archaeologists working in Karahantepe, one of the major sites of the Taş Tepeler (Stone Hills) Project in southeastern Türkiye’s Şanlıurfa province, are revealing an extraordinary picture of early human life. Recent excavations have uncovered more than 30 dwellings that belonged to one of the world’s earliest settled communities — a discovery that redefines our understanding of how people lived, worked, and ate over 11,000 years ago.

Led by Professor Necmi Karul of Istanbul University, the Karahantepe Project is transforming the site from a mysterious Neolithic sanctuary into a vibrant prehistoric neighborhood. The newly unearthed homes provide a tangible link between monumental ritual structures and everyday domestic life, showing that the people who built symbolic pillars were also family members, craftspeople, and early farmers.

A Village Beneath the Earth

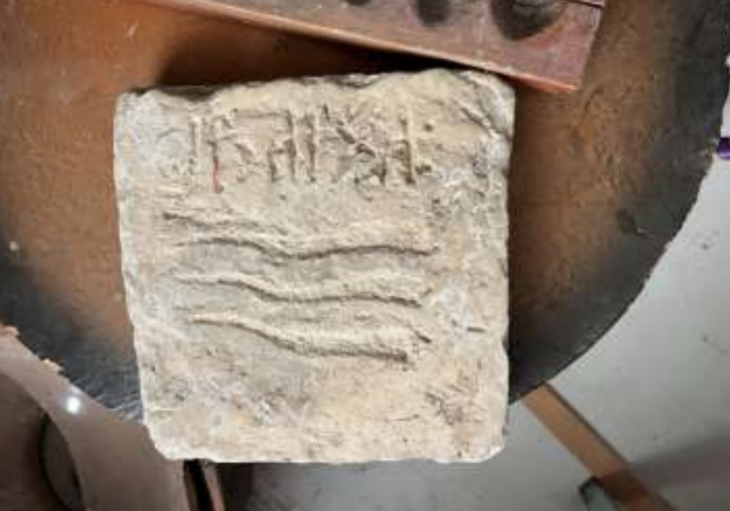

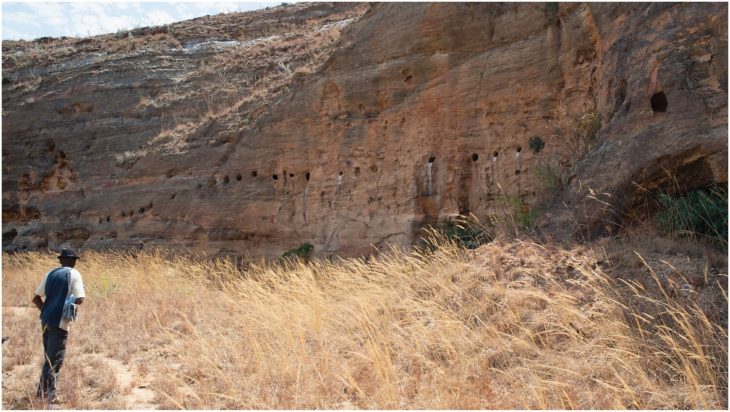

What makes Karahantepe truly remarkable is its network of subterranean houses. Each dwelling was carved partially or entirely into the bedrock, forming a dense, interconnected cluster that once formed the heart of the settlement.

According to Prof. Karul, the excavated houses vary in size from 3 to 6 meters in diameter and are arranged in a honeycomb-like pattern. The walls are irregular and oval rather than geometric — an organic form reflecting early experimentation with architectural space. Inside, archaeologists have found stone floors, hearths, storage compartments, and grinding platforms, all preserved remarkably well beneath layers of intentional backfill.

“These were not temporary shelters,” Karul explained. “They were built to last, designed for protection, food preparation, and social interaction. The layout tells us how early humans organized their daily lives within a shared environment.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Living Spaces with Symbolic Meaning

Although smaller than the monumental enclosures of nearby Göbeklitepe, the Karahantepe houses carry their own symbolic significance. Standing stones placed inside some huts suggest that the domestic sphere also had a spiritual dimension. When the houses were eventually abandoned, their interiors were filled with soil and their pillars deliberately toppled, a ritual act that may have marked the end of habitation or the passing of a generation.

The team is currently restoring many of these fragmented stones and wall sections, allowing researchers to reconstruct the settlement’s original layout. This process is helping scientists visualize how early communities blended sacred and domestic architecture — a duality that defines the Neolithic revolution in Anatolia.

A Snapshot of Daily Life

The physical organization of these houses reveals much about daily routines. The presence of hearths points to cooking and warmth as central activities. Stone platforms and flat grinding tools found within the dwellings suggest spaces dedicated to food preparation. Small alcoves carved into the rock likely served as storage areas for tools, grains, or dried plants.

These findings show that Karahantepe’s inhabitants were not only monument builders but also pioneers of domestic life. They lived in compact, efficient spaces — protected underground chambers that maintained a steady temperature year-round. The dense clustering of houses implies a closely knit community, where cooperation and shared labor were essential for survival.

Tracing What They Ate

The investigation of Karahantepe’s dwellings extends beyond architecture into the microscopic traces left behind on their floors and tools. Soil samples taken from inside the houses are being analyzed to uncover residues of plants and food remains.

Karul explained that his team uses a method called flotation, in which soil is mixed with water to separate small plant particles that cannot be seen by the naked eye. “Through this process, we can determine what kind of plants were processed, where food was prepared, and which spaces served for storage or consumption,” he said.

The results so far indicate the processing of wild grains and legumes, which may represent the early stages of plant domestication — a cornerstone of the transition from hunter-gathering to agriculture. The grinding stones uncovered inside the dwellings are especially crucial for this research, as they preserve microscopic residues that reveal what types of plants were ground and consumed.

Homes as Mirrors of Social Evolution

In contrast to the purely ceremonial atmosphere of Göbeklitepe, Karahantepe’s dwellings highlight the domestic roots of civilization. They demonstrate how early humans moved beyond collective ritual to establish stable households and defined living spaces.

These underground homes are more than just archaeological structures; they are evidence of social organization, where shared food, work, and belief systems gave rise to a new form of community. “By studying these houses,” Karul said, “we are studying the very beginning of human society — the moment when people first began to live together permanently.”

A New Perspective on the Stone Hills

The discoveries at Karahantepe add a powerful new chapter to the story of the Taş Tepeler region. They reveal that beneath the monumental pillars and carvings lay a thriving domestic world — one filled with warmth, food, and cooperation.

By focusing on these early homes, archaeologists are able to see how architecture, environment, and diet combined to shape human experience in the Neolithic era. Each stone floor and grinding tool tells a story not only of survival but of the human desire to build, share, and belong.

As ongoing analyses continue to uncover traces of meals once prepared and fires once lit, Karahantepe stands as one of the earliest known examples of a true community — a place where the world’s first settlers began to transform survival into civilization.