A groundbreaking reinterpretation of Poverty Point—one of North America’s most iconic archaeological sites—is challenging long-held assumptions about the people who built its massive earthen monuments 3,500 years ago. New research from Washington University in St. Louis proposes that this vast complex in northeast Louisiana was not the work of a rigid hierarchy or a powerful ruling class, but rather a collaborative gathering place for egalitarian hunter-gatherer groups united by shared ritual obligations.

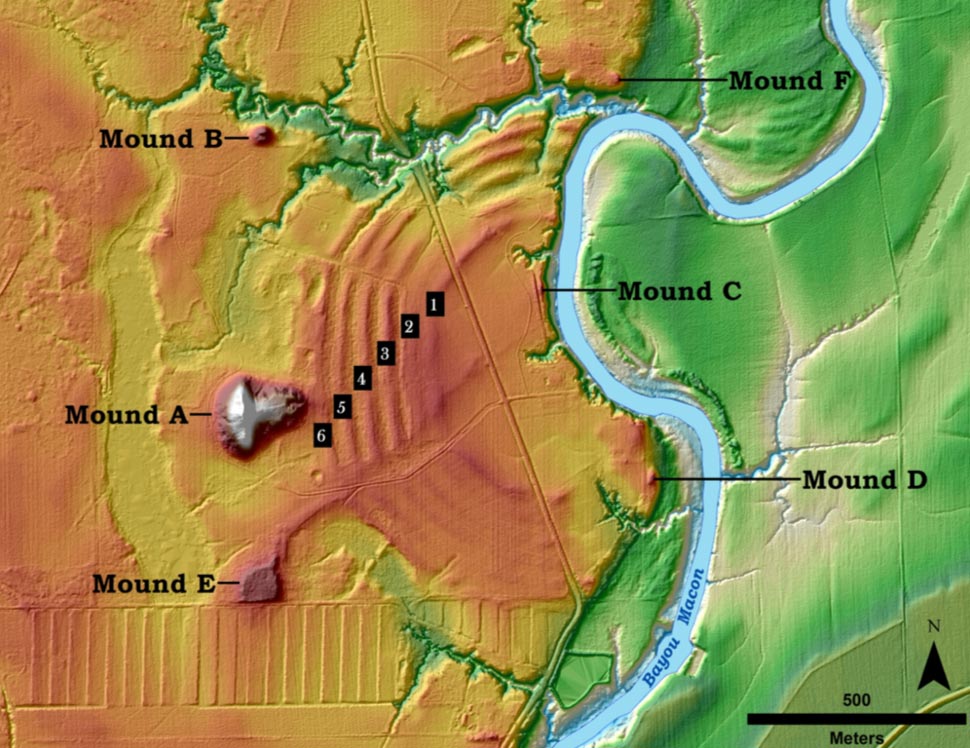

Located along the Mississippi River, Poverty Point is famed for its monumental earthworks, including concentric ridges and towering mounds that still dominate the landscape today. The scale of construction has always astonished researchers. Without horses, wheels, or agricultural infrastructure, ancient builders transported and shaped an estimated 140,000 dump-truck loads of soil—an extraordinary achievement that has puzzled archaeologists for decades.

Challenging the Old Model of Social Hierarchy

For many years, scholars believed that only a stratified society—a chiefdom with leaders who could command labor—was capable of organizing such monumental work. This assumption was largely based on comparisons with the later Cahokia Mounds in present-day Illinois, where a clear political hierarchy existed more than a millennium after Poverty Point.

However, new studies led by anthropologist T.R. Kidder dispute this interpretation. Published in Southeastern Archaeology and co-authored with graduate researcher Olivia Baumgartel and archaeologist Seth Grooms, the research argues that Poverty Point was neither a permanent village nor a politically centralized hub. Instead, evidence points to a periodic gathering place where thousands of people came together to trade, build, celebrate, and participate in shared rituals.

According to Baumgartel, the emerging picture is one of a community defined not by social ranks but by collective purpose. “We believe these were egalitarian hunter-gatherers,” she notes. “There is no archaeological indication of chiefs directing their labor.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

A Crossroads of Long-Distance Connections

Artifacts found at the site reveal a remarkable network of interaction stretching across much of eastern North America. Thousands of clay cooking balls, quartz crystal from the Ozarks, soapstone from the Atlanta region, and copper ornaments originating near the Great Lakes all point to extensive trade and travel.

These materials show that Poverty Point was not isolated but deeply connected to distant communities. The diversity of artifacts supports the interpretation of the site as a ceremonial destination—a place visited by groups converging from far-flung regions for shared cultural experiences.

Spiritual Purpose at the Heart of Construction

One of the most significant clues supporting the new theory is what archaeologists haven’t found. Despite decades of excavation, there is no evidence of long-term habitation: no cemeteries, no substantial houses, and no continuous domestic activity. These absences strongly suggest that Poverty Point was not a permanently occupied settlement.

Kidder and his team propose that the massive earthworks served as spiritual offerings during a time of unpredictable environmental conditions. The ancient Southeast was prone to destructive floods and extreme weather. In response, communities may have built monumental structures, performed rituals, and deposited valuable objects in an effort to restore balance and maintain harmony with their world.

This perspective has been strengthened through conversations with Native American communities, including members of the Lumbee tribe, of which co-author Seth Grooms is a member. These discussions highlight the importance of understanding Indigenous worldviews, which often emphasize communal responsibility and cosmological balance rather than economic gain.

Rewriting the Regional Timeline

The Washington University team also examined two related sites—Claiborne and Cedarland—in western Mississippi. Although these locations have been damaged over time, archived artifacts allowed for new radiocarbon dating. The results revealed that Cedarland predates Poverty Point by roughly 500 years, giving it a distinct cultural history.

This discovery helps disentangle the timelines of neighboring sites and provides a clearer picture of how materials and ideas moved across the region. As Baumgartel notes, giving each site its own chronology allows researchers to reconstruct the broader networks that shaped early North American societies.

Modern Tools, Ancient Insights

To further refine their understanding, Kidder and Baumgartel re-excavated several pits originally dug in the 1970s. With updated dating techniques and advanced microscopy, they aim to uncover subtle traces overlooked in earlier fieldwork.

Their painstaking approach mirrors the dedication of the ancient builders themselves. Each fragment of soil, each microscopic clue, brings archaeologists closer to understanding the motivations of a community whose monumental creations continue to inspire awe.

As Kidder reflects, the collaborative spirit behind Poverty Point may be its most enduring legacy—a reminder that some of the world’s greatest achievements arise not from power, but from shared belief and collective effort.

Kidder, T. R., & Grooms, S. B. (2025). Performance, ritual, and revitalization at Poverty Point. Southeastern Archaeology, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0734578X.2025.2553970

Kidder, T. R., Baumgartel, O. C., & Bruseth, J. E. (2025). High-resolution dating of legacy collections from the Cedarland and Claiborne sites, southwest Mississippi. Southeastern Archaeology, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0734578X.2025.2552058

Cover Image Credit: Mound A at Poverty Point. Wikipedia