Throughout the history of Anatolia: a woman appears as a goddess with creative and productive powers, as a ruling monarch, as a patriotic citizen, patron of the arts, teacher, writer, and artist, and at all times as a mother guiding her family.

Anatolian women have always been well respected as a cult and figüre carrying big responsibilities on the strong shoulders.

When men settled down and began to work at farming for a living, there arose a natural division of work between man and woman. Woman, who was bestowed by nature with the duty of breeding, undertook the responsibility of household works. Among these household works there can be listed such primitive industrial handicrafts as making pottery, weaving carpets and making decoratiye lace-work in addition to the work on the farms. Man on the other hand was busy outside home with fighting and hunting that needed power and courage.

While new research reveals serious misconceptions about this division of labor, at least for a long time it was thought to be so.

Prehistory and Neolithic Age (9000-2000 BC)

In the daily life of most hunter-gatherers, women took part in hunting, feeding babies, sharing food, and maybe even making a wild salad in such plenty of greenery or playing games for fun.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

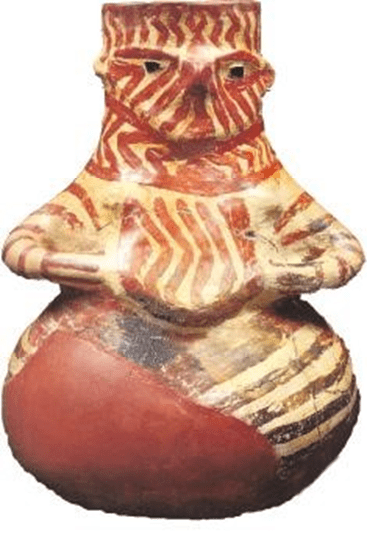

The hunting and gathering communities of the Upper Palaeolithic Age become aware of the sexual differentiation and fecundity of women for the first time and therefore associated women with the concept of fertility.

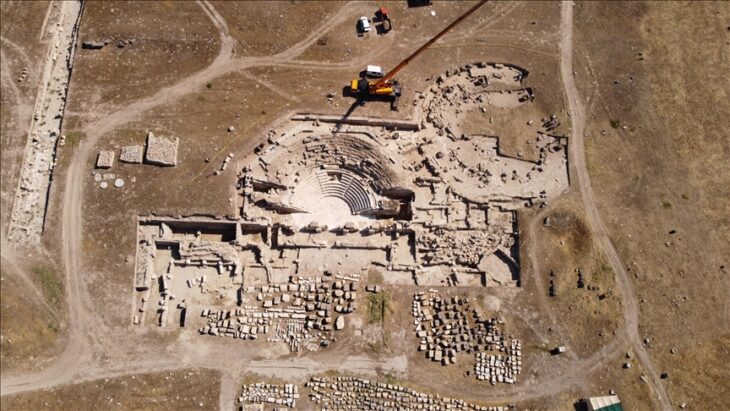

During the Neolithic Age, when human beings began cultivating the land and establishing permanent settlements, objects unearthed at such ancient settlements as Çayönü and Nevali Çori in southeastern Anatolia show that these people harbored religious beliefs centered around a fertility cult in which the woman was the predominant element.

Finds at the Neolithic settlement of Çatalhöyük, the largest in Anatolia, demonstrate that at the end of the 7th millennia B.C. belief in the supernatural made way for religious faith in the true sense. It was the Neolithic man who first drew a connection between the idea of creation and sexual relations and birth, manifesting this concept in a divine family consisting of god, goddess, and child.

The female goddess was the dominant element in the equation, with the power of birth, life, and death, and was seen as the protector of all creatures. The role of the woman in both religious beliefs and the family was equally preeminent a thousand years later, as proved by finds at Hacilar.

During the Bronze Age, women remained symbols of fertility, even if men had politically seized power. The sun goddess dominated the entire pantheon during the period when she was most dominant over society. The Sun goddess became a major impact on society.

By the end of this age, traders from the north (Upper) Mesopotamia, especially northern Syria, would be bringing perfume, textile, and tin to Anatolia and were able to get married to Anatolian women were very much respected as also seen on the marriage contracts of tablets found during the excavations at Kültepe in Kayseri served as a Karum of Anatolian traders exchanging goods Assyrian Trade Colones.

After this date, the written part of Anatolian history began BC.2000.

The Hittite Women (1700-1200 BC.)

Just before the establishment of Hiıtiıe civilization, ıhere was a matriarchy among the Anaıolian natives, women possessed individual seals and had the right own personal possessions.

In the Hittite State, the person of highest authority after the king is the king’s mother and she is called ‘Tavannana’ (The highest mother). Only the royal queens could attain the rank and: status of ‘Tavannana’. Thus the person who has this status’ comes next after the king in protocol during all the official! ceremonies and religious festivals. In some public festivities, only the queen represents the state.

Hittite legislation attached great importance to equality between men and women as we learn from written documents concerning property, marriage, and criminal law which applied to the common folk as well as to the nobility.

Kings and queens of the Hittite Empire which ruled most of Anatolia enjoyed equal powers and also served as chief priests and priestesses in the religious hierarchy.

For Western and Central Anatolia, the arrival of the Thracian communities in Anatolia, the collapse of the Hittite Empire, brings with it many political and cultural changes.

Women in Anatolia in the Iron Age

While Kingdoms such as Phrygian and Lydia were established in the Iron Age, Ionian City-states were formed on the Aegean coasts. When we look at Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia, new political formations emerge with the Iron Age.

The scarcity of documents on social life in the Iron Age does not inform us enough about the women of this period. In archaeological works, women appear as a profile associated with housework and housework.

While the cult of Cybele continues its influence in the west of Anatolia, a more closed society structure begins to form in eastern Anatolia. For example, in the Urartian state, female captives were given to soldiers in exchange for success. It is known that he was in their palaces in their harems. Unfortunately, there is no inscription giving information about the social life or lives of people in Urartu.

Where the role of women in government is concerned, the Caria Kingdom in Anatolia stands out, ruled on several occasions by queens, such as Artemisia I and II, after the death of their husbands. Queen Appollonis, wife of Attalos I of Pergamum and Queen Sinope and Queen Amastris of the Black Sea region in the 3rd century B.C. were famous as patrons as well as rulers.

Source: 1- “THE STATUS OF TURKISH WOMEN IN ANATOLIA”, Associate Professor Gülden Ertuğrul

2- “DEMİR ÇAĞI’NDA ANADOLU’DA KADIN”, Associate Professor Erkan Konyar