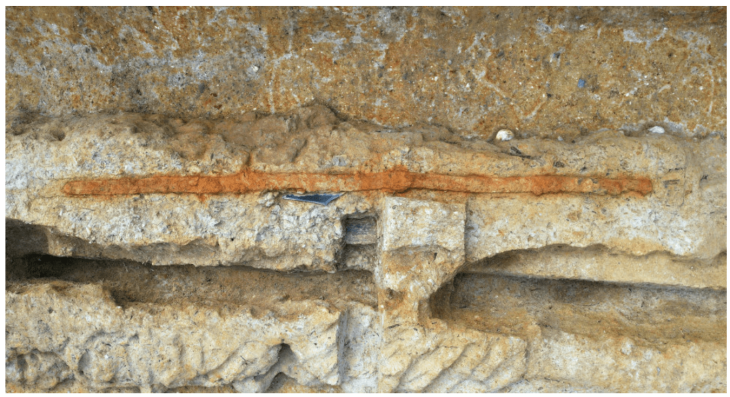

A newly uncovered monumental burial mound in the Swiss canton of Fribourg is rewriting what researchers know about social hierarchy and ritual landscapes in the western Alps during the early Iron Age. The discovery—announced by the Amt für Archäologie des Kantons Freiburg (AAFR)—reveals a remarkably well-preserved grave dating back roughly 2,600 years, and offers a rare window into the lives of influential individuals who shaped the Intyamon Valley around 600 BCE.

A Race Against Time in the Intyamon Valley

The excavation site lies in Grandvillard, a village in the Gruyère district, where archaeologists have been uncovering traces of an Iron Age burial ground since 2019. The newly exposed mound measures approximately 10 meters in diameter and encloses a single central burial, now nearing full excavation.

But the work is urgent. The entire structure is under imminent threat from a nearby mountain stream, whose gradual erosion has begun eating into the mound’s outer edges. According to the AAFR, excavations began in November precisely to prevent the irreplaceable remains from being destroyed.

“We must document what we can before nature takes its toll,” AAFR officials stated during a special press viewing of the site. The ongoing fieldwork will continue through January 2026, allowing researchers enough time to meticulously analyze the grave’s construction, stratigraphy, and contents.

Better Preserved Than Its Predecessors

This newly uncovered mound is the third monumental grave identified at the same necropolis. Earlier excavations revealed similar burial structures, but none have matched the preservation level of the Grandvillard find. The integrity of the burial chamber, as well as the surrounding earthworks, allows researchers to reconstruct Iron Age funerary practices with unprecedented clarity.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Preliminary observations indicate that the buried individual was likely a figure of high social importance. While excavators have not yet made public a full catalogue of burial goods—those will only be confirmed after complete documentation—the site’s context strongly suggests parallels with earlier elite graves in the region. Previous discoveries in this necropolis included prestigious bronze offerings, a hallmark of upper-status burials across Iron Age Europe.

Clues to a Society Shaped by Climate and Landscape

One of the reasons archaeologists consider this find so significant is its potential to illuminate the social and environmental dynamics of the Intyamon Valley during the early Iron Age. This period, spanning roughly 800–450 BCE, was marked by climatic fluctuations known as the Iron Age Cold Period. Cooler temperatures and shifts in agricultural productivity often had direct effects on population patterns, settlement stability, and social organization.

Periods of environmental stress sometimes corresponded with simpler burial rites, whereas more prosperous decades produced more elaborate funerary monuments. Monumental mounds like the one in Grandvillard typically required substantial communal effort to construct, indicating not only the importance of the deceased but also a society capable of mobilizing resources collectively.

The Grandvillard mound—built with precision and designed to endure—suggests an era of considerable stability and social stratification. Its prominent location in the valley likely served both ceremonial and territorial functions, making the grave a marker of status visible to all who traversed the region.

An Exceptional Research Opportunity

Because the mound is so well preserved, it provides archaeologists with a chance to reconstruct burial rites in striking detail: the arrangement of the chamber, the placement of the body, the layering of the mound itself, and the selection of accompanying offerings. Each of these elements contributes to a broader understanding of Iron Age identity, belief systems, and social networks.

The AAFR’s work at Grandvillard also builds on a growing body of research showing that the western Alpine regions played a far more interconnected role in Iron Age Europe than previously assumed. Long-distance trade routes, cultural exchanges, and shared ritual customs all left their marks on funerary traditions.

Preserving the Past While the Clock Ticks

Despite the urgency posed by erosion, the excavation is proceeding with careful, methodical precision. Every stratigraphic layer is photographed, mapped, and sampled. The goal, the AAFR emphasizes, is not simply to remove artifacts but to capture the story of the monument before natural forces erase it.

Once the excavation and analyses are complete, researchers hope the findings will help clarify the social hierarchy of the Intyamon Valley and offer new insights into how ancient communities adapted to shifting climates.

For now, the monumental mound of Grandvillard stands as one of Switzerland’s most remarkable Iron Age discoveries—a testament to a society whose legacy, sealed beneath ten meters of earth for 26 centuries, is finally being brought back into the light.

Archäologie des Kantons Freiburg

Cover Image Credit: Excavations in Grandvillard. State of Fribourg