Archaeologists working at the prehistoric complex of Provadia–Solnitsata in Northeastern Bulgaria have uncovered a series of striking new findings, shedding light on mysterious construction rituals, unusual offerings to household spirits, and sophisticated building techniques dating back more than 7,000 years. The discoveries, reported by Academician Vasil Nikolov, head of the excavation team, mark one of the most intriguing archaeological seasons at the site to date.

A Monumental Burial Mound Concealing Ancient Secrets

This year’s fieldwork focused heavily on the massive burial mound that sits atop the prehistoric settlement. Rising approximately 13 meters in height and spanning roughly 80 meters at its base, the mound dates from the early Roman period. According to Nikolov, it likely consists of several smaller mounds that merged into a single monumental structure over time.

Although the team has yet to uncover burial complexes inside the mound, the 2024 season laid essential groundwork for next year’s excavations. Archaeologists plan to investigate two buildings in the northwestern section—structures attributed to a Thracian aristocrat who settled atop the prehistoric remains. These buildings, partly destroyed during Late Antiquity, feature stone foundations and sun-dried brick walls, and appear to have been remarkably luxurious for the time, with light-colored plaster interiors.

Fragments of fine Hellenistic pottery and richly filled ritual pits suggest that the Thracian nobleman was a wealthy figure, possibly involved in the region’s ancient salt-production economy—a hallmark of Solnitsata for millennia.

Peeling Back the Layers of a Prehistoric Urban Center

Beyond the Roman and Thracian-era features, the heart of the archaeological investigation remains rooted in the prehistoric layers beneath the mound. Solnitsata, dating from 5600 to 4350 BCE, is recognized as Europe’s oldest known salt-production center and is widely considered the first proto-urban settlement on the continent. Its fortified structure, multi-storey homes, and organized production zones set it apart as a highly developed prehistoric community.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

This season, excavations concentrated on the southern section of the prehistoric settlement, where archaeologists uncovered the remains of several two-storey buildings. One structure, distinguished by unusually deep foundation trenches, dates to the final phase of the Chalcolithic era, when climate instability led to the settlement’s abandonment.

“What’s truly fascinating,” Nikolov explained, “is the depth of the foundation trenches. You can clearly see the wooden postholes that supported the building. Although two-storey houses are known from the site, we had never encountered construction methods like this before.”

A Wealthy Salt Economy and Early Forms of Contracted Labor

Salt production was the settlement’s driving economic force, generating both wealth and cultural sophistication. The community—estimated at about 400 inhabitants—devoted most of its energy to producing, protecting, and trading this highly valuable resource. Archaeologists uncovered numerous artifacts, including finely crafted ceramic vessels, flint tools, and stone axes.

While some pottery was produced locally, Nikolov believes many pieces were commissioned from craftsmen in nearby communities since the salt producers themselves may have lacked time for additional artisanal work. The presence of hired laborers paid in salt challenges longstanding assumptions about the origins of wage labor. “This prehistoric society disproves the belief that paid labor began with capitalism,” Nikolov said. “Here we see a very early form of contracted workforce.”

Evidence of Conflict—and Strong Fortifications

Excavations also revealed arrowheads scattered throughout the settlement layers, suggesting repeated attempts by outsiders to seize Solnitsata’s profitable salt-production facilities. Yet there is no evidence that the settlement was ever successfully overtaken. The fortifications—massive stone walls and defensive structures—were among the earliest in Europe and played a key role in the community’s resilience.

These findings also point to the presence of at least two distinct family clans, each operating its own salt-production installation. This contributes to an evolving theory about the emergence of personal ownership: not private property in its modern sense, but early signs of individual or clan-based control over resources.

Mysterious Ritual Offerings to Household Spirits

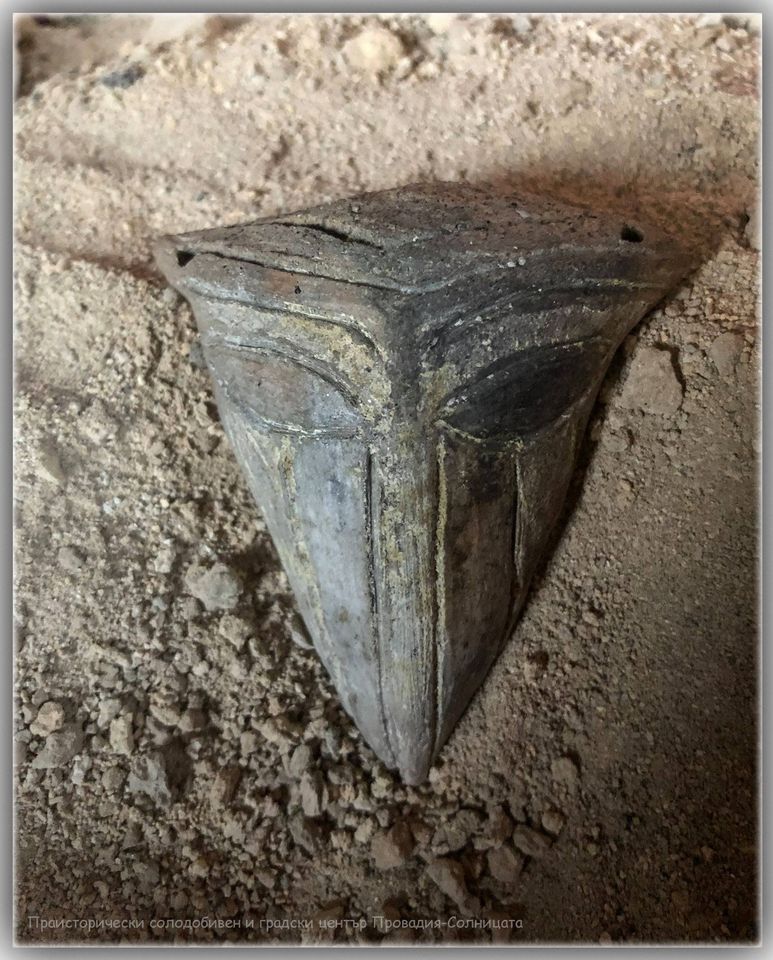

One of the season’s most captivating discoveries was the identification of multiple construction sacrifices dating to the mid-5th millennium BCE. Before erecting a home, prehistoric inhabitants performed ritual ceremonies designed to purify the space and ensure harmony with the protective household spirit of the dwelling. In a newly excavated house, archaeologists uncovered several unusual offerings placed beneath the floor—far more than what is typically found in a single structure.

Among the items were a deer skull accompanied by a horn, ceramic vessels, and a finely crafted flint axe, along with beautifully decorated pottery. In addition to these, the remains of a dog were discovered alongside more than twenty flint tools and several small stone chisels and axes.

The abundance of offerings remains a mystery, raising questions about the house’s social or spiritual importance. Even more unusual was evidence that the area had been ritually purified with fire—an uncommon practice for the region and period.

Another surprising find was a small clay figure built into the floor of a different house. Featuring a round head with ears and two holes resembling eyes, it has been humorously compared by archaeologists to a “prehistoric emoji.”

Advances in Prehistoric Art and Architecture

Archaeologists also uncovered traces of red ochre used for decorating pottery and walls. The material appears to have been ground, mixed—likely with water—and poured into molds to create chalk-like sticks for drawing.

One unsolved engineering puzzle involves how the ancient inhabitants constructed multi-storey houses capable of supporting heavy loads. A second-storey oven weighing over a ton was found last year, raising questions about the structural ingenuity of builders from 7,000 years ago. Modern engineers consulted by Nikolov have yet to provide a satisfying answer.

The team did, however, finally decode the purpose of peculiar round, bird-shaped vessels with spouts. Historical records of modern saltworks in Provadia revealed that these vessels were tools for pouring brine, essential in producing high-quality salt.

Solnitsata’s Growing Role in Europe’s Cultural Heritage

Today, Provadia–Solnitsata stands as a unique monument of European prehistory. Ongoing excavations are paired with efforts to conserve and publicly present the site, allowing visitors to experience the birthplace of Europe’s earliest urbanisation. According to Nikolov, Solnitsata is set to become part of the upcoming European Salt Heritage Route, a cultural corridor linking ancient salt-production centers in countries including Poland, Romania, Serbia, Hungary, Germany, France, and Italy.

If the project proceeds as planned, the route could be officially established within the next two years, further cementing Solnitsata’s place in Europe’s shared archaeological legacy.

Cover Image Credit: Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 4.0