Amid the stony hills southwest of Madaba, archaeologists from the University of Copenhagen have uncovered one of Jordan’s most extensive megalithic landscapes — a 5,500-year-old ceremonial complex at Murayghat where over 95 dolmens, standing stones, and monumental enclosures reshape our understanding of how early societies coped with crisis and change.

A dolmen is a type of megalithic tomb made from large stone slabs, typically used for collective burials during the Early Bronze Age. But at Murayghat, these stone monuments tell a story that extends far beyond death — one about how communities reinvented ritual, identity, and social order after the collapse of the Chalcolithic world.

A Monumental Response to Collapse

Around 3700 BCE, the prosperous Chalcolithic culture of the southern Levant — known for its copper artifacts, shrines, and communal settlements — began to unravel. Climate fluctuations, reduced rainfall, and the breakdown of long-distance trade networks ushered in a time of uncertainty. In this vacuum, early Bronze Age groups turned toward the landscape itself as a canvas for renewal.

“Murayghat gives us fascinating insight into how people responded to social and environmental stress by transforming nature into culture,” says project leader Prof. Susanne Kerner from the University of Copenhagen. “They built monuments to redefine community and belonging when traditional structures no longer worked.”

The Dolmen Fields of Murayghat

The Murayghat plateau is strewn with dolmen fields stretching across terraced hills overlooking Wadi Zerqa Main. Early surveys in the 19th century recorded as many as 150 dolmens, though modern excavations confirm 95 well-documented examples, with over 70 mapped in detail.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

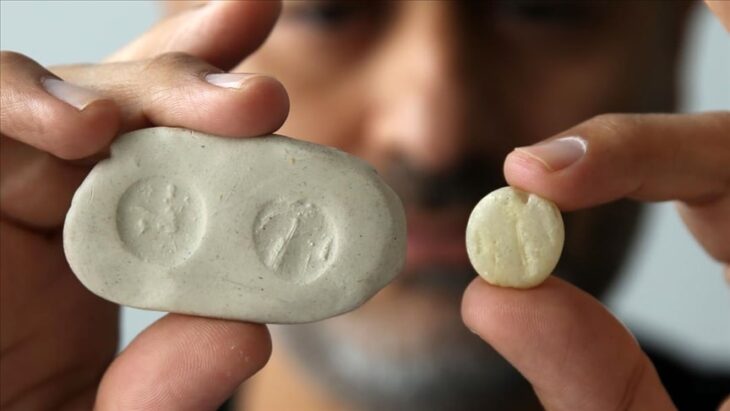

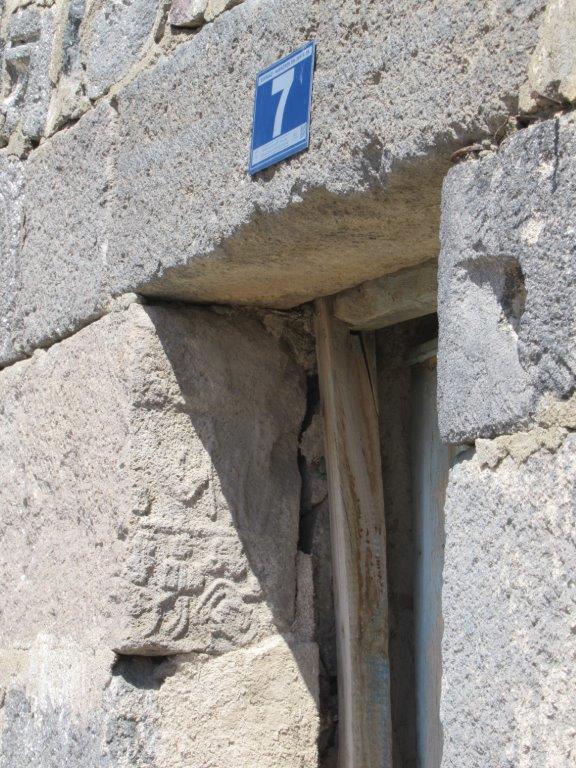

The dolmens vary in size from 2 to 4.5 meters in length and are built from thick limestone slabs that break naturally into roofing shapes. Many were once capped with triangular stones or encircled by stone rings and low tumuli. Though time, earthquakes, and quarrying have reduced many to collapsed outlines, their placement along ridgelines and terraces remains deliberate — each oriented toward a central hilltop enclosure that once served as the ritual heart of the site.

Kerner’s team found that these dolmen clusters were carefully arranged along natural contour lines and in sight of the main ceremonial area. Some appear built on artificial platforms, suggesting processional or symbolic alignment. The central knoll itself is crowned with standing stones and megalithic walls, forming horseshoe-shaped and rectangular structures that appear to have hosted gatherings, offerings, or ancestral commemorations.

A Landscape of Ritual and Communication

Unlike domestic settlements, Murayghat lacks hearths, storage silos, or roofing remains. Instead, it contains large open enclosures, carved bedrock basins, and lines of upright stones — features more suited to communal ceremonies than habitation.

Excavations revealed massive basalt grinders, horn cores from goats and gazelles, fragments of copper tools, and pottery linked to Early Bronze Age IA traditions. Among these are enormous communal bowls — the so-called Murayghat bowls — each capable of holding over 25 liters, likely used in feasts honoring the dead or celebrating seasonal rites.

The site’s visibility from surrounding valleys and its proximity to dolmen fields indicate it was a shared ceremonial center for multiple communities — a place to negotiate identity, territory, and spiritual continuity during a time of instability.

From Death to Identity

Dolmens across the Levant — from Mount Nebo to Jebel Mutawwaq and Tall al-‘Umayri — served as visible symbols of ancestry and land ownership. Their construction required cooperation, engineering skill, and collective memory. At Murayghat, this visibility was key. The dolmens, standing stones, and carved rock features together created what archaeologists call an anthropogenic landscape — a transformed natural terrain that materialized social relationships and belief systems.

Kerner interprets this landscape as both necropolis and forum:

“Murayghat was likely a meeting place — where people buried their dead, but also where they gathered, discussed, and redefined their society in the absence of central authority.”

The dolmens thus represent more than burial sites; they were instruments of communication between the living and the dead, between neighboring groups, and between humans and the land itself.

A Window into Early Complexity

The Murayghat Project, ongoing since 2014 under the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, continues to reshape how archaeologists view the early Bronze Age in Jordan. It shows that megalithic architecture, once thought to be the work of nomadic groups, was instead integral to emerging communities experimenting with new social and ritual systems.

As the dust of the Chalcolithic faded, people of the Early Bronze Age did not retreat into silence — they built enduring monuments of stone, embedding memory, faith, and resilience into the landscape of Murayghat.

The research findings have been detailed by Prof. Susanne Kerner in her recent article “Dolmens, Standing Stones and Ritual in Murayghat,” published in the journal Levant (2025).

Cover Image Credit: Susanne Kerner, University of Copenhagen