One of Northern Europe’s most enigmatic archaeological finds—the 2,400-year-old Hjortspring Boat—may finally be giving up its secrets. New scientific analyses, combined with historical data preserved at the National Museum of Denmark, point to a surprising conclusion: the iconic war canoe was likely built far from Danish shores, in pine-rich regions along the eastern Baltic Sea.

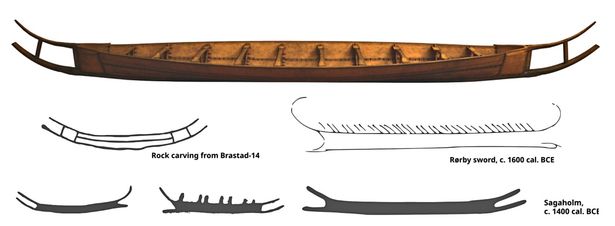

The study, published in PLOS One, offers the most comprehensive investigation to date of the oldest plank-built vessel in Northern Europe. Measuring nearly 20 meters long, the sleek, ultra-light boat once ferried up to 24 armed warriors, powered by maple paddles and crafted from lime-wood planks sewn together with bast cordage. Its elegant “horned” prows—curving extensions at both ends—echo shapes found in Bronze Age Scandinavian rock carvings, suggesting a deep continuity of maritime tradition.

But where the vessel came from has remained a puzzle for nearly 150 years.

A Bog Find That Rewrote Prehistory

The Hjortspring Boat was discovered in the late 1880s on the island of Als in southern Denmark, buried in the peat of Hjortspring bog. When archaeologists began methodical excavations decades later, they uncovered more than just a ship. Surrounding the vessel lay swords, spearheads, chainmail, and 50 Celtic-style shields—a full arsenal intentionally bent, broken, and deposited with the boat.

The arrangement strongly suggested a dramatic event: sometime in the 4th century BCE, a force of around 100 attackers—likely arriving in multiple ships—attempted a raid on the island. They were defeated, and the victors sank the captured enemy weapons and one of their boats into the bog as a ritual offering of triumph.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

But the attackers’ origin—Jutland? northern Germany? southern Sweden?—remained a matter of debate.

New Science Points East

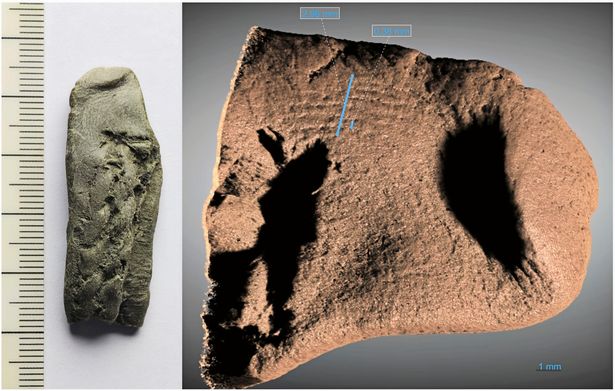

Until now. Researchers revisited neglected fragments from the original excavation—tiny samples of caulking tar and bast cordage that were never chemically treated. Using radiocarbon dating, high-resolution X-ray tomography, and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, they uncovered astonishing new details:

- The boat’s date is now confirmed.

A bast cord sample returned a direct radiocarbon date between 381 and 161 BCE, perfectly aligning with previous indirect estimates. This makes it a firmly Pre-Roman Iron Age vessel, active during a period of growing interregional conflict across Northern Europe.

2. The caulking was made with pine pitch and animal fat.

This is the discovery that changes everything.

During the Iron Age, pine trees were extremely rare in Denmark due to millennia of deforestation. Shipbuilders there typically used birch tar or mixtures of linseed oil and tallow. Pine pitch, however, was abundant in the Baltic regions east of Rügen, Scania, Bornholm, Gotland, and northern Poland, where vast conifer forests still thrived.

This strongly suggests the boat was constructed in the Baltic—not in Denmark.

- A fingerprint of an ancient boatbuilder

Perhaps the most human detail emerged from a fragment of caulking: a perfectly preserved partial fingerprint, likely left by a crew member during an onboard repair. Though not identifiable, the print gives a direct physical connection to someone who sailed the vessel more than two millennia ago.

Engineering from the Bronze Age, Warfare from the Iron Age

The National Museum of Denmark describes the vessel as a fast, maneuverable warship, weighing just over 530 kg—light enough for a crew to beach or portage. Its construction method, using lime-wood planks sewn with bast, preserves techniques with roots in the late Nordic Bronze Age, linking the boat to a long lineage of Scandinavian maritime craftsmanship.

Reanalysis of the cordage reveals a sophisticated rope-making tradition involving:

Two-ply S-spun bast strands

Expert balancing of twist and tension

Repair-ready strings likely kept untarred aboard

Experimental reconstructions show that these flexible cords could be subtly doubled, producing both 2-ply and 4-ply impressions in the caulking—a detail that puzzled archaeologists for decades.

A Long-Distance Attack Across the Open Sea

If the boat was truly built somewhere along the eastern Baltic, the implications are dramatic.

A raiding party would have needed to traverse hundreds of kilometers, navigating open sea, island chains, and treacherous straits before landing on Als. The journey suggests a highly organized, politically coordinated offensive rather than a local skirmish. The scale echoes patterns of large-scale Bronze Age conflicts—most famously the Tollense Valley battlefield in Germany—and hints that maritime coalitions remained influential even after the end of the Bronze Age’s long-distance metal trade networks.

Solving a 2,400-Year-Old Mystery

While the study does not pinpoint one exact location, all evidence now convergeson a single conclusion:

The Hjortspring Boat was almost certainly not Danish in origin.

It was a foreign warship—possibly from Bornholm, Gotland, Blekinge, or northern Poland—whose warriors undertook a bold, long-range maritime assault on the Danish archipelago.

Their defeat, and the ritual burial of their vessel, left behind one of Scandinavia’s most spectacular archaeological time capsules.

Today, the boat’s reconstructed form stands on display in Copenhagen, its lime-wood body and gently curving prows a silent reminder of an age when warriors crossed the Baltic in lightweight, hand-sewn vessels—and when a single fingerprint could survive 24 centuries to tell their story.

Fauvelle, M., Bengtsson, B., Pipping, O., Hollmann, M., Mortensen, M. N., Toft, P., Ganji, S., Green, A., Horn, C., Hall, S., Kaul, F., & Ling, J. (2025). New investigations of the Hjortspring boat: Dating and analysis of the cordage and caulking materials used in a pre-Roman Iron Age plank boat. PLOS ONE, 20(12), e0336965. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0336965

Cover Image Credit: National Museum of Denmark