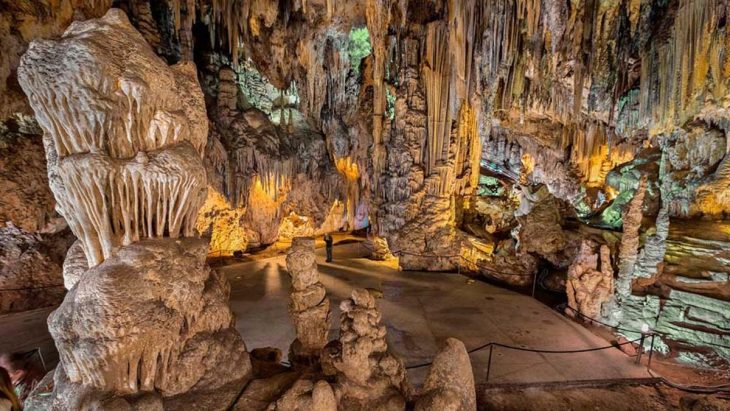

An extraordinary discovery in a Romanian forest near the hill of Măgura Călanului has unveiled a unique set of 15 iron stonemasons’ tools from the pre-Roman Iron Age. Unearthed in an ancient limestone quarry at Măgura Călanului, this remarkable find offers an unprecedented glimpse into the stoneworking techniques of the Dacian civilization before the Roman conquest.

The extraordinary find occurred in the summer of 2022 when a local villager stumbled upon the collection at the base of a tree near the main quarry face. The tools, weighing a substantial 25 pounds, appeared to have been recently dug up and abandoned, possibly by looters whose plans were thwarted by the sheer weight of their illicit haul. The finder promptly reported the discovery to the Corvin Castle Museum in Hunedoara.

While the removal from their original context makes precise dating challenging, the toolkit contains tool types unequivocally associated with the Dacian kingdom, which flourished between the 2nd century B.C. and 106 A.D. Furthermore, the quarry itself bears the telltale marks of tool usage that ceased entirely after the Roman withdrawal in the mid-3rd century A.D., further suggesting a Dacian origin for the implements.

The diverse collection comprises five double-headed picks, including two rare examples with toothed edges, five splitting wedges of varying sizes designed to break apart large stones, a whetting hammer and field anvil used for sharpening chisels, and single examples of a flat chisel and a point, likely used for intricate finishing work. This assemblage represents a comprehensive range of stonemasonry techniques, from direct percussion using the picks to indirect percussion with the chisel and point, cold sharpening with the hammer and anvil, and the force of stone-splitting wedges.

Intriguingly, the double-headed picks with toothed edges appear to be a uniquely Dacian design, with no known counterparts in either Greece or Rome. Researchers believe these specialized toothed sides were instrumental in achieving the refined finish of the prismatic blocks characteristic of the luxurious ashlar architecture of the Dacian period.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

While splitting wedges were common in ancient construction and quarry sites across the Greco-Roman world, the examples found in this toolkit are notably small, weighing between 150 and 400 grams. This suggests they were intended for use on smaller stone blocks or the relatively softer limestone of the Măgura Călanului quarry, requiring less force to create the necessary fissures. Evidence within the quarry itself supports this, with partially split stones still bearing the uniform-sized and depth splitting sockets. This uniformity hints at the possibility that the toolkit belonged to a master mason who possessed a range of wedge sizes and potentially delegated splitting tasks to work teams equipped with matching wedges. Alternatively, the discovered set might be incomplete, with some tools either deliberately buried elsewhere or lost during their recent, unrecorded excavation.

The inclusion of a whetting hammer, commonly used for sharpening agricultural tools like scythes and found at Romanian farm sites, alongside a much rarer field anvil, with comparable examples only known from Roman Britain and Gaul (also associated with scythe sharpening), is particularly significant. This marks the first instance of such tools being discovered in a quarry context. Their presence suggests that Dacian stonemasons maintained their tools’ sharpness directly at the worksite, a crucial practice given how quickly chisels and points would dull. This on-site sharpening capability would have allowed for continuous work without the need for frequent trips to a blacksmith.

The predominantly small size of the tools indicates a focus on finishing work, which in a quarry setting would involve splitting smaller blocks and refining rough surfaces for both construction and decorative elements. The unique limestone extracted from the Măgura Călanului quarry was even transported over 25 kilometers across challenging terrain to build the impressive walls and towers of Dacian fortresses, including the UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Sarmizegetusa Regia. The extensive 30-hectare quarry itself bears witness to a sudden abandonment, likely due to the Roman conquest around 102 A.D., with numerous tool marks, semi-finished blocks, and stone debris scattered across the site. Modern LiDAR technology has allowed scientists to map the quarry’s vastness and complexity.

The study of the hidden toolkit raises compelling questions about why it was buried. One theory suggests it was concealed during a period of crisis, possibly the Roman invasion. Another possibility is that the stonemason simply sought to avoid the burden of transporting the heavy tools daily but was ultimately unable to retrieve them Despite some discernible Roman influences in certain tool designs, research leans towards the toolkit belonging to a Dacian stonemason. The quarry appears to have been inactive during the Roman era, and the design of specific tools deviates from known Roman patterns. Furthermore, the cessation of carved stone architecture in the region following the Roman conquest supports a pre-Roman origin.

The remarkable discovery at Măgura Călanului significantly enriches our understanding of stonemasonry in Dacia, challenging existing assumptions about construction and quarrying practices in the region. It also opens avenues for future research, with the potential to connect these tools to the tool marks observed on the quarry faces and stones. Metallographic and microstructural analyses, along with use-wear studies, could further illuminate the manufacturing techniques and practical application of these iron tools by Dacian craftsmen, providing an even more detailed picture of their ancient skills.

Pețan, Aurora. “A stonemason’s toolkit from the pre-Roman limestone quarry at Măgura Călanului (Romania)” Praehistorische Zeitschrift, 2025. doi.org/10.1515/pz-2025-2011

Cover Image Credit: Aurora Pețan