In a chilling archaeological discovery, researchers have uncovered direct evidence that a child was decapitated and cannibalized approximately 850,000 years ago by members of the now-extinct early human species, Homo antecessor. The find, unearthed at the Gran Dolina site in Spain’s Sierra de Atapuerca, adds a new layer to our understanding of prehistoric human behavior — particularly in relation to violence, survival, and social norms.

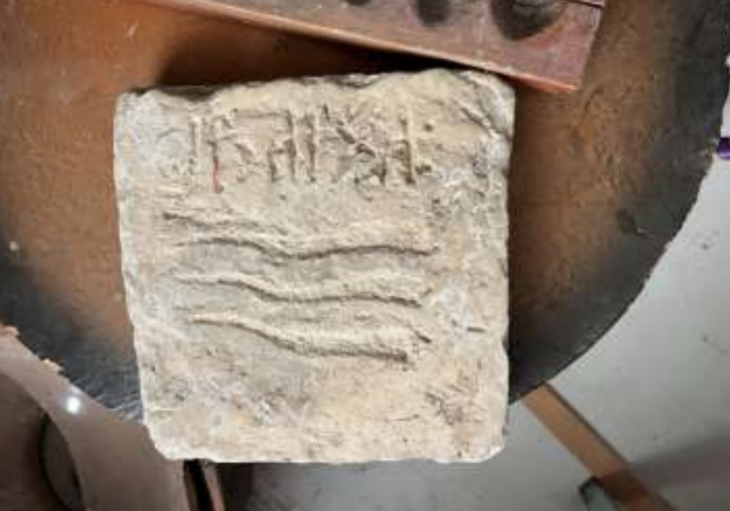

The evidence centers around a small human cervical vertebra belonging to a child estimated to be between two and four years old. According to the research team from IPHES-CERCA, the bone showed unmistakable cut marks at precise anatomical locations, indicating intentional decapitation. The incisions align with methods used for disarticulating the head — similar to how early humans processed animal prey for consumption.

“This case is particularly striking, not only because of the child’s age, but also due to the precision of the cut marks,” said Dr. Palmira Saladié, a specialist in taphonomy and prehistoric cannibalism and co-director of the Gran Dolina excavation. “The vertebra presents clear incisions at key anatomical points for disarticulating the head. It is direct evidence that the child was processed like any other prey.”

This vertebra is one of ten newly uncovered human remains at archaeological level TD6, all attributed to Homo antecessor, a species that lived in Western Europe between 1.2 million and 800,000 years ago. Several bones from the site exhibit telltale signs of defleshing and intentional fracturing — indicators that they were processed for food, just like the remains of animals found at the same level.

Although disturbing, this discovery is not entirely unprecedented. Nearly three decades ago, the same level at Gran Dolina yielded the world’s first documented case of prehistoric human cannibalism. What makes this recent find significant is the consistency it reveals: a pattern of repeated behavior rather than an isolated act. “The treatment of the dead was not exceptional, but repeated,” Saladié explained.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The researchers believe cannibalism among Homo antecessor may have served multiple purposes beyond mere sustenance. The exploitation of human flesh could have functioned as a form of territorial control or dominance, particularly in an environment characterized by intense interspecies competition. This theory gains traction from additional discoveries made during the same excavation season — most notably a hyena latrine containing over 1,300 coprolites (fossilized dung), located just above the layer containing human remains.

The stratigraphic overlap between human bones and hyena excrement helps scientists reconstruct the dynamics of cave occupation during the Lower Paleolithic. It paints a picture of a harsh, competitive landscape where carnivores and humans alternated control of the space, likely scavenging or driving each other out in cycles of survival.

Beyond the implications for understanding cannibalism, this discovery provides valuable insight into the life — and death — of early humans in prehistoric Europe. The presence of juvenile remains raises questions about vulnerability, social structures, and the decision-making processes within early human groups.

“Every year we uncover new evidence that forces us to rethink how they lived, how they died, and how the dead were treated nearly a million years ago,” Saladié concluded.

The findings from Gran Dolina underscore how much remains to be learned from ancient remains buried deep in prehistoric sediments. As excavations continue, scientists hope to further unravel the complex, and at times unsettling, realities of early human behavior.

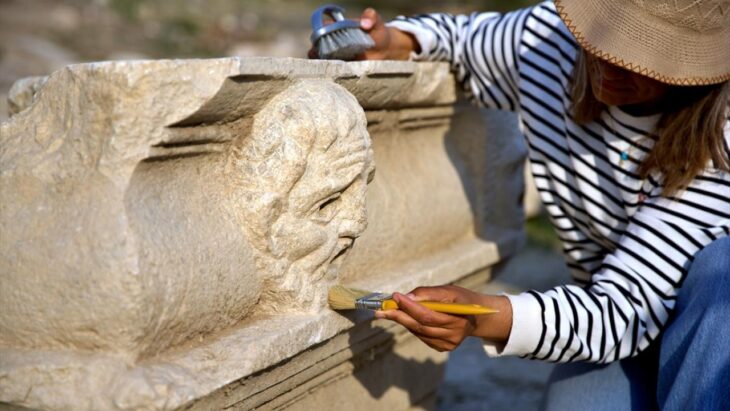

Cover Image Credit: Maria D. Guillen/IPHES-CERCA