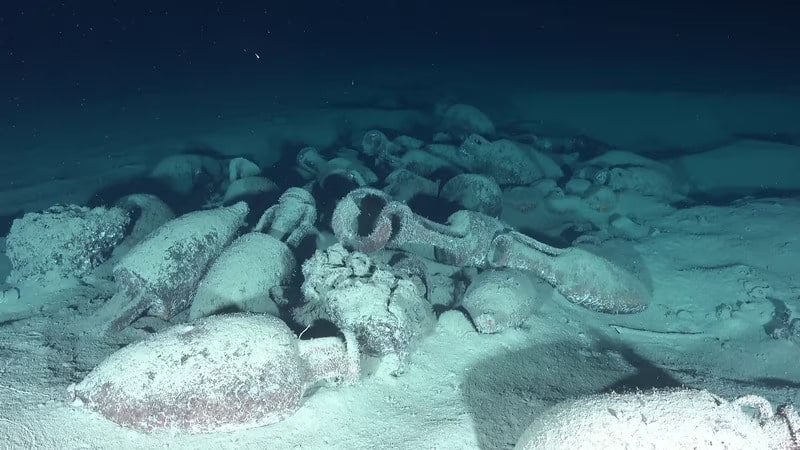

A team of archaeologists from eight countries—Algeria, Croatia, Egypt, France, Italy, Morocco, Spain, and Tunisia bordering the Mediterranean Sea has come together to scrutinize shipwrecks sitting at the bottom of the water body sitting between them. The researchers, coordinated by UNESCO, found three new shipwrecks.

In the largest and most ambitious international mission ever conducted, experts mapped an area of seabed 10km square in an effort to study and protect their shared underwater cultural heritage.

The remains of six shipwrecks from antiquity to the 20th century were documented using two robots and multibeam sonar. Three of the shipwrecks were previously unknown.

One wreck dates to between 100 BCE and 200 CE and two date from around the turn of the 20th century. The researchers presented their findings today in a press conference at UNESCO headquarters in Paris.

Archaeologists specifically investigated the continental shelves off Tunisia and Sicily, as part of distinct projects led by Tunisia and Italy, respectively.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The newly discovered shipwrecks sit near Keith Reef, a particularly treacherous region of the Skerki Bank. Keith Reef makes it challenging for ships, both ancient and modern, to navigate at certain points where it almost touches the Mediterranean’s surface. The new research clearly shows that some ships were a failure.

The shallow reef is situated in one of the busiest maritime routes in the Mediterranean, which has been used for millennia. It’s no surprise that ships have sunk there, or that looters have found it to be a lucrative hunting ground.

“When we found the new ships it was a [feeling] of relief because of all the effort we have all put in and that there are still things to learn from such a heavily looted area and that there is still something to protect,” Alison Faynot, an archaeologist with UNESCO, told The National.

“Underwater heritage is very important. You think it is extremely protected and unreachable and yet it is quite fragile, and just a change in the environment or seabed can have a very dangerous impact on it.”

The investigation of Sicily followed the work of marine archaeologists Anna McCann and Robert Ballard, who between 1998 and 2000 discovered eight stranded wrecks on the Italian continental shelf.

Three Roman wrecks discovered on the Italian continental shelf during the Ballard-McCann expeditions from the 1980s to the 2000s were also documented in high-resolution images by Arthur, a robot weighing less than 80kg and capable of going 2,500 meters deep.

The mission’s goal was to delineate the precise zone in which many shipwrecks lie and to document as many artifacts as possible because such underwater heritage is vulnerable to exploitation, trawling and fishing, trafficking, and the effects of climate change.

“The mission was possible due to France giving us access to its ship and robots which can go really deep. The technology available made it possible for us to do this work,” Ms Faynot said.

The two robots took more than 20,000 images and recorded 400 hours of video.

The research vessel the Alfred Merlin, equipped with high-tech underwater imaging and mapping equipment, from which an international team discovered three new shipwrecks on the Skerki Bank. Photo: M Pradinaud