In Vietnam’s central Ha Tinh province, archaeologists have uncovered a remarkable concentration of ancient artifacts beneath rice fields in the mountainous border commune of Son Kim 2. The discoveries, made in the Lang Che area after local farmers reported unearthing unusual objects during fieldwork, are helping researchers trace thousands of years of continuous human settlement in western Ha Tinh — a region historically shaped by trade routes, upland agriculture, and cultural exchange.

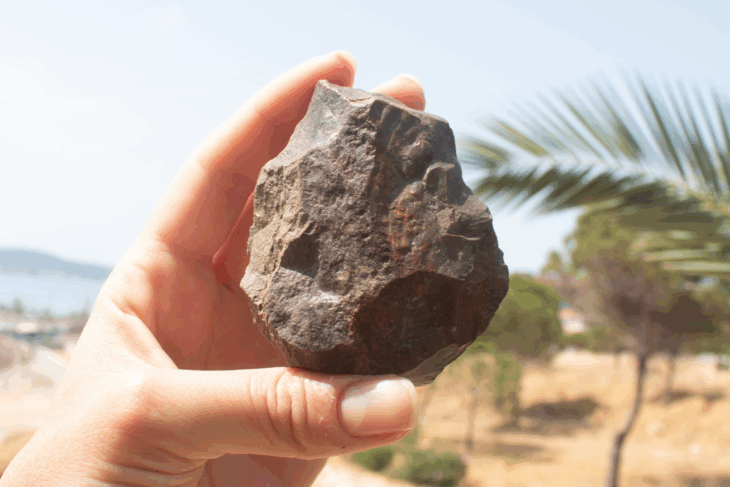

A field survey conducted by the Ha Tinh Museum documented an array of artifacts spanning prehistoric, early-historic, and feudal periods. Among the first items recovered were bronze bells, stone chisels, ceramic bowls, and iron swords and blades — objects that clearly belonged to different eras and everyday contexts. Further exploration revealed even more: stone axes and pestles, grinding slabs, iron and bronze tools, fragments of coarse household pottery, and highly valuable ceramics dating to the Tran Dynasty (1225–1400), one of the key political periods in medieval Đại Việt.

Researchers say the finds cluster across roughly one hectare of terraced farmland, indicating that the site likely functioned as both a habitation area and a small production zone for early mountain communities. Hundreds of fragments of coarse earthenware and celadon-glazed pottery were scattered around the ruins of the Sơn Thần shrine — an abandoned site of ancestral and nature worship. This combination of artifacts and sacred space suggests that residents not only built homes and tools here, but also formed early folk belief traditions closely tied to the surrounding forests and highland landscape.

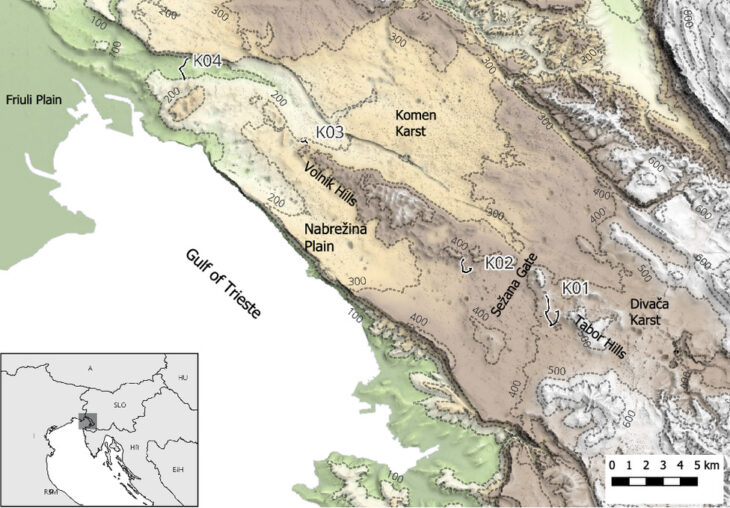

From an archaeological perspective, the Lang Che discoveries deepen the narrative of Ha Tinh’s western frontier. Situated along the eastern slopes of the Truong Son (Annamite) Range and historically connected to trans-mountain routes linking northern and central Vietnam with neighboring Laos, the area has long been a cultural crossroads. Evidence of stone tools points to prehistoric settlement patterns, while later metal artifacts and ceramics reflect technological transitions and social development through successive periods. The presence of Tran-era pottery, in particular, corresponds to a time when Đại Việt expanded population centers outward from lowland deltas into upland valleys, forming new villages along riverbanks and ridge lines.

Experts note that the diversity of materials — from stone and bronze to iron and glazed ceramics — illustrates cultural continuity rather than isolated occupation. Instead of a single settlement episode, the layers of relics indicate that different communities adapted the same landscape over millennia, inheriting, exchanging, and reshaping local traditions. This continuous human footprint aligns with broader archaeological patterns seen across north-central Vietnam, where mountain foothills served as both refuges and resource zones during periods of migration and state consolidation.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

For the Ha Tinh Museum, the survey not only expands its collection of scientifically valuable artifacts, but also creates a foundation for future excavation, conservation planning, and heritage interpretation in Son Kim 2. Museum representatives emphasize that systematic research in the area could clarify settlement chronology, reveal long-term subsistence practices, and help protect the site from modern development pressures. The findings also underline the importance of community participation: it was local farmers — working rice fields that have supported generations — who first recognized and preserved the unusual objects that led to the investigation.

Beyond academic significance, the discovery strengthens the cultural identity of western Ha Tinh’s mountain communities. By documenting tangible links to ancient craftsmanship, ritual spaces, and everyday life, the project highlights how present-day residents are custodians of a landscape layered with memory. With careful protection and thoughtful public engagement, the newly documented site in Lang Che may one day become a reference point for regional heritage tourism and education — connecting today’s visitors with the deep past beneath Vietnam’s rice fields.

Cover Image Credit: BHT