For centuries, the massive stone statues of Easter Island—known as the moai—have stood as one of archaeology’s greatest enigmas. How could an isolated Polynesian society, without wheels, cranes, or large animals, have moved monuments weighing up to 80 tons across rugged terrain?

A groundbreaking study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science has finally revealed the answer: the moai didn’t just get dragged—they walked.

Rediscovering Ancient Genius

Between the 13th and 16th centuries, the inhabitants of Rapa Nui carved nearly a thousand moai from volcanic tuff. These towering figures, often mistaken for mere “heads,” actually have full bodies buried beneath the earth. Each statue represented revered ancestors and symbolized the power of the clan that erected it.

Yet the question of their movement remained unsolved for decades. Early European explorers speculated about lost civilizations or supernatural powers. Later researchers suggested sledges, rolling logs, or wooden tracks—but none fit the evidence. The island’s sparse vegetation couldn’t support large-scale timber transport, and the bases of the statues showed wear patterns inconsistent with dragging.

It took a modern blend of physics, 3D modeling, and experimental archaeology to uncover the truth.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

When Physics Met Archaeology

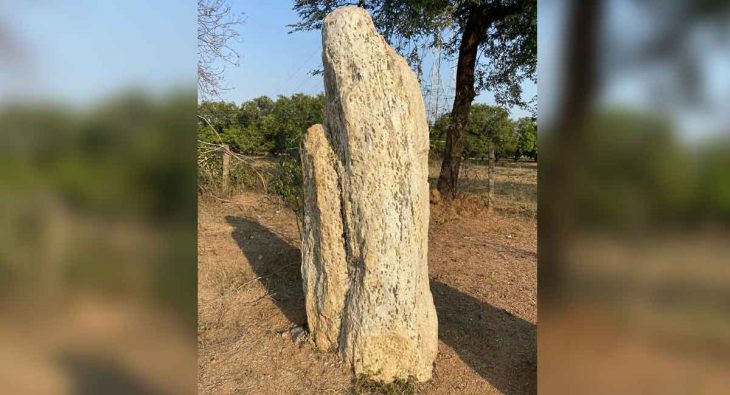

A team led by archaeologist Carl Lipo of Binghamton University and Terry Hunt of the University of Arizona analyzed high-resolution 3D scans of the statues. They discovered two key design traits: a D-shaped base and a slight forward tilt. These features weren’t accidental. They positioned the center of gravity in such a way that the statue could rock gently forward when pulled from the sides.

Lipo’s team then built a full-scale replica weighing 4.35 tons. With only 18 volunteers and three ropes, they managed to move it 100 meters in just 40 minutes. As the statue swayed side to side, it advanced slowly—just like a refrigerator being walked across a floor.

“The moment it starts moving, it almost comes alive,” said Lipo. “People pull from both sides, and the statue steps forward on its own. The larger it is, the more stable it becomes. Physics does the rest.”

The “Walking” Technique Explained

The process was elegant and efficient. Ropes were tied around the statue’s head or shoulders. Two groups stood on either side, pulling alternately to create a rhythmic rocking motion. Each swing shifted the center of gravity, causing the moai to tilt and pivot slightly ahead. A small forward lean in the design helped the statue self-correct and avoid falling backward.

Step by step, the giant “walked” toward its destination—balanced by nothing more than rope tension, gravity, and coordination.

Roads Built for Motion

Archaeological excavations revealed that the island’s ancient roads, averaging 4.5 meters wide, had a concave shape. This subtle curvature stabilized the swaying statues, preventing them from tipping sideways. Far from being ordinary roads, they were carefully engineered pathways designed for the movement of these sacred monuments.

“Every time they moved a moai, they literally built the road beneath it,” said Lipo. “Transportation wasn’t separate from construction—it was part of the same process.”

The discovery reframes Rapa Nui’s infrastructure as a dynamic system of movement and ritual, not just static routes between settlements.

Myth and Memory

Legends among the Rapa Nui people have long spoken of statues that “walked” to the shore under the guidance of ancestral spirits. For years, these tales were dismissed as myth. Now, science suggests they may contain a core of truth.

The walking method not only explains the islanders’ oral traditions but also restores respect to their ingenuity. Rather than an isolated people who destroyed their own ecosystem, the Rapa Nui emerge as innovative engineers who maximized limited resources and mastered balance, rhythm, and gravity.

Correcting the Myths

The study challenges several long-standing misconceptions. The moai were not dragged by thousands of slaves, nor were they products of a collapsed civilization. The evidence suggests a highly organized and sustainable society, capable of monumental construction through cooperation and scientific understanding.

Even the belief that the moai are only heads turns out to be false—most statues have fully carved torsos, buried by time and sediment. Each detail now contributes to a larger story of resilience and innovation rather than mystery and loss.

Remaining Questions and Ongoing Debates

While the walking hypothesis is strongly supported, researchers admit that not every moai may have moved this way. Smaller or damaged statues might have required modified methods, and getting the statue started from a standstill remains the trickiest phase. Some moai found toppled along transport routes suggest that accidents occurred during upright movement ther than horizontal dragging.

Still, no competing theory fits the geometric, archaeological, and experimental evidence as neatly. Future studies aim to test how teams coordinated their rhythm and how different terrains affected efficiency. What’s certain is that the moai’s movement was not brute force—it was physics in motion.

The Cultural and Scientific Legacy

Beyond solving a mystery, the walking moai project redefines how we perceive prehistoric innovation. The Rapa Nui people achieved extraordinary feats with nothing but stone tools, fiber ropes, and an understanding of balance that rivals modern physics. Their success was not mystical—it was mechanical genius born from observation, experimentation, and tradition.

As Lipo notes, “This discovery reminds us that ancient societies were not primitive. They were scientists of their world, engineers of their environment, and storytellers of their own history.”

Today, the moai still stand as silent guardians of Rapa Nui’s past—but thanks to modern science, they’re no longer frozen in mystery. They’re walking once again, one step at a time, across the bridge between legend and knowledge.

Carl P. Lipo & Terry L. Hunt (2025). The walking moai hypothesis: Archaeological evidence, experimental validation, and response to critics. Journal of Archaeological Science, 183: 106383.

Cover Image Credit: Public Domain