Archaeologists in Armenia have discovered a 2,500-year-old mysterious idol carved from volcanic tuff inside the ancient Urartian fortress of Argishtikhinili, a stronghold of the Kingdom of Urartu in the South Caucasus. The discovery, made during the second season of Armenian–Polish excavations, sheds new light on the spiritual and domestic life of the region’s inhabitants toward the end of the 7th and throughout the 6th century BCE. Alongside the idol, researchers also uncovered an extensive urn-field cemetery, believed to be the largest and best-preserved cremation site ever found in Armenia.

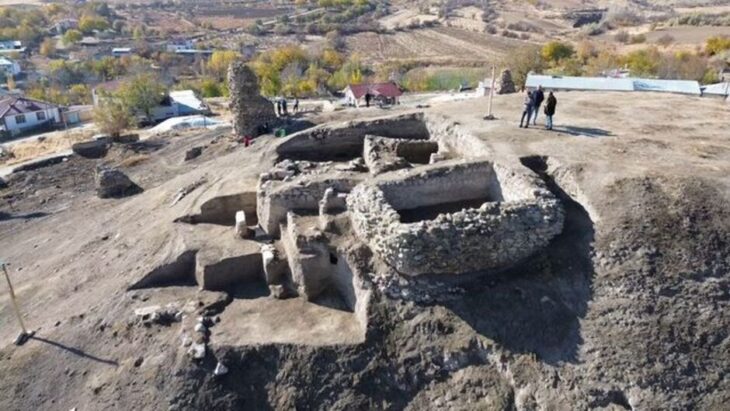

The excavations took place on Surb Davti Blur (St. David’s Hill), one of the two mounds that compose the fortified settlement. The work is led by Dr. Mateusz Iskra from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw (PCMA UW), and Dr. Hasmik Simonyan from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the National Academy of Sciences of Armenia, in collaboration with the Service for the Protection of Historical Environment and Cultural Museum-Reservations of the Republic of Armenia.

According to Dr. Iskra, the team focused on exploring a group of large, terraced houses dating to the late 7th–6th centuries BCE, an era corresponding to the twilight of the Urartian state. “Their preservation turned out to be astonishingly good,” he said. “In many places, mud-brick and stone-paved floors have survived almost intact, allowing us to see the organization of these ancient homes in great detail.”

Within one of the residential complexes, the archaeologists discovered a storage room containing large pithoi—ceramic storage vessels still embedded in the floor, exactly where they had stood more than two millennia ago. Yet, the most captivating find lay in the adjacent room: a volcanic tuff stone sculpted into a human face, resting beside a rectangular stone box. Measuring about half a meter in height, the figure displays prominent eyebrows, narrow lips, a long nose, and closely set eyes.

This idol-like figurine, preserved in its original position, likely served a ritual or protective function within the household. Comparable figures from other Armenian sites are thought to be linked to ancestor veneration or fertility cults, hinting that the people of Argishtikhinili maintained deep spiritual traditions rooted in both domestic and community life. Future chemical analysis of the stone chest’s contents may reveal organic residues—perhaps offerings or ritual materials—that could further clarify the idol’s role.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

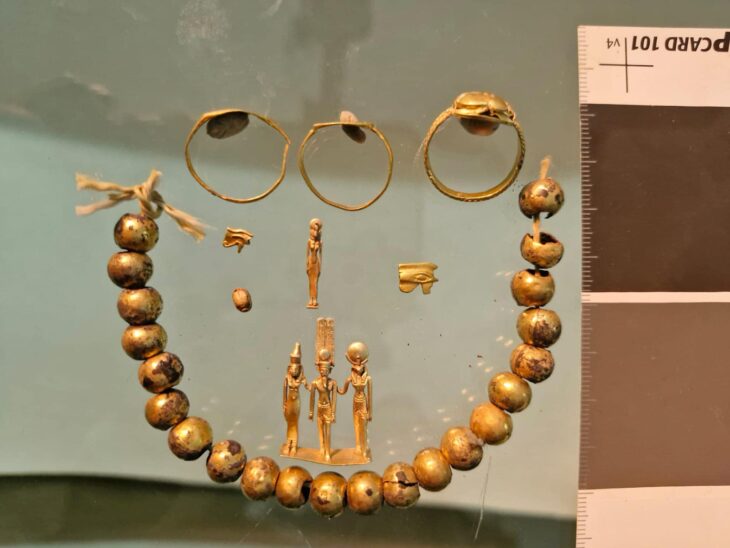

Parallel to these domestic excavations, Dr. Hasmik Simonyan and her team unearthed a vast urn-field cemetery on the outskirts of the settlement. The burial ground, containing dozens of cremation burials, revealed ceramic urns carefully filled with the ashes of the deceased, often accompanied by small grave goods such as ornaments or vessels. “This site represents a turning point in Armenian archaeology,” Simonyan explained. “It is very likely the largest and best-preserved cremation cemetery ever discovered in the country, offering an unprecedented glimpse into the funerary customs of communities under Urartian influence.”

The remarkable state of preservation of these urns provides researchers with valuable data on funerary practices, beliefs about the afterlife, and social hierarchy. Some urns belonged to adults, others to children, indicating a fully developed and codified burial system. This discovery opens new research avenues on how regional identities persisted and evolved after the decline of the Urartian central power.

Argishtikhinili and the Legacy of Urartu

Founded by King Argishti I of Urartu (785–760 BCE), Argishtikhinili stood as a strategic fortress and administrative center in the Ararat Plain. The Urartian kingdom—flourishing between the 9th and 6th centuries BCE—was one of the most advanced states of the Iron Age Near East. Its engineers built monumental fortresses, irrigation systems, and temples dedicated to deities such as Haldi, the chief god of war and sovereignty. Urartian cuneiform inscriptions carved in stone still echo across Armenia, eastern Türkiye, and northwestern Iran.

Argishtikhinili’s unique position at the crossroads of Anatolia and the Caucasus made it a vibrant node of trade and cultural exchange. The site’s architecture reflects both military precision and urban sophistication, with carefully planned terraces and large public buildings. Its eventual decline coincided with the collapse of the Urartian state around the early 6th century BCE, likely due to internal crises and the advance of the Medes.

Today, the ongoing Polish–Armenian project seeks to understand how the inhabitants of Argishtikhinili navigated that period of transition—how they reorganized daily life, sustained traditions, and adapted to new political realities after the fall of their kingdom.

“The biography of these households,” says Dr. Iskra, “tells us about resilience in times of state collapse. Argishtikhinili becomes a microcosm for studying how people live through the end of an empire.”

The next excavation phase, supported by a grant from the National Science Centre of Poland, will begin in spring 2026. The new research project—titled “Household Biographies during the Decline of State Structures”—will explore the city’s social and economic transformations during the Late and Post-Urartian periods, combining archaeological data with advanced scientific analyses.

A Bridge Between Nations and Eras

Beyond its historical revelations, the Argishtikhinili project symbolizes the growing collaboration between Armenian and Polish scholars in the field of Caucasian and Near Eastern archaeology. By combining expertise and technology, the joint team continues to reconstruct not only a forgotten chapter of Urartian civilization but also the timeless story of human adaptation, spirituality, and endurance.

In the shadow of Mount Ararat, the city once built by a king of Urartu is slowly rising again—stone by stone, idol by idol, urn by urn.

Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw (PCMA UW)

Cover Image Credit: Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw (PCMA UW)P. Okrajek