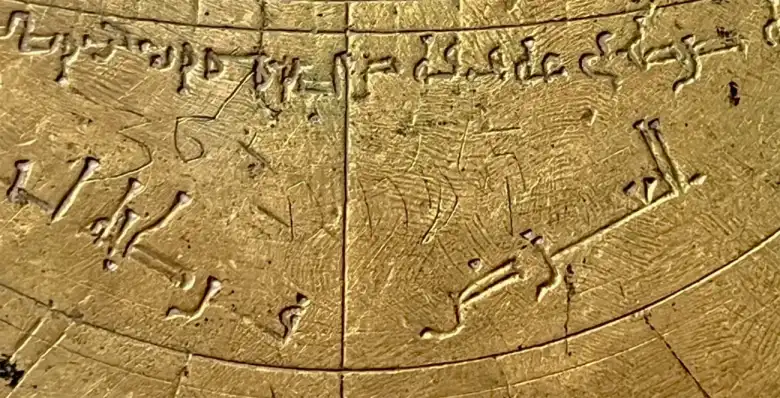

An eleventh-century rare astrolabe bearing Arabic and Hebrew inscriptions was recently discovered in a museum in Verona, Italy. It dates from the 1100s, making it one of the oldest astrolabes ever discovered.

The discovery of ancient astronomical tool bearing Arabic and Hebrew inscriptions has unveiled a rich tapestry of scientific exchange among Arabs, Jews, and Christians during medieval times.

Its history tells a fascinating story of centuries-long adaptation, translation, and revision by Muslim, Jewish, and Christian scholars in Spain, North Africa, and Italy.

Astrolabes are early scientific calculators that could measure time, distances, and the position of stars, and even make horoscopes predicting the future. They are pocket-sized maps of the universe that enable users to plot the position of the stars.

Dr Federica Gigante, from Cambridge’s History Faculty and Christ’s College, made the discoveries in a museum in Verona, Italy, and just published her study in the journal Nuncius.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“The museum didn’t know what it was and thought it might actually be fake. It’s now the single most important object in their collection,” said Dr. Federica Gigante.

Dr Gigante first came across a newly-uploaded image of the astrolabe by chance on the website of the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo. The 1,000-year-old astrolabe was identified by complete chance.

“When I visited the museum and studied the astrolabe up close, I noticed that not only was it covered in beautifully engraved Arabic inscriptions but that I could see faint inscriptions in Hebrew. I could only make them out in the raking light entering from a window. I thought I might be dreaming, but I kept seeing more and more. It was very exciting.”

“This isn’t just an incredibly rare object. It’s a powerful record of scientific exchange between Arabs, Jews, and Christians over hundreds of years,” said Dr. Gigante.

“The Verona astrolabe underwent many modifications, additions, and adaptations as it changed hands. At least three separate users felt the need to add translations and corrections to this object, two using Hebrew and one using a Western language.”

She deduced that it was initially created in 1100s Muslim-ruled Spain by looking at its unique features and inscriptions. The latitudes of the inscriptions correspond to cities in Spain, such as Toledo and Cordoba.

Dr. Gigante believes the astrolabe was possibly made in Toledo, which back then was an important center where Muslims, Jews, and Christians lived, studied, and worked side-by-side.

Subsequent owners of the astrolabe added Hebrew inscriptions, rendering Hebrew names for zodiac signs and other terms. This means that the astrolabe probably made its way to Italy at some point, where the local Jews had stopped speaking Arabic. However, the Hebrew additions contain an error about latitude, indicating that they were not written by an astrolabe expert.

In the Roman numerals that we still use today, some numbers were also very faintly inscribed. According to Dr. Gigante, these were even later additions made by Verona residents who spoke Latin or Italian. Interestingly, some of their “corrections” were actually incorrect, demonstrating that the original Arabic values were more accurate.

This finding underscores the significance of cross-cultural cooperation in advancing science and deepens our understanding of past scientific practices.

Cover Photo: The astrolabe of Verona. Photo: Federica Gigante / University of Cambridge