Archaeologists have discovered six new Aramaic inscriptions at Zernaki Tepe, a 3,000-year-old ancient city in eastern Türkiye’s Van Province. The findings — including several deliberately erased inscriptions — shed new light on the Parthian-era presence in Eastern Anatolia and reveal traces of political conflict between ancient powers that once dominated the region.

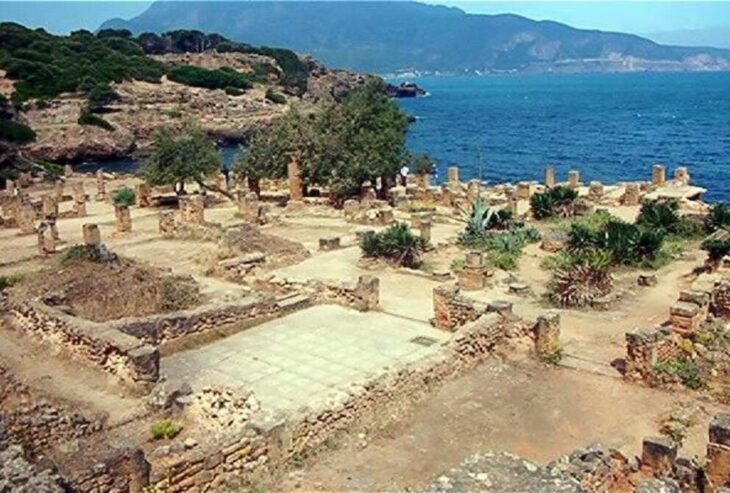

Located in Erciş district’s Yukarı Işıklı neighborhood, Zernaki Tepe spans an impressive 270 hectares, making it one of the largest known ancient urban centers in Eastern Anatolia.

Excavations are being carried out under the supervision of the Van Museum Directorate, with academic consultancy from Professor Rafet Çavuşoğlu, dean of the Faculty of Letters and head of the Archaeology Department at Van Yüzüncü Yıl University. The project is supported by the Van Governor’s Office and the Erciş District Governorate.

Parthian Influence and Erased Inscriptions

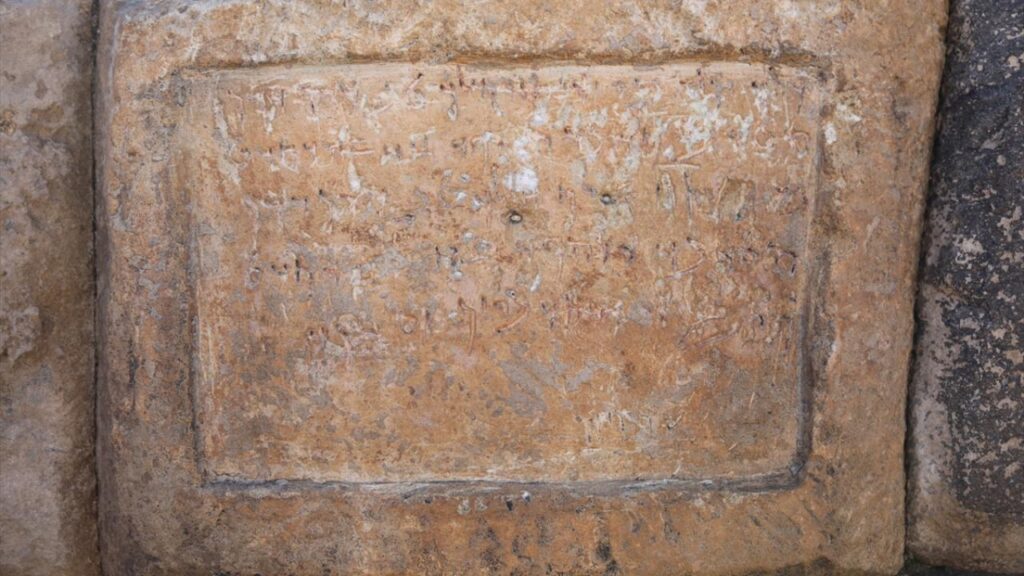

The newly discovered inscriptions, four of which were carved into the city’s defensive walls, are written in Aramaic — the administrative and cultural language of the Achaemenid and Parthian Empires.

Their discovery points to a Parthian-era settlement that may have served as a key frontier post between the Iranian and Anatolian worlds.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Professor Çavuşoğlu explained that three inscriptions had been deliberately erased, suggesting cultural or political upheaval:

“Some of the inscriptions were intentionally scraped off. This likely indicates inter-civilizational conflict or an effort by a later ruling power to erase the traces of the previous one.”

Experts believe that these markings could date to a transitional phase following Parthian rule, when emerging local powers and Roman provincial authorities sought to replace earlier symbols and administrative languages — a process often observed in frontier regions of ancient Anatolia.

A City Between Empires

Archaeological and historical evidence suggest that Zernaki Tepe thrived after the collapse of the Urartian Kingdom (9th–6th century BCE), when the Medes and later the Achaemenid Persians absorbed the region.

By the Hellenistic age, under the Seleucid Empire, the city adopted a grid-planned layout, resembling classical Hippodamian urban design.

When the Parthians extended their control westward in the 2nd century BCE, they inherited these urban foundations, transforming Zernaki into a fortified frontier settlement that mirrored both Iranian and Anatolian traditions.

Engineering and Infrastructure

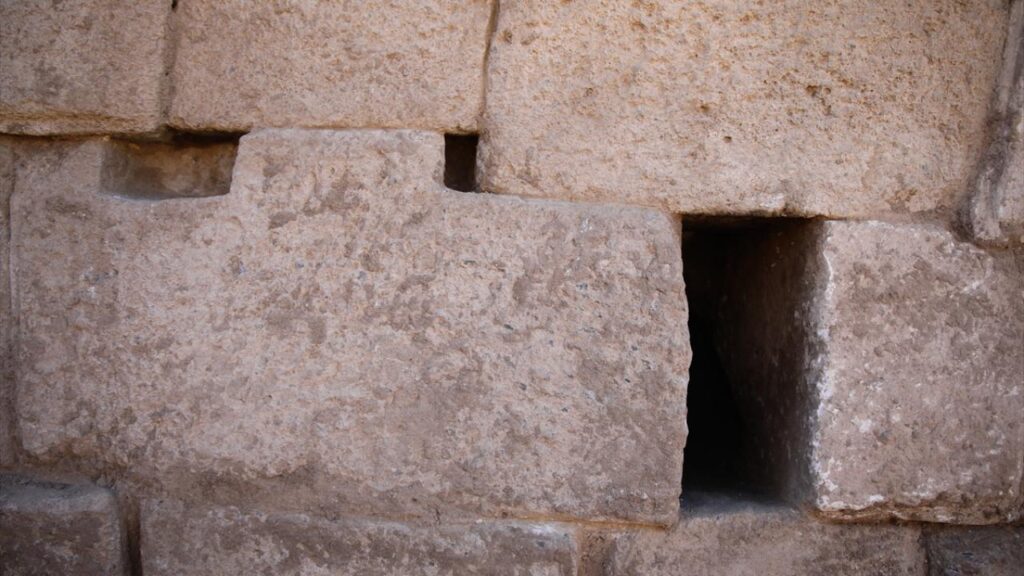

Excavations have also uncovered oval-shaped bastions, drainage channels, and fortification walls nearly 4.25 meters thick and three meters high, built from a combination of limestone and basalt.

The city’s drainage system, designed to discharge accumulated water from within the walls, demonstrates advanced urban planning and long-term occupation.

“This system shows a deliberate understanding of hydraulic engineering,” Çavuşoğlu said. “It’s clear that this was not a short-lived military base but a planned and sustainable urban settlement.”

Erased Memory in Stone

Aramaic, once the lingua franca of the Near East, remained in use throughout the Parthian era as a language of administration and royal inscription.

The deliberate erasure of certain texts at Zernaki Tepe may reflect a later Roman-era reoccupation, when new rulers sought to impose their own cultural and religious identity.

Professor Çavuşoğlu noted that such actions were “a symbolic form of rewriting history — an act used by later powers to erase or neutralize the presence of their predecessors.”

Zernaki Tepe’s Rediscovery

District Governor Murat Karaloğlu highlighted the importance of the site:

“With these six new inscriptions, the total number of Aramaic texts found here has reached fourteen. We believe this area marks the monumental entrance to the ancient city, which could date back around 3,000 years.”

Each newly uncovered stone fragment offers another piece of the long-forgotten political puzzle of Eastern Anatolia.

As researchers continue to unearth Zernaki Tepe’s buried past, one thing becomes clear: every erased word in stone carries the echo of an empire that refused to be forgotten.

Cover Image Credit: AA