In late Bronze Age Europe, wealth was no longer buried with the dead. Instead, power was dismantled, recycled—and hidden in the ground. In 2019, deep in a quiet Danish forest, archaeologists uncovered the Hastrup Hoard: over 200 carefully broken bronze fragments buried for more than 2,500 years. But this was no ordinary treasure. Each piece had once been part of a coherent ensemble—ceremonial clothing, a horse harness, or wagon fittings—that once radiated authority and status.

And yet, here it lay, deliberately dismantled, fragmented, and hidden from the world. The Hastrup Hoard does not speak of wealth or display; it speaks of power undone. When bronze lost its value, authority did not vanish quietly—it was dismantled, recycled, and buried, a conscious act of neutralization. Beneath the forest floor, a society’s relationship with power itself was transformed, leaving behind a hoard that is as much about disappearance as it is about preservation.

What Happens to Power When Bronze Loses Its Value?

For centuries, bronze was power made visible. It shaped weapons, adorned elites, and traveled vast distances as a symbol of authority and connection. But around 800 BCE, something changed across Europe. Bronze began to lose its economic centrality. Iron emerged. Trade routes fractured. Old certainties dissolved.

The Hastrup Hoard, discovered beneath a quiet Danish forest, shows what happened next.

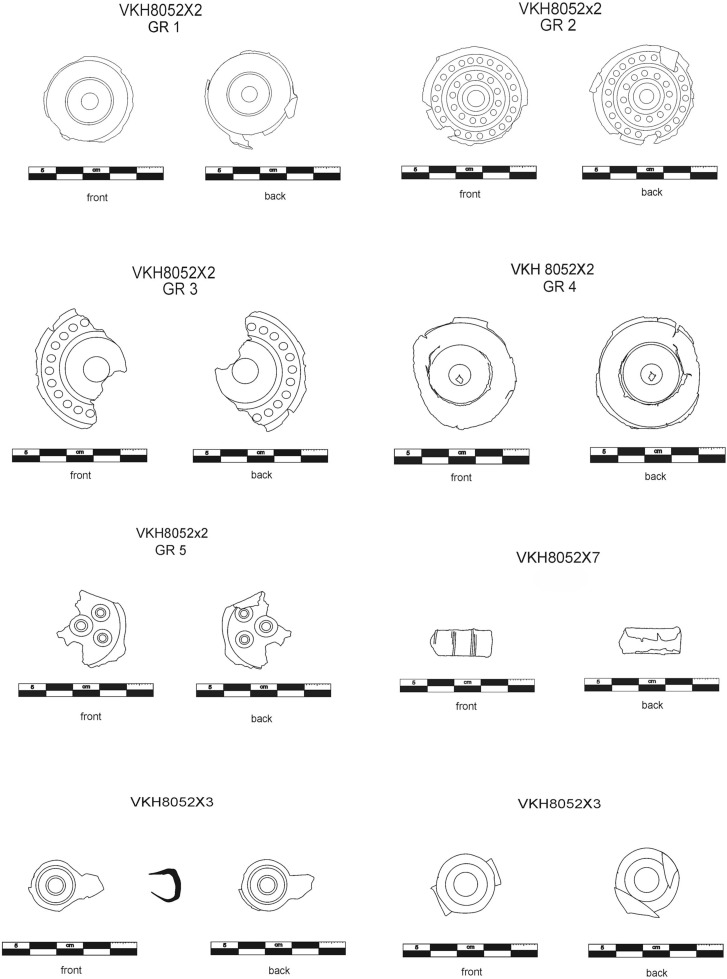

Unearthed in 2019, the hoard consists of more than 200 fragments of bronze, deliberately broken and carefully deposited. At first glance, it resembles many other Bronze Age hoards. But closer study reveals something far more revealing: this was not scrap metal, not hidden wealth awaiting recovery, and not a simple ritual offering.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

It was power, taken apart on purpose.

From Display to Disassembly

The objects buried at Hastrup once formed something coherent. Chemical and isotopic analyses show that many of the bronze plaques and sheets were made from the same metal batches, likely produced in the same workshop, possibly even at the same time.

These items were not random. Large decorated discs, smaller plaques with clamps, bronze tubes, and rings strongly suggest parts of a single ensemble—perhaps ceremonial clothing, a horse harness, or wagon equipment associated with elite display.

In Hallstatt Europe, far south of Denmark, such assemblages were symbols of authority, worn or displayed in rituals, processions, and burials. Yet in Denmark, these objects were never worn to the grave. They were dismantled, fragmented, and buried together.

Power was no longer something to be displayed eternally. It was something to be neutralized, transformed, or withdrawn.

Bronze After Bronze

The Hastrup Hoard also reveals that bronze itself was changing.

Scientific analysis shows that the metal had lived multiple lives before burial. Some objects were made from low-impurity copper, likely sourced from the southern Alps. Others contain fahlore-rich copper associated with regions such as Slovakia. In several cases, these metals were mixed together, indicating recycling and remelting of older objects.

This was not accidental. It reflects a world in which access to fresh copper was becoming unreliable, and older bronze objects were increasingly treated as material to be reworked, not symbols to be preserved.

Yet recycling alone does not explain Hastrup. If efficiency were the goal, the metal would have been reused—not buried.

Instead, bronze here seems to have crossed a threshold: from economic resource to symbolic residue.

When Wealth Leaves the Grave

The burial customs of northern Europe help explain this shift.

By the late Nordic Bronze Age, cremation had largely replaced inhumation. Graves became poorer, often containing few or no objects. Material wealth did not disappear—it moved elsewhere.

It accumulated in hoards.

Unlike graves, hoards were not about individual memory. They were about collective action. The Hastrup Hoard shows signs of deliberate selection, coordinated production, and intentional fragmentation. This was not the loss of wealth—it was its controlled removal from society.

By burying an elite ensemble intact-but-broken, communities may have been marking the end of its social power. What once commanded respect no longer belonged among the living.

Foreign Forms, Local Meaning

Stylistically, many of the Hastrup objects resemble Hallstatt craftsmanship from Central Europe. But they also contain features unknown outside Denmark, such as distinctive clamp systems on the backs of plaques.

This suggests that the objects were not simply imported and discarded. They were reinterpreted locally, woven into Nordic practices at a moment of transition.

The hoard does not speak of cultural imitation—it speaks of appropriation and closure. Whatever authority these objects once carried, it ended here.

The Final Act of Bronze Power

So what happens to power when bronze loses its value?

The Hastrup Hoard offers a clear answer: power does not vanish—it is dismantled.

It is melted, mixed, reshaped, then deliberately removed from circulation. It is buried not to be retrieved, but to be ended. In this sense, the hoard is not a treasure. It is a final act.

Hidden beneath the forest floor for more than 2,500 years, the Hastrup Hoard captures the precise moment when bronze stopped ruling Europe—and when power learned to disappear underground.

Felding, L., Berger, D., Lindblom, C., & Wrobel Nørgaard, H. (2025). The Hastrup hoard: Metallurgical and typological links between South Jutland and Hallstatt Europe in the 8th to 6th centuries BCE. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105533

Cover Image Credit: Hastrup Hoard, Denmark. Felding et al., 2025