For decades, the monumental stone sites of Neolithic Anatolia have been explained through a familiar archaeological narrative. Towering pillars, dramatic animal reliefs, and recurring phallic imagery—most famously at Göbeklitepe—have often been interpreted as evidence of early male dominance, fertility cults, or the emergence of hierarchical religious authority. In both academic literature and popular media, the phallus is routinely assumed to symbolize masculinity, power, and control.

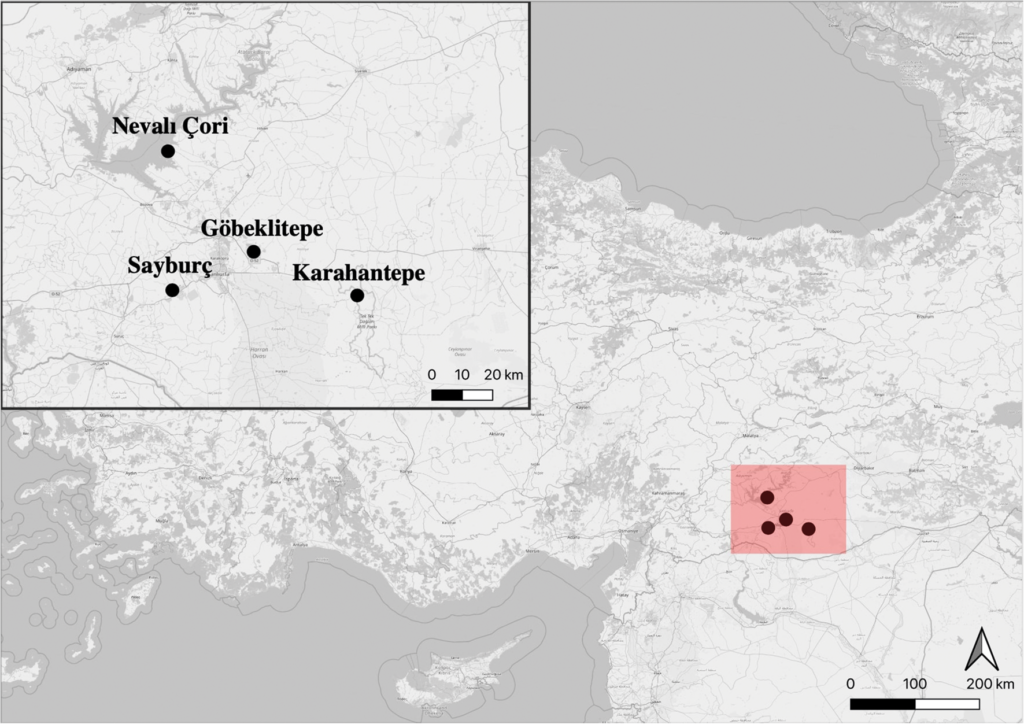

A recent academic study, however, challenges this deeply entrenched assumption. In A Queer Feminist Perspective on the Early Neolithic Urfa Region: The Ecstatic Agency of the Phallus, archaeologist Emre Deniz Yurttaş proposes a radically different interpretation of the phallic imagery found across the Taş Tepeler region, including Sayburç, Karahantepe, Nevalı Çori, and Göbeklitepe. Rather than reading these images as markers of male identity or patriarchal authority, the study argues that the phallus functioned as an active ritual agent, closely tied to ecstatic practices and altered states of consciousness.

Importantly, the term “queer” in this context does not refer to modern sexual identities. Yurttaş uses it as an analytical tool to describe non-normative uses of bodies, sexuality, and ritual—practices that disrupt contemporary assumptions about reproduction, gender roles, and the social boundaries of sex. From this perspective, sexuality is approached not as identity or symbolism, but as ritual action.

Why Sayburç Changes the Conversation

While Göbeklitepe remains the most well-known site, Yurttaş’s argument gains its sharpest focus at Sayburç. Here, a relief depicts a seated human figure grasping an erect phallus, flanked by animals. Unlike more abstract or fragmented imagery elsewhere, the Sayburç scene is explicit, corporeal, and unmistakably action-oriented.

This clarity matters. Previous interpretations of Neolithic phallic imagery have often avoided acknowledging sexuality, preferring symbolic readings that frame erections as metaphors for power or dominance over nature. The Sayburç relief, however, resists such abstraction. The figure is not simply marked by a phallus—it is actively engaging with it.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

According to Yurttaş, this makes it increasingly difficult to separate phallic imagery from sexual arousal itself, forcing archaeology to confront a dimension it has long marginalized.

From Symbol to Action

A central move in Yurttaş’s study is the shift away from asking whose body is represented toward asking what the body is doing. Across Taş Tepeler sites, phallic imagery consistently appears in an aroused state, yet rarely in reproductive or penetrative contexts. Instead, the images suggest solitary, repetitive, and performative acts.

From a queer feminist perspective, such acts—particularly autoerotic stimulation—have historically been excluded from serious archaeological interpretation. Because they do not lead to reproduction or social pairing, they are often dismissed as insignificant or reinterpreted as symbolic abstractions.

Yurttaş challenges this exclusion. He argues that the phallus should be understood not as a static symbol, but as an instrument capable of producing sensation, rhythm, and bodily intensity—key elements in the induction of altered states.

Ecstasy as Ritual Technique

Anthropological and ethnographic research provides a broader framework for this interpretation. Many non-industrial societies employ ecstatic techniques—such as dance, drumming, intoxication, and sexual stimulation—to access trance states that enable communication with non-human entities or spiritual realms.

Within this context, sexual arousal is not peripheral or taboo; it is technological, a means of transforming perception and experience. Yurttaş situates Taş Tepeler within an animistic worldview, where humans, animals, and objects exist in relational continuity rather than strict ontological separation.

Animal reliefs across the region—often dynamic, hybrid, or exaggerated—support this reading. Sexual ecstasy, the study suggests, may have been one of several embodied techniques used to cross perceptual thresholds during communal rituals.

Stones That Act

Another key element of the study concerns the role of stone itself. Rather than serving merely as a representational medium, carved reliefs may have been understood as active participants in ritual life.

Ethnographic parallels show that objects can be perceived as animated, capable of storing and releasing spiritual force. From this perspective, phallic imagery carved into stone pillars and walls may have extended access to ecstatic states beyond the limits of the human body.

This interpretation destabilizes long-standing assumptions about ritual participation. If ecstatic agency could reside in stone, then ritual power was not restricted to specific bodies, genders , or identities.

Rethinking Power in Neolithic Anatolia

Crucially, the archaeological record of the Taş Tepeler region does not support strong social hierarchies. There is little evidence for elite burials, wealth accumulation, or rigid social stratification. Instead, these communities appear to have been broadly egalitarian, organized around shared ritual practices rather than centralized authority.

Within such a social structure, phallic imagery cannot be easily read as an emblem of dominance. Yurttaş’s study instead suggests that ecstasy, not power, may have been the central organizing principle of ritual life in Neolithic Anatolia.

Why This Research Matters

By applying a queer feminist lens, Yurttaş’s work does not project modern identities onto the past. Rather, it exposes how modern assumptions have constrained archaeological interpretation. The study invites a reconsideration of the Neolithic as a period not only of technological and architectural innovation, but also of experimentation with bodies, sensation, and transcendence.

The Taş Tepeler sites remind us that the Stone Age was not simply about survival or control. It was also about ecstasy—and archaeology is only just beginning to take that seriously.

Taş Tepeler, it seems, was not just the birthplace of monumental architecture. It may also have been a place where bodies, spirits, and stones came together in ways that still unsettle modern expectations.

Yurttaş E. D. “A Queer Feminist Perspective on the Early Neolithic Urfa Region: The Ecstatic Agency of the Phallus.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 2025;35(3):489-503. doi:10.1017/S0959774325000083

Cover Image Credit: The Sayburç Relief. (Özdoğan Reference Özdoğan2022, fig. 4; photograph: Bekir Köşker.) Credit: Yurttaş E. D. (2025), Cambridge Archaeological Journal