Archaeologists working at the site of El-Ahwat in northern Israel have uncovered the earliest known evidence of on-site bronze production in the southern Levant during the Iron Age I (ca. 1150–950 BCE). The groundbreaking study, published in PLOS One, reveals that local craftsmen were not merely recycling old metal, but producing bronze from raw copper and tin — a technological achievement previously undocumented in this region for the period.

The discovery challenges long-standing beliefs that bronzeworking in the early Iron Age was confined to lowland urban centers and limited to the re-melting of scrap. Instead, the findings suggest that even small, inland highland communities like El-Ahwat played a significant role in regional metallurgy, relying on complex trade networks that linked copper mines in the Arabah Valley with inland production hubs.

A Metallurgical Breakthrough

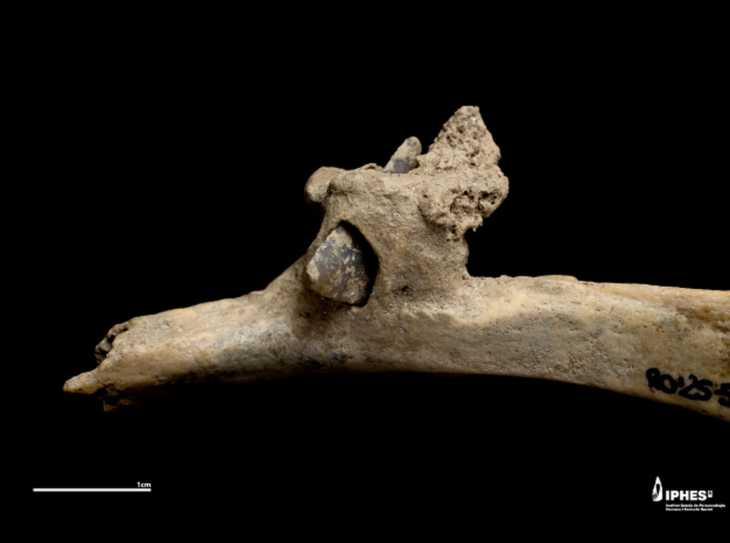

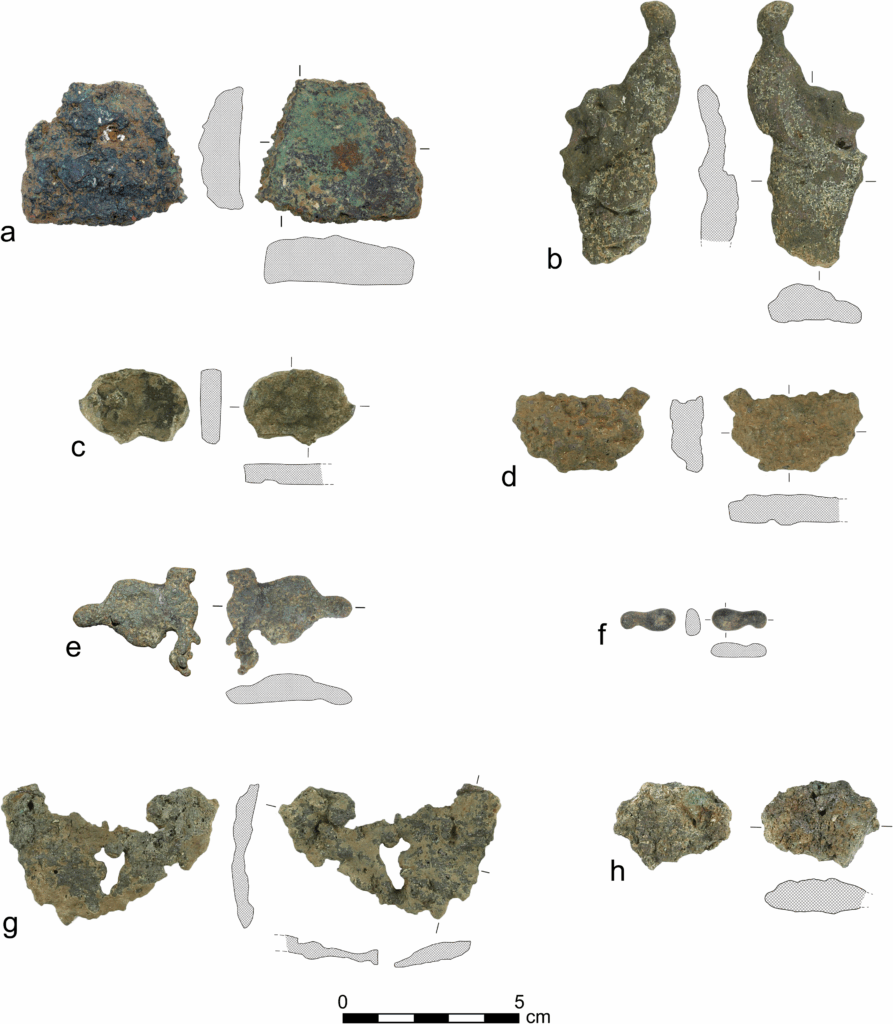

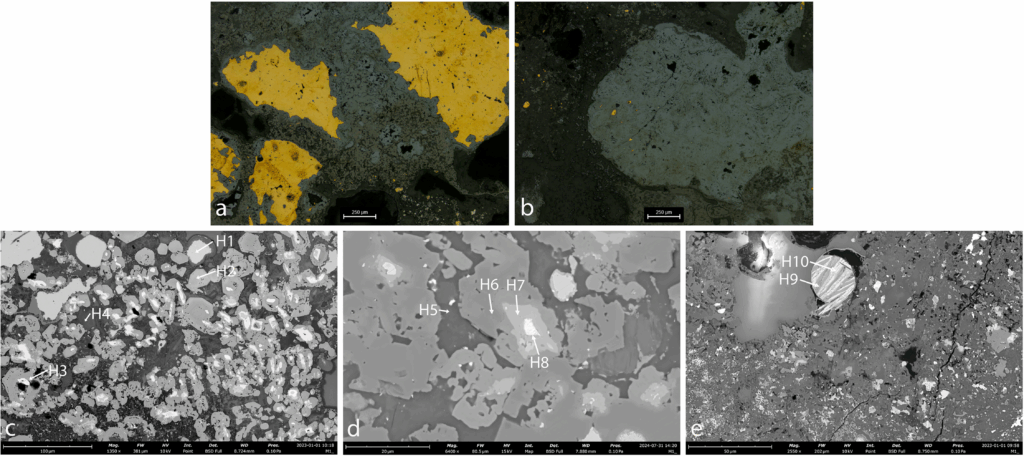

The research team, led by Dr. Tzilla Eshel of the University of Haifa, analyzed a unique assemblage of copper and bronze casting spills, slag fragments, and tools found at the site. Using optical microscopy, chemical analysis, and lead isotope testing, they identified clear signs of primary bronze production — the direct alloying of copper with tin.

Crucially, a tin-rich prill embedded in a slag fragment provided definitive proof that bronze was being made from raw materials on-site, rather than recycled. This makes El-Ahwat the first site in the southern Levant to yield unequivocal evidence of primary bronzemaking in the Iron Age I.

Copper from Two Ancient Mining Centers

Lead isotope analysis linked the copper to two major ancient mining regions: Faynan in modern-day Jordan and Timna in southern Israel. This dual sourcing is significant, as it indicates that El-Ahwat had access to both sides of the Arabah Valley, suggesting the existence of a coordinated supply system.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Some of the copper showed geological signatures unique to Faynan’s Dolomite Limestone Shale formations, while others matched Timna’s sandstone ores. The results hint that copper from both locations may have been mixed before being brought to the site — a sign of integrated political or economic control over the metal trade.

Implications for Trade and Politics

The study places El-Ahwat within a broader interregional network that moved raw copper from the mines to inland production centers and possibly to coastal ports. This contradicts earlier models that saw Arabah copper mainly exported directly to Egypt or the Mediterranean.

“This find forces us to rethink the economic and political landscape of the early Iron Age,” said Dr. Eshel. “It shows that inland communities were not passive recipients of finished goods, but active participants in the production process, with skilled artisans and access to strategic resources.”

The results also raise questions about who controlled the mines and the trade networks — whether Edomite groups, emerging Israelite polities, or other regional powers.

Technological Skill and Limitations

While the evidence confirms advanced metallurgical knowledge, the quality of the El-Ahwat bronze was uneven. Many metal spills contained high levels of impurities, such as copper sulfide and iron, suggesting inexperience or experimental production. Still, the ability to source tin — likely from distant, still-unknown origins — and alloy it locally demonstrates a high degree of organization and resource coordination.

A Window into Post–Bronze Age Resilience

The work at El-Ahwat offers a rare glimpse into how communities adapted after the collapse of Late Bronze Age empires around 1200 BCE. With centralized state systems gone, local groups developed their own supply chains and production methods, paving the way for the political entities — such as the Kingdoms of Israel, Judah, and Edom — that emerged in the following centuries.

The findings from El-Ahwat, alongside emerging evidence from sites like Tel Rehov and Tel Masos, suggest a thriving inland bronze industry during Iron Age I. This challenges the long-held notion of a technological “dark age” and instead highlights a period of innovation, adaptation, and expanding economic complexity.

As Dr. Eshel concludes, “Our study shows that even in a time of political upheaval, communities found ways to maintain and develop complex technologies, forging new paths for trade and craftsmanship that would shape the region’s history for centuries.”

Eshel, T., Bornstein, Y., Bermatov-Paz, G., & Bar, S. (2025). First evidence of bronze production in the Iron Age I southern Levant: A direct link to the Arabah copper polity. PLOS ONE, 20(8), e0329175. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0329175

Cover Image Credit: El Ahwat, looking north, during excavation season Sep. 2024. Aharon Lipkin