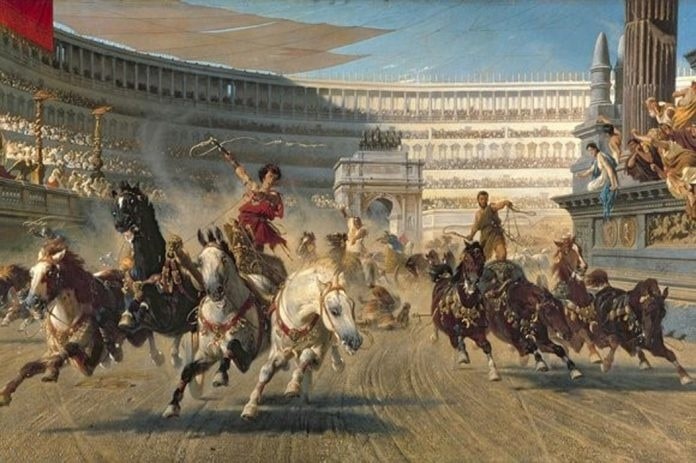

Chariot racing “ludi cirenses” was one of the indispensable sports for the Roman and Byzantine Empires. The days on which Ludi’s the days it was held were considered holidays and no one would work that day. It was a part of festivals and religious holidays.

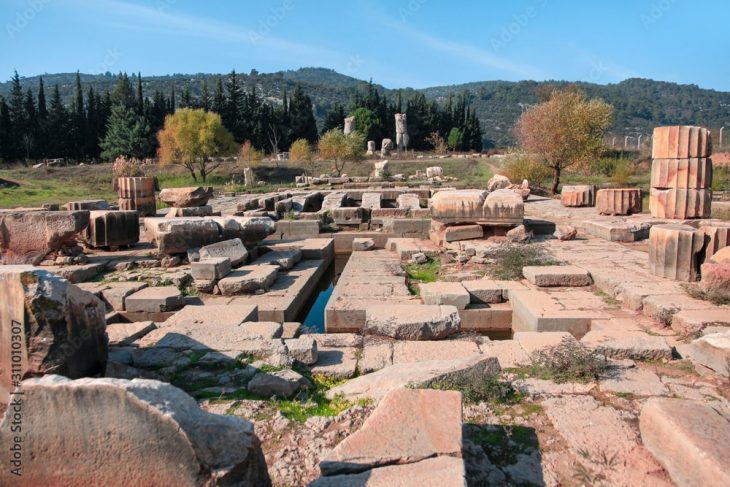

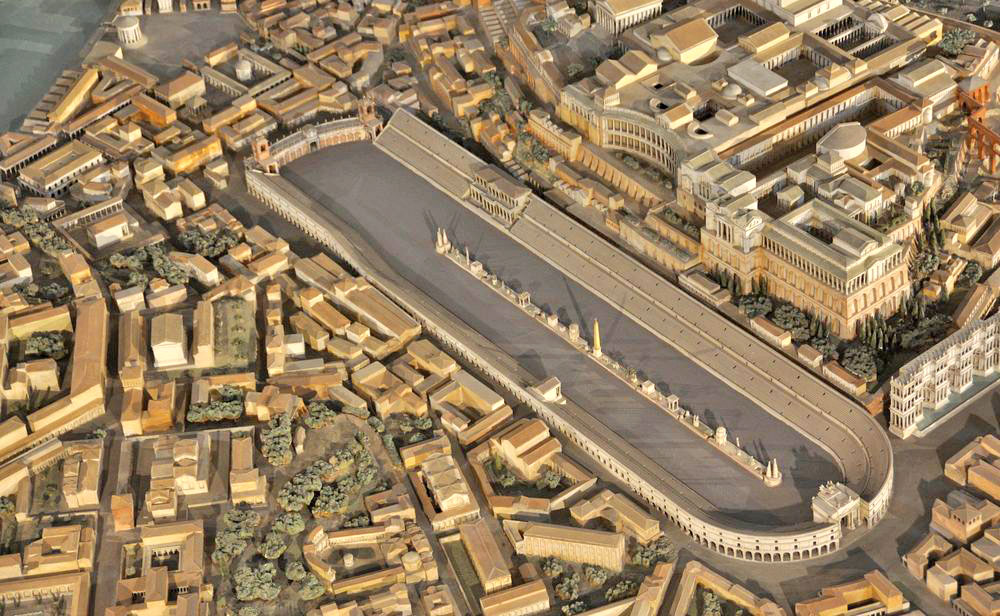

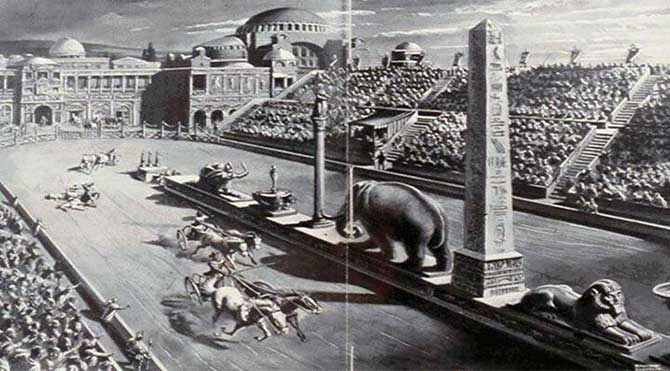

Ludi cirenses, so chariot racing, although imitated from Etruscan and ancient Greek civilization, was undoubtedly developed in the Roman Empire. They also transformed Greek hippodromes into great circuses. Circus Maximus in Rome was the most important and the largest of these circuses.

The sand track that started in the U-shape between the Aventinus and Palatinus hills was replaced by a large stone building with a seating capacity of 250,000.

The race itself was quite simple: twelve chariots would wait at the starting point, and when the organizer dropped a white Mappa (handkerchief), the rope at the starting point would be pulled. They had to race seven rounds, symbolized by seven eggs and seven dolphins in the “Spina”. When a tour is complete, an egg was being taken. During the race, drivers could do anything. They could try to push each other ‘spina’ (spines in the center) or simply choose to race each other, but they could also hit each other using their whips instead of horses. There have been many accidents this way, and most Chariot drivers have not had a long life as a result.

Racers had represented by different colors. They caused quite violent scenes among those who held them. These colors created rivalry among audiences and often led to violence among supporters of rival groups. And the races became more and more politicized.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

With the collapse of the Roman empire, it nearly has faded in the races. The Byzantine Empire, on the other hand, viewed races as a way of consolidating social class and political power and was an effective event for the Emperor to bring his subjects together for the celebration.

In AD 447-448, Constantinople’s and Theodosian walls were badly damaged by a series of earthquakes. The city was already under the threat of invasion by the Huns led by Attila.

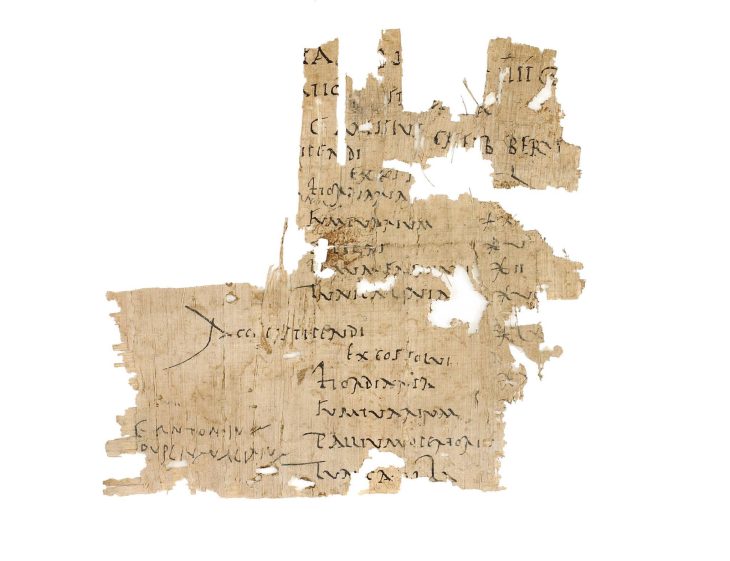

I. Theodosius ordered the praetorian governor Constantine Flavius to quickly repair the walls (previously it took nine years to build). Realizing the enormous task ahead of him, Constantine Flavius reached out to groups of chariot crews for help and gathered a workforce of about 16,000 supporters.

He managed to channel the spirit of car racing to Governor Konstantin Flavius to the team here. Each faction was given a piece of wall based on the competitive procedure to complete its divisions before the other and win the glory of their team. The “Blue” team worked on the walls stretching from the Blakherna Gate to the Myriandrion Gate and from the “Greens” Myriandrion Gate to the Sea of Marmara. In just sixty days, the great walls of Constantinople were restored and the defensive moat cleared of debris.

During this period, the Huns captured more than 100 cities and had translated their direction to Constantinople. The people, who saw Constantinople in danger, had begun to flee from the city.

Hearing that the walls were completed, the Huns abandoned their plans to conquer Constantinople and instead turned their attention further west, to the Balkans, which had taken over many Byzantine cities and settlements. Theodosius preferred to remain silent for peace. The Hun Emperor Atilla left to occupy the former lands of the from here Western Roman Empire.

Ludi literally means a game organized for the benefit and entertainment of the public.

Source

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/circusmaximus/circusmaximus.html