Medieval sources blur the line between history and legend — but new archaeological evidence suggests that one of the Viking Age’s most formidable figures may have been laid to rest beneath a coastal hill in England.

For more than a thousand years, the final resting place of Ivarr the Boneless has remained one of the Viking Age’s most enduring mysteries. Now, a windswept hill on England’s north-west coast may offer the strongest archaeological lead yet.

An archaeologist working in Cumbria believes that a large, carefully shaped mound overlooking the Irish Sea could conceal the ship burial of the infamous Viking war leader—a man who reshaped early medieval Britain before vanishing from the historical record without a confirmed grave.

If the theory proves correct, the site would represent the first monumental Viking ship burial ever identified in the United Kingdom, and one of only a handful known across north-west Europe.

A mound known as “The King’s Hill”

The hypothesis comes from archaeologist Steve Dickinson, who has spent years comparing archaeological evidence with medieval textual sources. His focus is a prominent mound mentioned in early records under the name Coningeshou—a term widely interpreted as “The King’s Mound.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Located near the Cumbrian coast, the mound measures roughly 60 meters in diameter and six meters in height, dimensions consistent with elite burials from the Viking world. Its exact location remains undisclosed to prevent looting or disturbance.

Dickinson argues that repeated references to Coningeshou in Icelandic saga material, combined with the mound’s scale and coastal position, point toward a royal burial rather than a natural formation.

Speaking to the BBC, Dickinson said the discovery could indicate a previously unknown Viking necropolis along the Cumbrian coast, potentially reshaping how Viking presence in north-west England is understood.

What makes the site especially compelling is its broader landscape. Surrounding the main mound are dozens of smaller burial mounds, which may represent an honor guard of warriors, retainers, or family members—an arrangement seen at other high-status Viking cemeteries.

Material clues beneath the soil

Although no excavation has yet taken place, non-invasive surveys and metal-detecting in the surrounding area have already produced intriguing results. Among the finds are large iron ship rivets and lead weights consistent with Viking-Age silver economies.

These artifacts do not prove the presence of a ship burial on their own, but they strongly suggest maritime activity and elite wealth in the immediate vicinity—exactly what would be expected near the grave of a ruler of Ivarr’s stature.

Later this year, Dickinson plans to conduct geophysical scans of the mound to determine whether a ship-shaped anomaly lies beneath its surface.

Who was Ivarr the Boneless?

Ivarr the Boneless was not a minor Viking raider. In the ninth century, he emerged as one of the most formidable military leaders in northern Europe, associated with the so-called Great Heathen Army that devastated Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

He is traditionally linked to the legendary Ragnar Lothbrok, though historians remain divided over whether this relationship was biological, symbolic, or purely literary. What is not disputed is Ivarr’s political impact: he played a central role in the Viking seizure of York and the transformation of Dublin into a Norse power base.

His fame has been renewed in popular culture through television dramas, but the historical Ivarr was likely more complex—and more enigmatic—than his fictional portrayals.

The mystery of “the Boneless”

Few Viking epithets have sparked as much debate as Ivarr’s. Medieval sources describe him as beinlausi—“boneless”—but what that meant in practical terms remains unclear.

Some scholars have proposed that Ivarr suffered from osteogenesis imperfecta, a rare genetic condition that causes fragile bones. Others argue that the name referred metaphorically to exceptional flexibility, ritual symbolism, or even naval skill, drawing on Old Norse linguistic nuances where “boneless” could imply fluidity or agility rather than disability.

A confirmed burial—especially one preserving skeletal remains—could offer the first opportunity to test these theories scientifically. Yet even if human remains are found, definitive identification would remain difficult without inscriptions or genetic comparison.

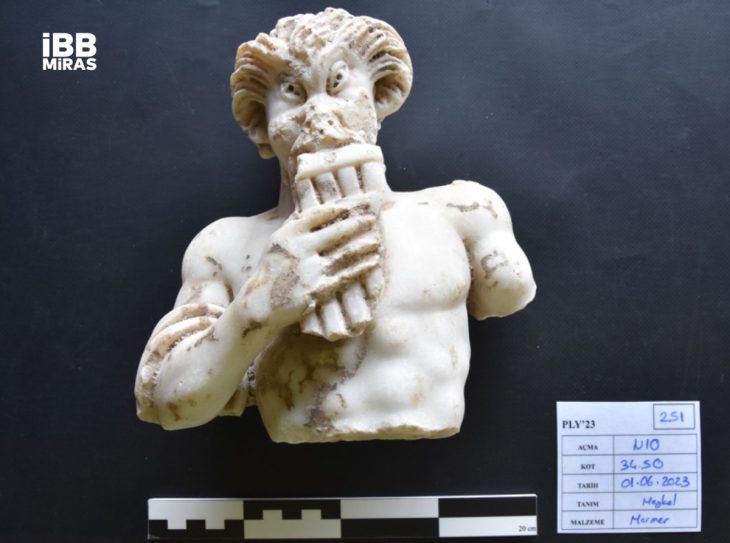

Metal ship rivets have been found in the area. Credit: Steve Dickinson

A burial fit for a ruler

Viking ship burials were reserved for society’s highest ranks. The deceased was laid within a vessel along with weapons, jewelry, regalia, food offerings, and sometimes sacrificed animals, before the ship was covered with earth to form a monumental mound.

The most famous British example of a ship burial is Sutton Hoo, an Anglo-Saxon site rather than a Viking one. A confirmed Viking equivalent in Cumbria would dramatically reshape understanding of Scandinavian power structures in early medieval Britain.

What comes next

Even if the mound does contain a ship, archaeologists caution against premature conclusions. Without inscriptions, absolute identification may remain elusive. Still, the discovery of a Viking ship burial on the Cumbrian coast—royal or not—would be a landmark event.

For now, the hill stands silent, overlooking the sea routes that once connected Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavia. Beneath it may lie answers not only about one legendary Viking, but about how power, belief, and memory were shaped in the Viking Age.

Whether Ivarr the Boneless truly rests there or not, the search itself is already transforming how historians map the Norse world in Britain.

Cover Image Credit: The top of the hill could contain a Viking ship and the remains of Ivarr the Boneless, according to archaeologist Steve Dickinson. Steve Dickinson