In a remarkable study, Japanese archaeologists have digitally and physically resurrected fishing nets from the Jomon period, offering an unprecedented glimpse into prehistoric technology and cultural practices.

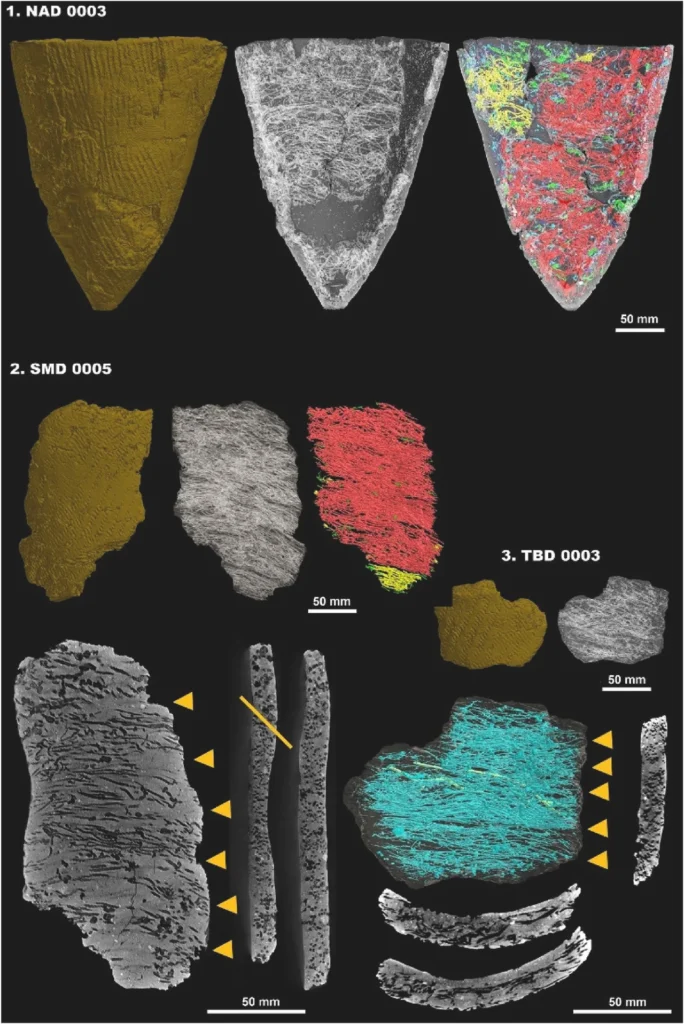

The research, led by Hiroki Obata and Yoon-ji Lee of Kumamoto University, combines cutting-edge X-ray computed tomography (CT) scans with silicone casting techniques to reconstruct nets that vanished millennia ago but left their traces hidden in pottery fragments.

A Window into the Jomon World

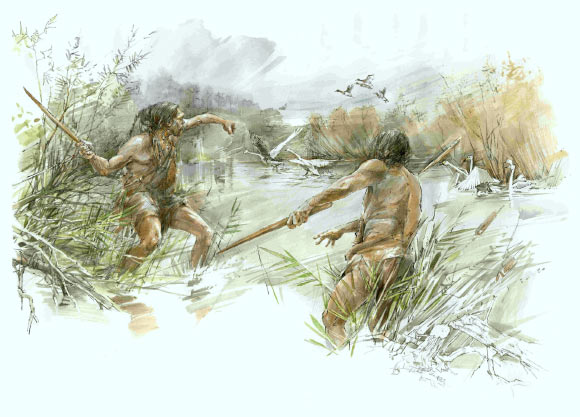

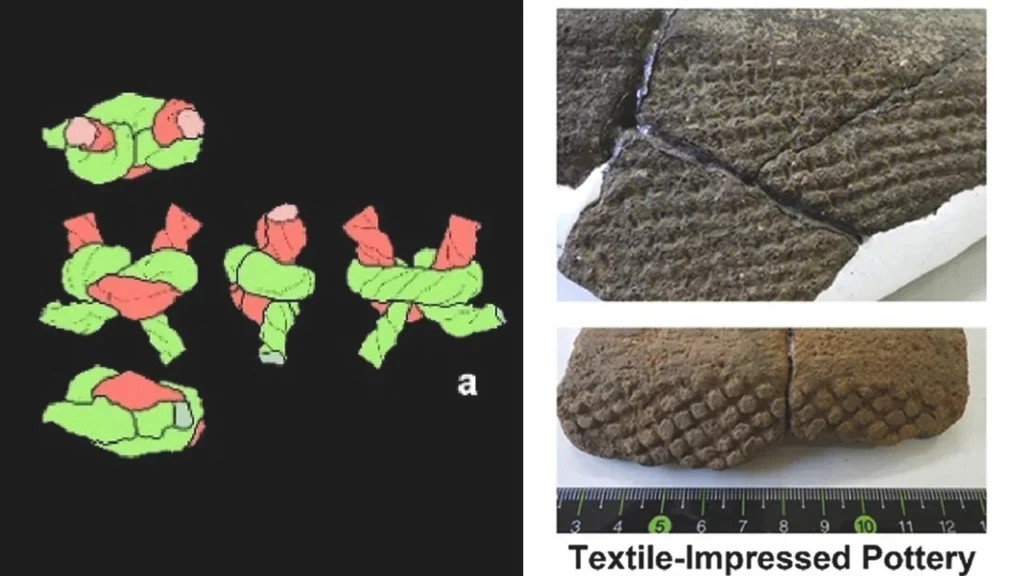

The Jomon period (14,000–900 BCE) was a transformative era in Japan, defined by hunter-gatherer societies who relied heavily on fishing. Archaeologists have long known about the era’s shell mounds, fish remains, and tools. Yet, one of the most essential items—fishing nets—remained elusive, as plant fibers rarely survive the test of time. Until now, researchers relied mainly on indirect evidence: net-shaped impressions on ceramics known as “textile-impressed pottery.”

The new study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, has confirmed that these impressions were indeed made by fishing nets, while also revealing surprising alternative uses. This is the first scientific reconstruction of prehistoric Japanese nets based on pottery evidence.

Rediscovering Nets Through Pottery

The team examined pottery from two distant regions: Hokkaido in the north and Kyushu in the south.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

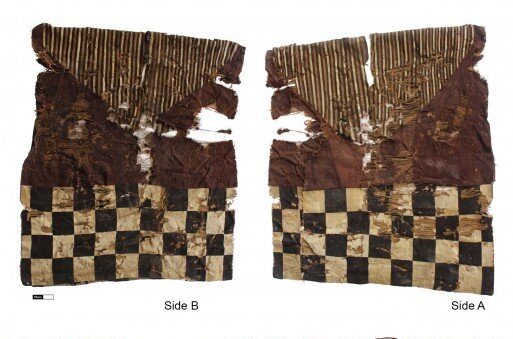

Hokkaido (Shizunai-Nakano style pottery, ca. 6000 years ago): CT scans revealed large-mesh nets tied with reef knots. These nets were not discarded after use but repurposed as reinforcement for pottery construction. Bundled and tensioned nets were integrated into clay coils, making them essential to pottery production.

Kyushu (Final Jomon and Early Yayoi pottery, ca. 3200–2800 years ago): Here, impressions revealed fine-mesh nets, often less than 6.5 millimeters. Unlike the robust northern nets, these were likely not for fishing but for alternative uses—such as containers, molds, or release agents in pottery-making. Many bore simple overhand knots or a technique known as “knotted wrapping,” more akin to fabric weaving than fishing gear.

These findings highlight not only technological skill but also cultural diversity: northern and southern communities employed different knotting methods, thread twists, and mesh sizes. Such details reflect regional traditions and material choices, not just practical needs.

The Cost of Crafting Nets

Reconstructing the nets also revealed the immense labor behind their creation. One net, reconstructed from impressions in Hokkaido pottery, would have required at least 85 hours of skilled labor, not including the time spent preparing plant fibers. In practical terms, making a fishing net could consume over 10 days of work. Given this investment, nets were far too valuable to discard. Instead, they were reused in pottery production once they had outlived their original purpose.

This cycle of reuse demonstrates an early awareness of resource conservation—an ethos that resonates with today’s emphasis on sustainability. Nets in Jomon society were not disposable commodities but treasured tools that continued to serve long after their fishing days ended.

Knots, Twists, and Cultural Identity

The study also highlights subtle but telling differences in craftsmanship. In Hokkaido, nets were made with S-twisted threads tied with reef knots, a style that produced strong but slightly unstable meshes. In contrast, Kyushu nets used Z-twisted threads tied with simple overhand knots. These variations point to cultural traditions in thread-making and knot-tying that were as significant as regional dialects or pottery styles.

Interestingly, the researchers compared their findings to ethnographic records, noting that similar knots and thread twists appear in prehistoric sites across Asia and northern Europe. This suggests broader networks of knowledge and shared techniques across ancient communities.

Technology Reviving the Past

What makes this study particularly remarkable is the method. By combining high-resolution CT scanning with silicone casting, archaeologists transformed faint impressions into detailed three-dimensional reconstructions. This allowed them to identify thread thickness, knot types, and even calculate net dimensions.

Beyond fishing nets, this methodological breakthrough opens possibilities for analyzing other fiber-based artifacts worldwide. Pottery fragments from diverse cultures may contain hidden imprints of textiles, containers, or woven items long thought lost to decay.

A Complex Material Culture

The findings challenge the assumption that net impressions on pottery always represent fishing gear. Instead, nets were versatile, serving as fishing tools, storage containers, molds, and structural reinforcements. This versatility reflects a dynamic material culture where objects moved fluidly between domains of daily life—food gathering, crafting, and resource management.

A Legacy of Innovation and Sustainability

By resurrecting the lost nets of the Jomon period, researchers not only revealed ancient fishing technology but also illuminated broader cultural values. These prehistoric communities were resourceful, inventive, and attentive to sustainability. Their practices remind us that the principles of reuse and adaptation—so crucial in addressing today’s environmental challenges—have deep roots in human history.

As archaeologists continue to apply advanced imaging technologies, more hidden stories may yet be uncovered, offering fresh insights into how ancient societies thrived by making the most of their resources.

Obata, H., & Lee, Y. (2025). Nets hidden in pottery: Resurrected fishing nets in the Jomon period, Japan. Journal of Archaeological Science, 179, 106231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2025.106231

Cover Image Credit: Irie-Takasago Shell Midden fish hooks.