High in Chile’s northern Andes, where icy winds sweep across the desert ridges of the Camarones River Basin, archaeologist Dr. Adrián Oyaneder of the University of Exeter has uncovered an extraordinary network of ancient stone hunting traps that could rewrite what we know about Andean life long before the rise of the Inkas.

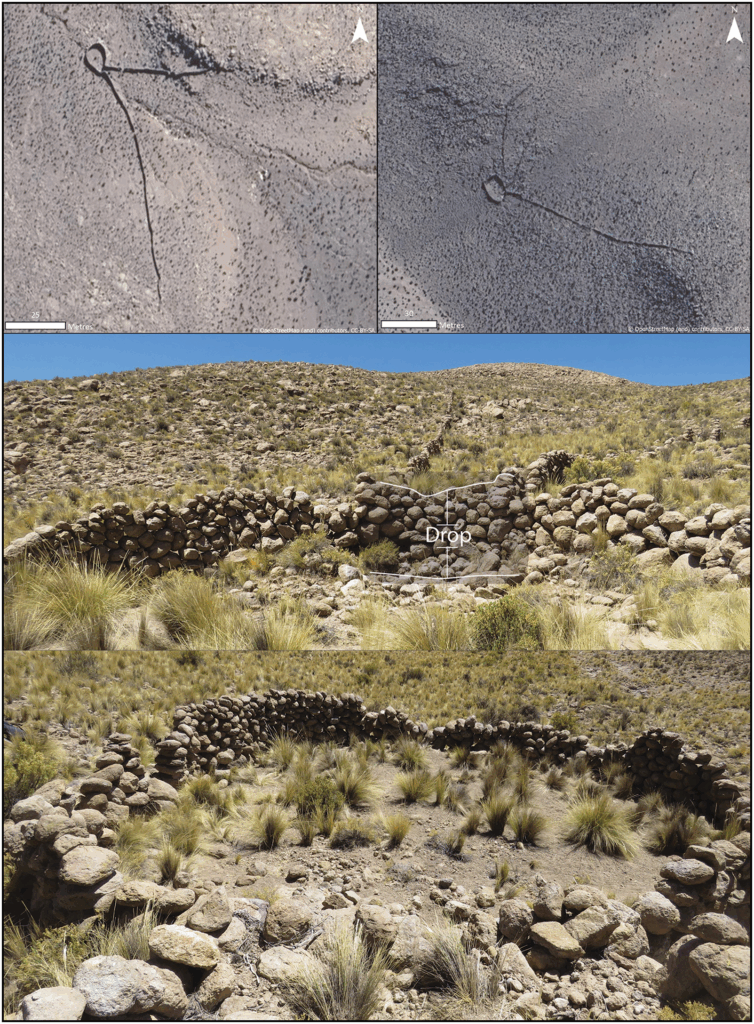

Through detailed analysis of satellite imagery covering 4,600 square kilometres, Oyaneder identified 76 massive, V-shaped hunting structures — some stretching over 150 metres — hidden among the barren slopes of the Atacama Desert’s highlands. These stone installations, known locally as chacus, once served as large-scale animal traps, ingeniously designed to funnel herds of vicuña, the wild ancestors of the alpaca, into enclosed pits or corrals.

“At first I thought I had found a single unique structure,” Oyaneder recalled. “But as I kept scanning, I realised they were everywhere — scattered across the mountains in numbers that had never been recorded in the Andes before.”

Ancient intelligence in stone

Each chacu consisted of two long stone “arms” — sometimes extending hundreds of metres — converging into a small, walled enclosure roughly 95 square metres in size and up to two metres deep. Hunters would drive herds of vicuñas between the walls, guiding them downhill into the trap’s narrowing funnel until they could be captured or killed.

The study, published in Antiquity and supported by Chile’s FONDECYT project and Becas Chile–ANID program, suggests that these traps may date back as early as 6000 B.C., long before the Inkas used similar systems. Their strategic placement — often on steep, rocky slopes at altitudes between 2,800 and 4,200 metres — shows a sophisticated understanding of both animal behaviour and mountain topography.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

According to Oyaneder, “The people who built these systems understood the movement of the animals, the terrain, and the seasons. The design wasn’t random — it was based on generations of observation.”

A landscape of movement

Beyond the hunting traps, Oyaneder mapped nearly 800 small settlement sites in the same region — from single-room shelters to clusters of circular stone huts. Many were located within a few kilometres of the chacus, forming what he describes as a “tethered mobility landscape”: a network of seasonal camps linked by the pursuit of wild herds and the shifting availability of water and vegetation.

GIS and satellite vegetation data confirmed that these sites followed the rhythm of the Andean seasons. During the short wet months (March–April), fresh pastures would emerge, drawing both animals and humans to higher altitudes. When the slopes dried out, groups moved lower, likely alternating between hunting, herding, and early forms of agriculture.

This pattern challenges long-held archaeological assumptions that hunting in northern Chile declined sharply after 2000 B.C., when domesticated crops and animals began to spread. Instead, Oyaneder’s data show that foraging and hunting endured for millennia, overlapping with herding and farming well into the colonial period.

Traces of forgotten peoples

The study also reopens questions about the identity of the “Uru” or “Uro”, foraging groups mentioned in Spanish colonial records from the 16th to 18th centuries. These communities — often described as “wandering fishers and hunters” — may have been direct descendants of the highland hunters who built the chacus.

Ethnohistorical sources even describe ritual hunts known as chacu or choquela, in which large groups cooperated to drive vicuñas into traps using ropes, music, and chanting. Similar ceremonies survived into modern times in parts of Bolivia and Peru, blending communal hunting with spiritual offerings to the mountains.

By combining remote sensing, spatial modelling, and cultural records, Oyaneder paints a vivid picture of a dynamic human landscape shaped by adaptation and resilience. Far from being a desolate wasteland, the Atacama’s uplands were once a finely tuned ecosystem where human survival depended on collective intelligence — and cooperation between hunters, herders, and nature itself.

“What we’re seeing,” Oyaneder notes, “isn’t a single culture frozen in time, but an evolving system — people tethered to the land, to water, and to the animals that sustained them. The Andes were alive with movement.”

A new chapter in Andean archaeology

The discovery also highlights the growing role of satellite archaeology in exploring remote, inaccessible landscapes. Using high-resolution imagery from Google Earth and Sentinel-2, Oyaneder’s team was able to identify ancient features invisible from the ground, revealing hundreds of previously undocumented sites.

His next goal is to date the structures directly and determine whether these chacus represent the earliest large-scale hunting systems in the Andes. If confirmed, they would predate Inka state-organized hunts by several thousand years — evidence that complex cooperation in Andean societies has roots deep in prehistory.

The findings are already reshaping our view of human adaptation in one of Earth’s harshest environments. In a landscape where life clings to thin air and salt-dusted stone, ancient hunters engineered survival through collective strategy — transforming the mountains themselves into instruments of the hunt.

Oyaneder, A. (2025). A tethered hunting and mobility landscape in the Andean highlands of the Western Valleys, northern Chile. Antiquity, 1–18. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10213

Cover Image Credit: Aerial photo of a double chacu above. University of Exeter