A groundbreaking genomic study uncovers the true origins of China’s mysterious hanging coffins and reveals that the modern Bo people are direct descendants of their ancient builders.

For centuries, the wooden coffins suspended high on cliff faces across southern China have stirred awe, speculation, and mystery. Perched on vertical rock walls, hidden deep within misty river gorges or tucked into narrow caves, these “hanging coffins” represent one of Asia’s most striking and least understood mortuary traditions. Their builders vanished from the historical record centuries ago, leaving behind dramatic archaeological traces but few written clues. Now, a groundbreaking genomic study has illuminated the origins of this enigmatic custom—and revealed that the people behind it may not be lost after all.

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and international collaborators have published the first large-scale genomic analysis of individuals associated with the hanging coffin tradition. Their findings point to a direct genetic link between ancient coffin builders and the modern Bo people of Yunnan, a small community long rumored in folklore to descend from the creators of the cliffside burials. For the first time, DNA evidence confirms that this oral memory reflects genuine ancestral continuity.

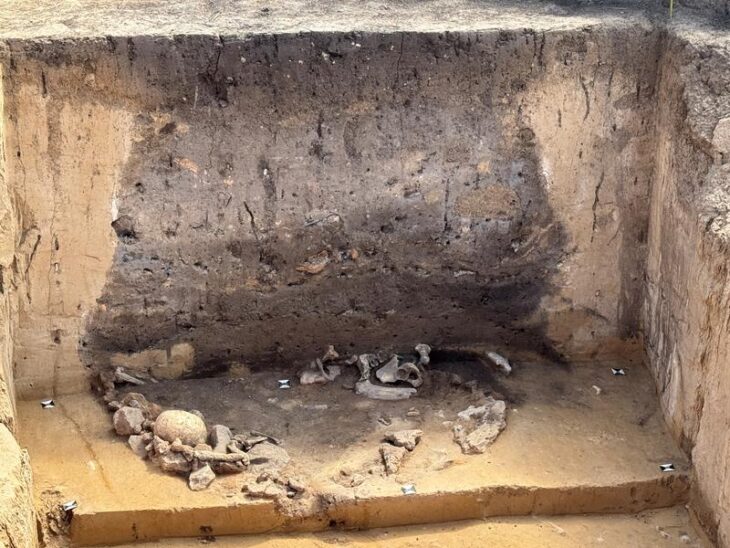

The study analyzed genomes from 11 ancient individuals recovered from hanging coffin sites in Yunnan and Guangxi, four individuals from log-coffin burials in northwestern Thailand, and 30 whole genomes from contemporary Bo villagers. Through comparative population genetics, the team uncovered a sweeping demographic story that stretches back thousands of years, tracing migration routes, cultural exchanges, and even unexpected long-distance interactions across East and Southeast Asia.

What emerges is a picture of deep-time movement and cultural resilience. The earliest origins of the hanging coffin custom, the researchers argue, lie among coastal Neolithic populations of southeastern China—communities ancestral to today’s Tai-Kadai and Austronesian language speakers. From roughly 3,000 years ago, this tradition spread inland along river corridors such as the Yangtze, eventually reaching the highlands of Yunnan and the rugged landscapes of northern Thailand. Despite occupying regions separated by mountains and thousands of kilometers, ancient coffin users across these sites share notable genetic and cultural threads.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The genetic signatures of the ancient Chinese hanging coffin individuals show strong affinities with the coastal Neolithic populations, but also reveal a patchwork of influences absorbed over centuries. Two Yunnan individuals, dated to around 1,200 years ago, displayed strikingly different ancestry profiles from their neighbors—one linked closely to ancient Yellow River farming groups and Himalayan Tibetans, the other aligned with populations from the Mongolian Plateau and Northeast Asia. Their presence suggests long-distance mobility and demographic contact during the Tang Dynasty, a period of profound interregional exchange. The researchers emphasize that such outliers highlight the cultural inclusivity of hanging coffin communities, which may have incorporated non-local individuals through migration or intermarriage.

Yet the most transformative finding emerges not from the ancient samples, but from the modern Bo villagers. Nestled in remote karst valleys of Yunnan, the Bo people number only a few thousand today. Officially classified under the broader Yi ethnic category, their language, traditions, and funerary customs have long set them apart. For generations, Bo oral history has insisted on an ancestral connection to the cliffside coffin builders, despite the lack of concrete historical documentation. The new genomic data provide conclusive support: most Bo individuals share their closest genetic affinity with ancient hanging coffin users from Yunnan. Modeling shows that nearly two-thirds of their ancestry derives from these ancient populations, with the remainder reflecting deeper Bronze Age mixing with other southwestern groups.

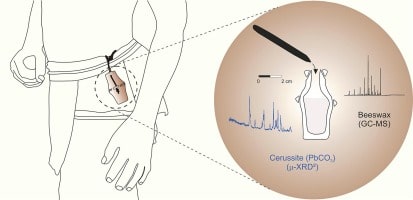

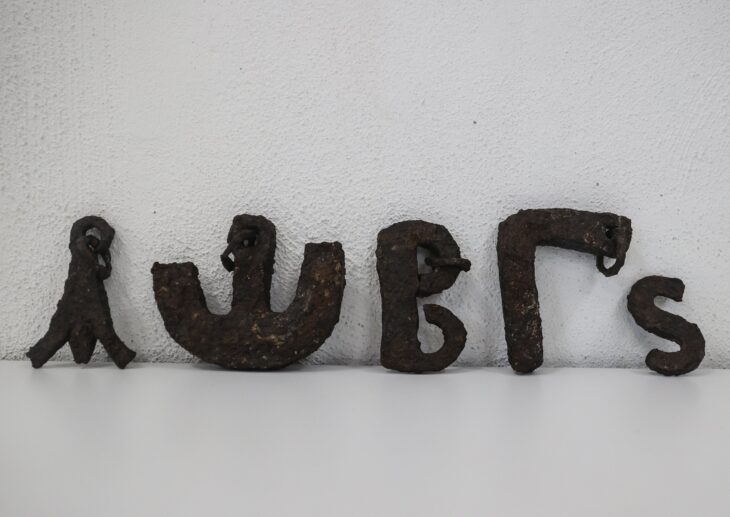

The study reveals that while the Bo people endured centuries of displacement, assimilation pressures, and even persecution during the Ming Dynasty, their genetic heritage remained remarkably persistent. Their distinct funerary tradition—known today as “soul cave burial,” in which the spiritual essence of the deceased is placed within ancestral caves—appears to be a cultural descendant of the ancient hanging coffin custom. Even the oxidation levels of copper pieces found in Bo ancestral caves suggest ritual continuity extending back more than 400 years.

Beyond China, the research also sheds light on the spread of log-coffin traditions into Thailand. Ancient individuals from Pang Mapha exhibit shared ancestry components with the Chinese sites, but also retain a stronger presence of Indigenous Hòabìnhian hunter-gatherer ancestry. The authors propose that this reflects local mixing between migrant groups from southern China and long-established Southeast Asian populations—a process possibly mediated by sex-biased interactions, in which male migrants intermarried with local women.

The study, while comprehensive, also highlights open questions. The earliest hanging coffin communities of the Wuyi Mountains—the region believed to be the cradle of the custom—remain genetically unsampled. Nor do archaeologists yet have DNA from related traditions in island Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Future excavation and genomic work will be essential to building a full picture of how this remarkable funerary practice spread and evolved.

For now, the genetic evidence offers a powerful new narrative. The hanging coffins of China, once seen as relics of a vanished people, can now be understood as part of a living cultural lineage. Their descendants, the Bo people, carry within their genomes a story of resilience across three millennia—a story of migration, adaptation, and the persistent human need to honor the dead in ways that touch the sky.

Zhou, H., Tao, L., Zhao, Y. et al. Exploration of hanging coffin customs and the Bo people in China through comparative genomics. Nat Commun 16, 10230 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65264-3

Cover Image Credit: Hanging coffins at Sagada, Mountain Province in the Philippines. Kok Leng, Maurice Yeo – Wikipedia