Excavations in Oberlöstern uncover burial mounds, villas, and monuments that blend Celtic and Roman traditions—tracing the roots of European identity.

In the quiet hills of Saarland, Germany, the past continues to resurface in unexpected ways. Near the small village of Oberlöstern, a district of Wadern, two monumental burial mounds stand as striking reminders of a world caught between two civilizations. Though constructed in the second century AD, these graves bear the unmistakable marks of both Celtic and Roman traditions—a cultural hybridity that reveals how local communities adapted to, resisted, and ultimately redefined life under Roman rule.

For more than a decade, archaeologist Professor Sabine Hornung of Saarland University has been leading an ambitious research project in this landscape. Her work not only uncovers traces of everyday life from 2,000 years ago but also sheds light on the broader processes of cultural transformation that shaped Europe itself.

A Landscape of Memory

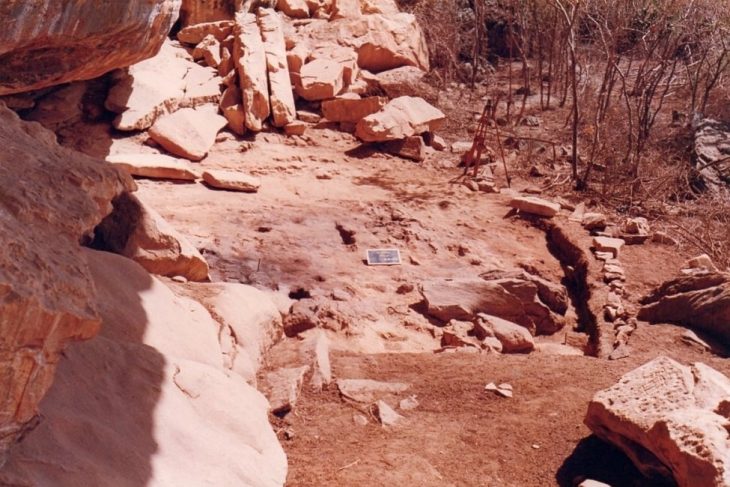

The two burial mounds, crowned with prominent stone pinecones—symbols of eternal life in Roman culture—were reconstructed in the 1990s using original materials unearthed during excavations. They are now visible landmarks, but Hornung stresses that they were never isolated monuments. Instead, they formed part of a much larger settlement landscape, one that included farmsteads, quarries, a villa estate, and even a temple precinct that once dominated the surrounding countryside.

By placing these mounds in their full context, Hornung and her team have pieced together a narrative of cultural negotiation. “Our findings provide insights into the lives of ordinary people, beyond what we know from history books,” she explains.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

From Celtic Hamlet to Roman Villa

Surface evidence of the ancient village has long since disappeared—“two millennia of agriculture have taken their toll,” Hornung notes. Yet geophysical surveys and excavations have brought remarkable discoveries to light. Beneath the soil lay the remains of a Celtic hamlet, a cluster of modest timber houses where several families lived together without clear social distinctions.

This picture changed dramatically after the Roman conquest. By the late first century AD, a landowning elite began to assert its power architecturally. Hornung’s team used geomagnetic prospection to reconstruct the largest Roman villa estate ever identified in the Hochwald region. The estate featured an impressive main building for the landowner, flanked by economic outbuildings and smaller dwellings for dependent families. “Here, social differences become visible in the architecture,” Hornung explains.

Cultural Hybridity in Stone

The burial mounds themselves speak volumes about identity in this transitional era. While their earthen form recalls traditional Celtic grave architecture, the stone enclosures and pinecone ornaments belong firmly to Roman funerary practice. Even more striking is a nearby funerary monument depicting a husband and wife in Celtic dress, though carved in Roman style.

“The monumental mounds are a cultural hybrid,” Hornung says. “Their builders emphasized their Celtic roots while also adopting Roman architectural elements. In this, we see a claim to ancestral land as well as a reflection of changing mentalities.”

Economic practices also reveal a stubborn continuity. The team identified nearby quarries where millstones had been produced since Celtic times. Although the local rock was inferior to imported lava stones available through trade, the community persisted in using and valuing its own materials—even for prestigious monuments. “It was almost a defiant statement,” Hornung suggests.

Linking Local and Global Histories

Hornung’s research in Oberlöstern is part of a broader investigation of cultural landscapes in Saarland. In 2010, she identified a Roman military camp at Hermeskeil—an important site for understanding Julius Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul. Together, these discoveries add pieces to the puzzle of how Celtic societies were integrated into the Roman world.

The implications, Hornung argues, extend far beyond regional tourism. “This was the time when sovereign Celtic tribes were incorporated into the Roman Empire, creating a political unity that laid the foundations of what we now call Europe,” she explains. By studying how ancient communities navigated cultural and political change, we may also glean lessons for today. “The challenges our societies face are not new. We can look back to see which strategies worked, and which failed.”

Bringing the Past to Life

Thanks to collaboration with the city of Wadern and support from Saarland’s Ministry of Economics and Environment as well as the Merzig-Wadern Cultural Foundation, the results of these studies are now accessible to the public. Information panels and 3D reconstructions allow visitors to imagine the grandeur of the villa estate, the prominence of the temple precinct, and the hybrid identity expressed in the burial mounds.

Standing among these reconstructed monuments, one can sense the weight of history. As Hornung observes, “When you imagine how the Roman estate once looked, or how the temple towered over daily life, you come closer to the people who lived here 2,000 years ago—closer than anywhere else.”

The story of Oberlöstern is not only one of local heritage. It is also a reminder that cultures rarely vanish overnight. Instead, they persist, adapt, and intertwine—leaving behind landscapes that embody resilience, negotiation, and the enduring complexity of identity.

Universität des Saarlandes (Saarland University)

Cover Image Credit: The monumental burial mounds of Oberlöstern combine Celtic and Roman traditions. Credit: Klaus-Peter Kappest / Saarland University