Archaeologists in southeastern Türkiye have discovered a previously unknown Roman settlement dating to the 4th century AD — a site that may, based on its location and landscape features, lie within the broader territory once occupied by the lost city of Arsameia on the Euphrates.

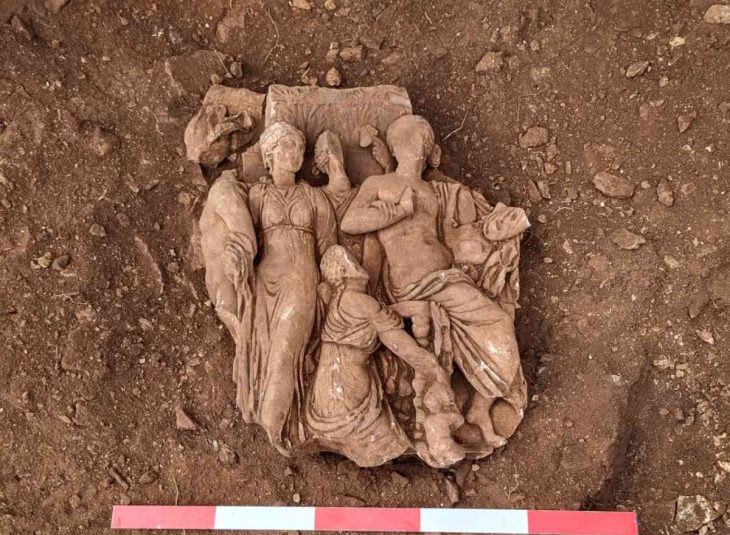

Situated in the mountainous terrain near Oymaklı village in Adıyaman’s Gerger district, the settlement extends across approximately 150 dönüms (37 acres). Excavations carried out under the supervision of the Adıyaman Museum Directorate have revealed architectural foundations, grape presses, cisterns, and grinding stones, indicating a productive rural community that thrived some 1,600 years ago during the late Roman period.

While no inscriptions or urban fortifications have yet been identified, the site’s proximity to Gerger Castle—historically associated with ancient Arsameia—supports the hypothesis that the newly found settlement may represent one of its outlying districts or agricultural extensions.

Note: Interpretations suggesting a possible connection with ancient Arsameia are the author’s own.

A 1,600-Year-Old Wine Production Center

Excavations have revealed multiple grape-press installations, water cisterns, grinding stones, and stone foundations spread across the site. Preliminary analysis dates the structures to the 4th century AD, corresponding to the Late Roman period.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

According to Mehmet Alkan, Director of the Adıyaman Museum, the layout and surviving architecture point to a large-scale wine production complex:

“We found several grape-press basins, cisterns, and grinding stones. The presence of multiple wine installations suggests industrial-scale production,” said Alkan.

“Although the walls were built with irregular stones, the foundations have survived remarkably well. This shows that we are standing in a significant ancient zone, likely active 1,600 years ago.”

The Adıyaman Museum has applied to the Şanlıurfa Regional Council for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage to register the area as a protected archaeological site.

Between Mountains and Memory

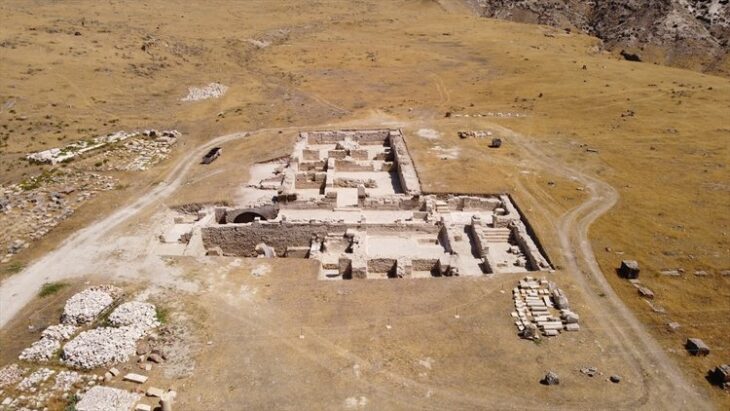

While the discovery clearly dates to the Roman era, its broader historical identity remains open to interpretation. The site’s proximity to Gerger Castle — a monumental stronghold perched above the Euphrates — has raised intriguing possibilities.

Gerger Castle itself has long been associated with Arsameia on the Euphrates, one of two ancient cities founded by King Arsames of Commagene in the Hellenistic period. Classical references, such as the Oxford Classical Dictionary, describe “Arsameia by the Euphrates (modern Gerger)” as the counterpart of Arsameia on the Nymphaios near Kahta, where monumental inscriptions of King Antiochus I Theos were found.

Although no direct inscriptions or numismatic evidence have yet tied the new Oymaklı site to Arsameia, its position — within several kilometers of the ancient fortress — fuels the hypothesis that it could represent a rural extension, lower quarter, or agricultural suburb of the lost city.

Archaeologists caution that such a connection remains hypothetical until detailed stratigraphic excavation and epigraphic analysis are undertaken. Still, the convergence of geographical, architectural, and cultural indicators keeps the idea alive.

A Forgotten Landscape of Production

If the assumption proves correct, the site could dramatically expand the known footprint of Arsameia on the Euphrates. Previous research has mostly focused on the Kahta-side Arsameia, while Gerger’s counterpart remains poorly documented archaeologically despite its frequent appearance in ancient sources and local oral history.

Large-scale wine production was common in the late Roman Near East, reflecting both commercial and ritual demand. In Commagene, where Hellenistic and Eastern traditions blended, wine held economic and symbolic significance. The grape-presses and cisterns found near Oymaklı may thus illustrate the agrarian backbone of an urban or military center — whether Arsameia itself or another Romanized settlement within its sphere.

The strategic setting also supports this interpretation. Gerger overlooks the Euphrates corridor, once controlling access between northern Mesopotamia and the Anatolian highlands. The Roman and Byzantine empires both fortified the region heavily, reusing older Commagene fortresses like Gerger (ancient Arsameia) and Kahta (Yeni Kale).

Waiting for Proof Beneath the Soil

The Adıyaman Museum team plans further documentation and limited sondages to clarify the site’s function and chronology. Specialists from regional universities are expected to conduct architectural mapping, petrographic studies, and residue analysis of the grape-press basins to confirm wine production.

Until then, the question lingers: was this complex part of Arsameia’s rural infrastructure — or an entirely new name in the Roman geography of Commagene?

For now, the discovery expands the archaeological map of southeastern Türkiye, offering a rare glimpse into rural industry and adaptation during the late Roman centuries. Whether or not Arsameia’s shadow still lingers over these hills, the soil of Gerger continues to rewrite the region’s ancient history — one stone and one press at a time.

Note: All interpretations suggesting a potential connection with ancient Arsameia are those of the author and should not be considered as confirmed archaeological conclusions.

Cover Image Credit: Orhan Pehlül/AA