For centuries, the strength of the Roman Empire has been explained through its armies, its roads, and its conquests. Histories have traditionally pointed west to Hispania or north to Dacia when discussing the metals that sustained Rome’s economy. Yet beneath the forested mountains and rugged valleys of the Central Balkans lay a quieter, less visible source of imperial power—one that modern scholarship is only now beginning to fully recognize.

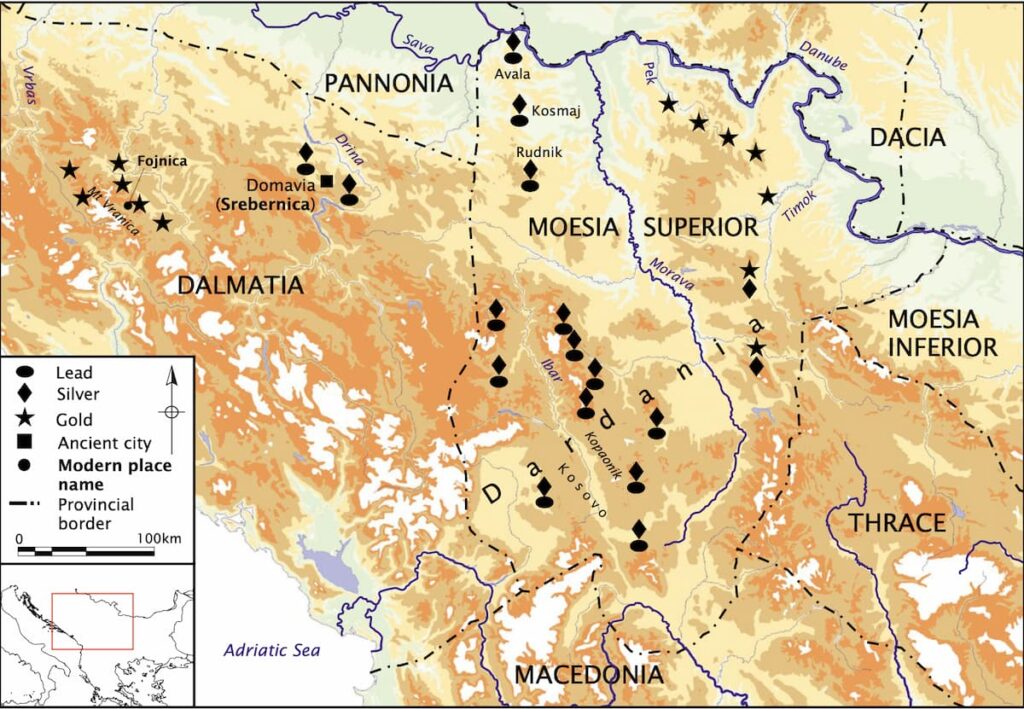

New archaeological research suggests that the territories of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Kosovo were not marginal frontier zones, but a deeply integrated industrial heartland that supplied Rome with critical resources over more than two centuries. Far from operating on the empire’s periphery, these regions played a central role in stabilizing Roman finances during periods of expansion, crisis, and transformation.

Published in the Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, a recent study by archaeologist Dragana Mladenović challenges long-standing assumptions about where Rome’s economic strength truly came from. By shifting attention away from traditionally emphasized mining centers and toward the Central Balkans, the research reveals how geography, technology, and direct imperial control combined to turn this rugged landscape into one of the empire’s most strategically important regions.

This reinterpretation does more than relocate a source of wealth on the map. It forces a reassessment of how the Roman state managed resources, responded to economic pressure, and quietly reinforced its power from below—through infrastructure carved into mountainsides, labor organized across provinces, and extraction systems designed for scale, efficiency, and control.

Why the Balkans Remained in Rome’s Shadow

The Balkans’ long absence from the spotlight was not accidental. Roman administrative boundaries rarely align with modern ones, complicating attempts to reconstruct mining zones as coherent systems. Written sources, often favored by historians, mention Iberia and Dacia far more frequently than the Balkan interior, giving the impression that silver production there was secondary. Archaeology, meanwhile, has faced serious obstacles: steep terrain, forested mountains, and areas still affected by the legacy of the 1990s conflicts have limited sustained fieldwork.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

According to Mladenović, these factors combined to create a distorted picture in which visibility was mistaken for importance. Where evidence was fragmentary or erased by later activity, silence replaced recognition.

Dalmatia: Hydraulic Mining and the Reshaping of Landscapes

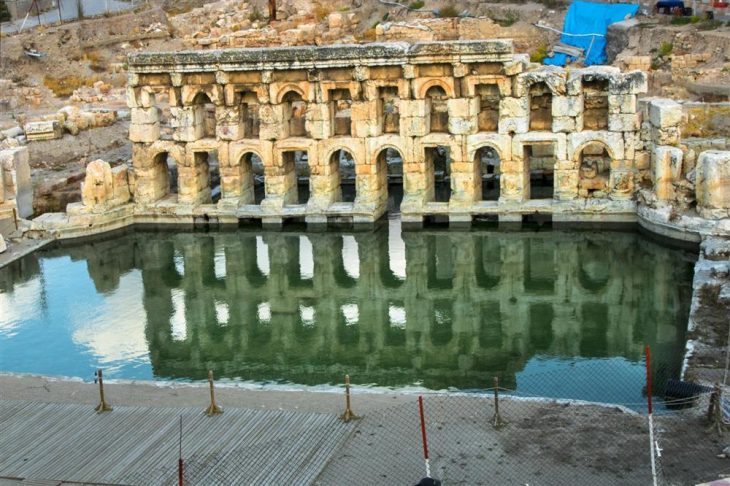

When the archaeological record is examined more closely, a different image emerges. In the Roman province of Dalmatia, particularly in central Bosnia, the empire exploited both gold and silver using remarkably advanced techniques. Hydraulic mining reshaped entire mountain slopes as vast quantities of water were collected in reservoirs and released through channels to wash away soil and expose ore-bearing layers.

These methods left permanent scars on the landscape—sterile gravel mounds, trenches, and artificial valleys—some of which are still echoed in local place names. Nineteenth-century Austro-Hungarian engineers described hillsides riddled with pits and long cuts stretching for hundreds of meters. Modern surveys confirm that these accounts were no exaggeration but rather evidence of industrial-scale exploitation.

Upper Moesia: Underground Silver and Roman Engineering

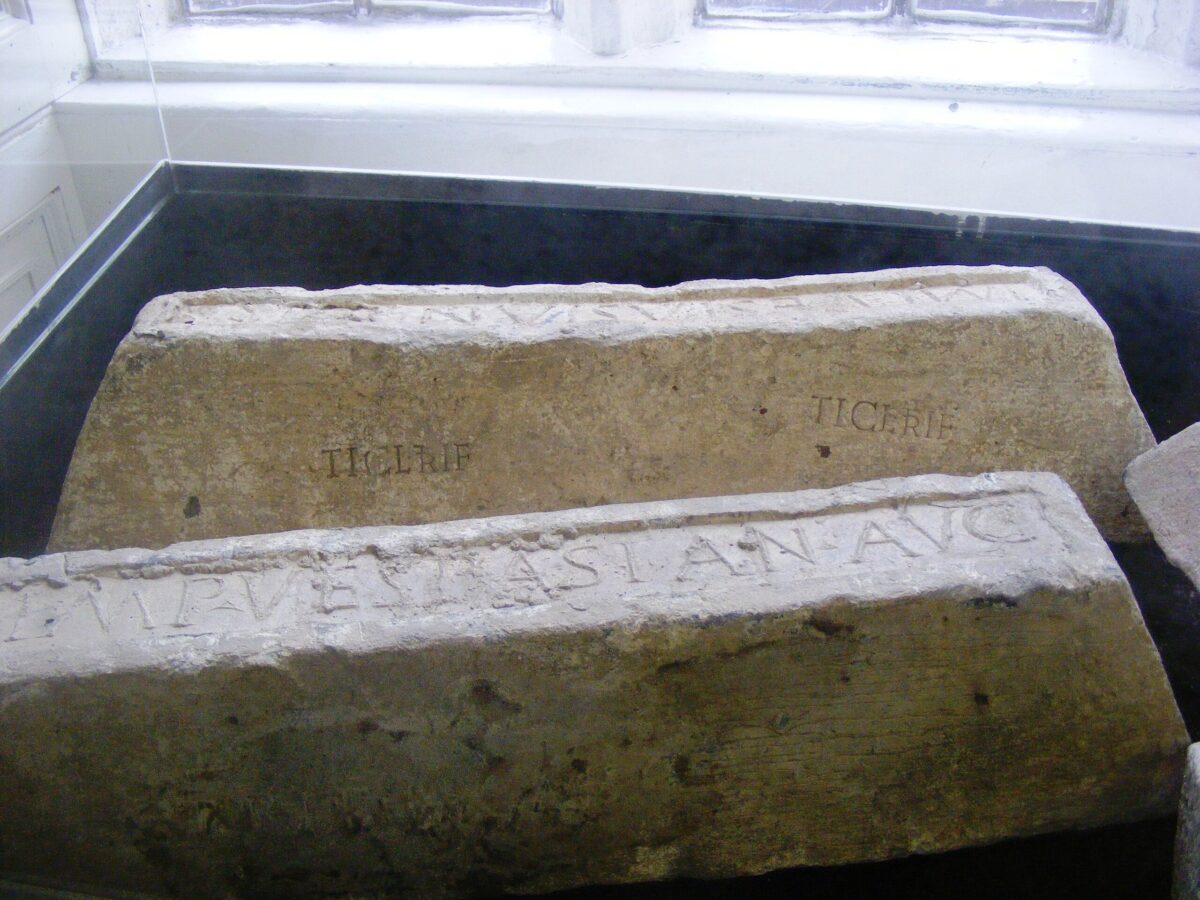

Further east, in Upper Moesia—covering parts of modern Serbia and Kosovo—the focus shifted to silver extracted from argentiferous galena. Here, Roman miners worked underground on a massive scale. In Domavia, near today’s Srebrenica, later engineers encountered ancient galleries so carefully carved that they resembled subterranean buildings rather than simple mines.

Lamp niches, drainage systems, and widened passages reveal not only technical sophistication but also a high level of labour organisation. These features suggest continuous operation over long periods, supported by administrative planning and logistical coordination.

Dardania and the Paradox of Vanishing Evidence

The paradox of the richest Balkan districts lies in their apparent archaeological silence. In Dardania, particularly around sites such as Novo Brdo and Trepča, centuries of medieval and early modern mining all but erased Roman-era traces. Historical sources describe enormous slag heaps and thousands of ancient shafts, yet little remains visible today.

Mladenović emphasizes that this absence should not be misread as proof of Roman inactivity. On the contrary, the very intensity of later exploitation likely destroyed the evidence of earlier phases. In this case, silence in the ground may signal extraordinary continuity rather than neglect.

Kosmaj: Where Numbers Finally Speak

The most compelling quantitative data come from Mount Kosmaj in Serbia. Unlike other regions, mining here was limited to the Roman period, with no significant medieval reuse. This allows archaeologists to isolate Roman activity with unusual clarity.

Estimates suggest that at least 2.3 million tons of slag were produced in this single district. From this volume, researchers calculate the extraction of approximately 5,500 tons of silver and 680,000 tons of lead. The implied annual silver output—around 22 tons—rivals that of Laurion, the famed mining district that fueled classical Athens.

High-Temperature Furnaces and Industrial Refinement

Technological analysis reinforces the scale of production. Lead ingots found in the region are exceptionally large, some weighing more than 250 kilograms, pointing to powerful high-temperature smelting furnaces capable of sustained output.

Equally striking is the efficiency of silver refinement through cupellation. The uniformity of the results suggests that much of the silver left the region already purified to imperial standards. This implies a division of labor within the production chain and a level of quality control more typical of centralized industry than frontier extraction.

An Empire That Chose Direct Control

Perhaps the most provocative conclusion of the study concerns administration. According to Mladenović, the Balkan silver mines were not loosely regulated enterprises but direct imperial property, overseen by equestrian procurators. Leasing to private contractors appears to have been minimal, contrasting sharply with practices in parts of Hispania.

Military presence reinforced this control. New cohorts were established specifically to guard mining districts, while river routes remained heavily garrisoned long after their frontier role had ended. A dense network of customs stations monitored the movement of metal, creating one of the most tightly supervised extractive zones in the Roman world.

Silver, Crisis, and the Survival of the Empire

The timing of Balkan intensification is no coincidence. From the late second century onward, major silver sources in Hispania declined, while Dacia’s gold mines were abandoned amid invasions. As western supplies faltered, metallurgical activity in the Central Balkans surged.

This silver sustained the empire during the political and monetary crises of the third century. The rise of emperors from the Danubian regions, the relocation of mints closer to Balkan sources, and continued investment under Constantine all point to the strategic value of these mines.

Strengths and Limits of a New Interpretation

The study’s strength lies in its synthesis of archaeology, landscape analysis, and metallurgical data, offering rare quantitative estimates and a coherent administrative model. It convincingly explains why some of the richest regions appear archaeologically silent and reframes the Balkans as a core, not peripheral, zone of imperial power.

At the same time, limitations remain. Some areas are still difficult to access, forcing reliance on indirect evidence and historical accounts. Claims about the Balkans as the primary silver supplier must ultimately be tested against equally comprehensive data from Hispania and other regions.

Even so, Mladenović’s work represents a major shift in perspective. It reminds us that Rome’s power was not sustained only by conquests and legions, but by the silent, relentless extraction of wealth from beneath the mountains—where the empire’s true silver backbone may have lain all along.

Mladenović, D. (2025) Roman Gold and Silver Mining in the Central Balkans and Its Significance for the Roman State, Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, 140, pp. https://doi.org/10.34780/g6w4-86u6

Cover Image Credit: Public Domain